It’s Time to Wind Down the Student Loan Moratorium

The Biden administration recently extended the federal student loan moratorium through January 2022. Under the moratorium, most federal student loan borrowers do not need to make payments and interest does not accrue.

This policy was originally started in March 2020 to help borrowers with economic hardship as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. If it ends in January as scheduled, it will have lasted for 22 months and cost the federal government nearly $100 billion. While the moratorium has provided needed relief to some, it has disproportionately benefited highly-educated, high-income borrowers who have seen their wealth and incomes rise over the course of the pandemic.

In announcing the extension, the Department of Education said that it would be the last, and described January 31, 2022, as a “definitive end date”. Given the $4.3 billion monthly cost of continuing the policy, policymakers should keep to their word. While this expensive and regressive policy may have been justified in the depths of the pandemic, it no longer makes sense, particularly in comparison to other, better-targeted higher education reforms.

The Student Loan Payment Pause is Expensive

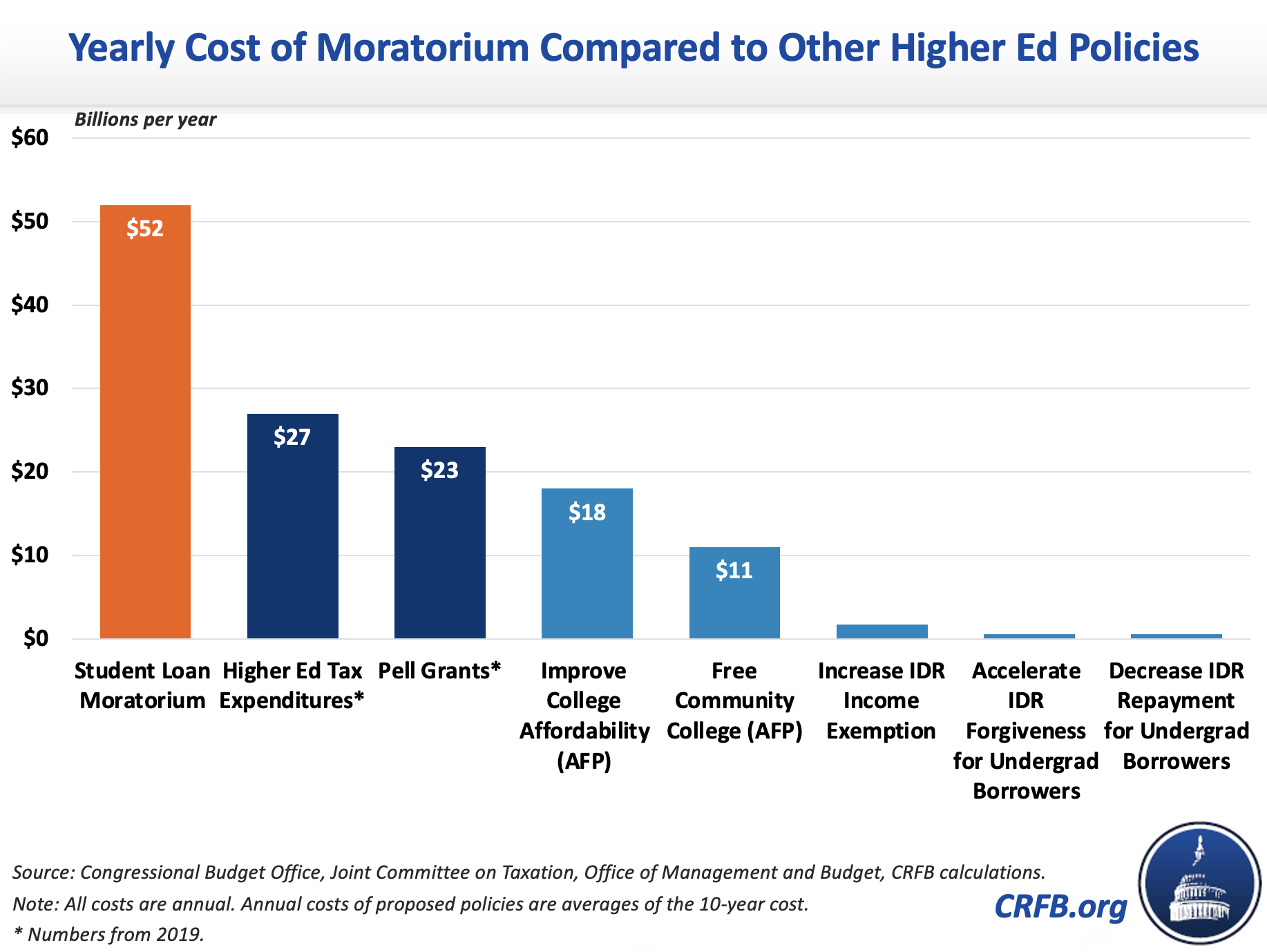

Before the pandemic, Americans were making roughly $7 billion per month in federal student loan payments. As a result of the payment moratorium, those numbers are way down, though it’s impossible to know exactly by how much due to a lack of data from the Department of Education. While some of those payments were simply deferred, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates suggest that the policy costs the federal government $4.3 billion for each month it’s in place – which is $52 billion per year and almost $100 billion over the length of the program.

For context, this $52 billion annual cost is more than the federal government spends on any other aspect of higher education each year. It’s more than double the $23 billion the federal government spent on Pell Grants in 2019 (before the pandemic). It’s also nearly twice as much as the $27 billion federal cost in 2019 of the main higher education tax expenditures, such as the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the student loan interest rate deduction.

The current student loan moratorium is also far more expensive than several, better-targeted alternatives to ease borrowers’ costs or make college more affordable. For example, the annual cost of extending the moratorium is about five times the total estimated cost of President Biden’s plan to provide free community college (the 22-month cost of the moratorium is similar to the community college plan cost over ten years). Continuing the moratorium would be three times more expensive than all of President Biden’s remaining higher education proposals in the American Families Plan, including his increase and expansion of Pell Grants, completion grants for community colleges, and grants for schools serving minority students.

Furthermore, the moratorium is about 88-times more expensive than it would be to reduce the cost of Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans by reducing the payment cap from 10 to 8 percent for new undergraduate borrowers, 85-times more expensive than accelerating the forgiveness period for new undergraduate borrowers by five years, and 30-times more expensive than increasing the income exemption from 150 to 175 percent of poverty for all new borrowers. These three IDR policies would help ease the repayment burden on borrowers who tend to struggle the most, while providing targeted cancellation rather than blanket deferral.[1]

Payment Pauses Are Regressive

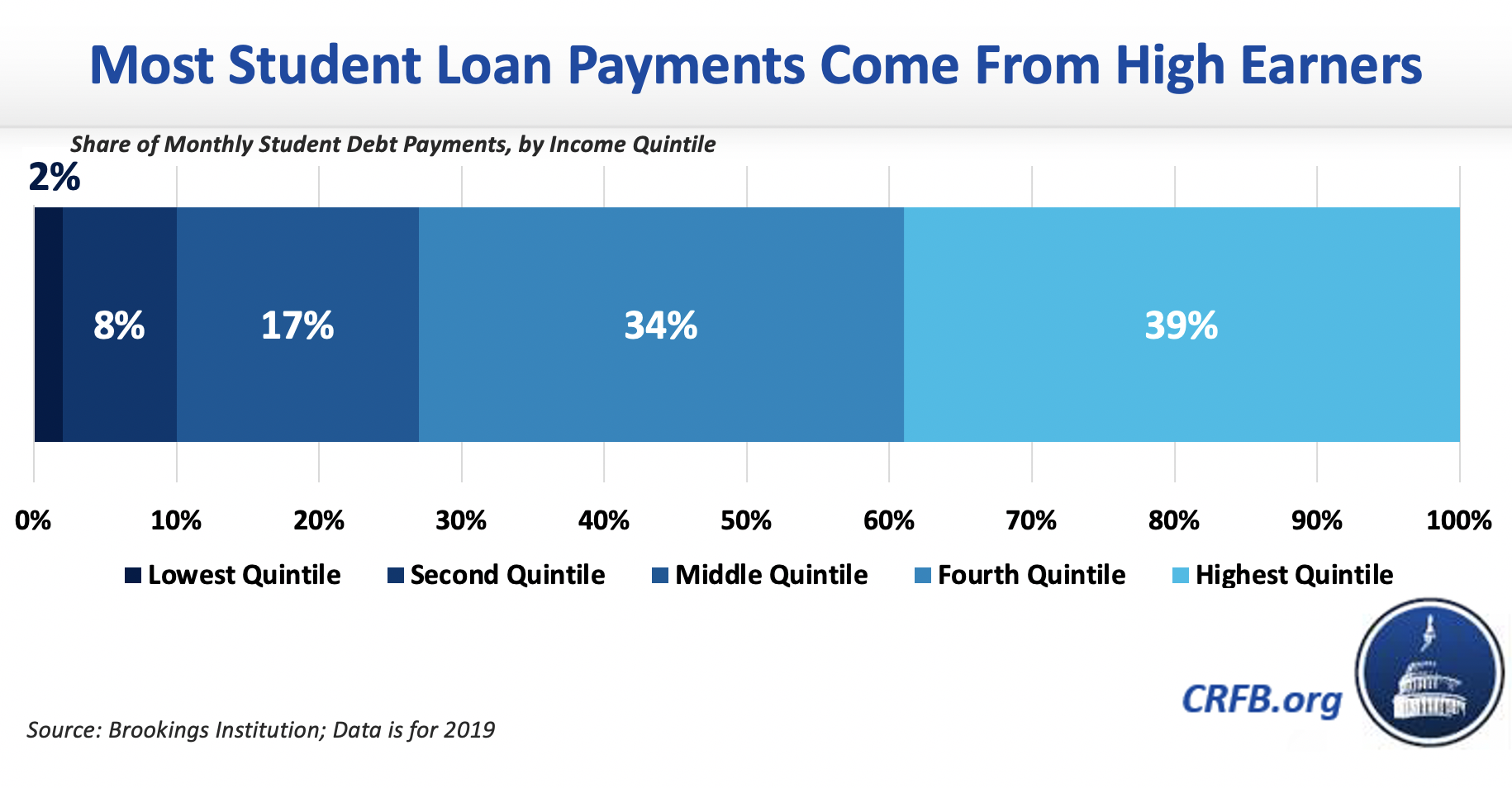

Not only is the student loan moratorium expensive, it is also regressive. Like blanket debt cancellation, it benefits those who borrowed more, and those who borrowed more tend to be more highly-educated and have higher incomes. They also are the least likely to have lost their job for an extended period of time during the pandemic. Almost 75 percent of repayment dollars are made by those in the top 40 percent of income earners, but the effects of the moratorium are likely even more skewed. Graduate student loans have higher interest rates than undergraduate loans, and so as a result, graduate students get more of a benefit dollar-for dollar-compared to undergraduate students.

A simple example demonstrates how regressive this policy is. Someone who borrows $10,000 at an interest rate of 4.5 percent will see their monthly payment of $100 paused, which means that month they will have $100 more dollars to use for other things, including possibly paying off others forms of debt like credits cards, which many Americans have been doing during the pandemic. Of that $100, $38 is interest that would have otherwise accrued but is instead forgiven, meaning that while their total loan balance stays the same; it crucially does not grow. Compare that with someone who borrowed $100,000 at an interest rate of 6 percent. The interest rate is higher because graduate student loans have higher interest rates. On a 10-year amortization schedule, this borrower owes around $1,100 a month, $500 of which is interest. That’s 13-times more interest forgiven per month. Importantly, that $1,100 of extra cash flow is significantly more than the $100 from the undergraduate borrower.

In the early parts of the pandemic, the federal government had little time or ability to target those most affected by the economic turmoil that ensued. Such poor targeting no longer makes sense, however, at this stage of the recovery.

* * *

The moratorium on student loan payments has provided important relief to nearly all student loan borrowers, but through January it will have cost the federal government roughly $100 billion. Continuing the policy will cost $4.3 billion per month and $52 billion per year. With most of these benefits accruing to high-income Americans, they will do little to boost economic activity, and it is not clear that these costs are justified at this point in the economic recovery. While Congress can and should pursue more targeted efforts to support borrowers and constrain college costs, it is time for the moratorium to end. New reforms should go through the normal legislative process subject to negotiation and be paid for through other offsets.

Between now and January 31, 2022, the Department of Education and its servicers should work hard to engage borrowers so they are prepared to resume repayments. The government should also inform struggling borrowers of the multitude of options available to them, including Income-Driven repayment plans as well as forbearance and deferment.

But the time has come to restart the repayment system.

[1] The costs of all referenced policy proposals are calculated by taking the average of the ten-year cost.