Inverting the Rewards of Inversions

Senators Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced legislation that would reduce the benefits to companies that choose to "invert," or move their headquarters overseas for tax reasons. The bill is very similar to a proposal included in last year's President's Budget, which would save about $3 billion over ten years by limiting tax deductions. It targets "earnings stripping," when companies with large amounts of cash borrow purely for tax reasons.

Recent months have seen a wave of corporate "tax inversions," where U.S. companies merge with a foreign corporation to move their headquarters overseas and avoid the high statutory U.S. tax rate on corporate income. Inversions are estimated to cost about $20 billion in lost corporate tax revenue over the next ten years.

Schumer and Durbin's proposal targets what they call “one of the most egregious practices of corporate inversions,” known as earnings stripping. This practice involves a foreign parent company lending to its U.S. subsidiary. Then, the U.S. subsidiary can send its profits to the parent company as interest. While this paper transaction doesn't change the company's overall financial position – it has the same income and debt levels as before – the loan provides two tax benefits. First, the U.S. subsidiary will have greater interest payments, which can be deducted as a business expense. Second, more of the company's income is "booked" outside the United States, where companies do not have to pay U.S. tax unless they repatriate the funds back to the U.S.

The proposal reduces the amount of interest payments that an inverted company can deduct (from 50 to 25 percent of taxable income), using an expanded definition of an inverted company (if the former shareholders of an inverted company own at least 50 percent of the foreign parent, decreased from 60 percent). It also requires inverted companies to get annual approval from the IRS for these subsidiary transactions they will claim on their tax returns. The bill applies to a company's future tax deductions – meaning it does not retroactively change taxes in past years – but it does not grandfather companies that have already inverted.

Schumer discussed the possibility of sunsetting his legislation in 2017, which would encourage Congress to reform the tax code before then. CRFB President Maya MacGuineas called for a similar approach: policymakers and businesses could agree to a 9-month strategic pause in inversions, paired with a fast-track procedure for tax reform.

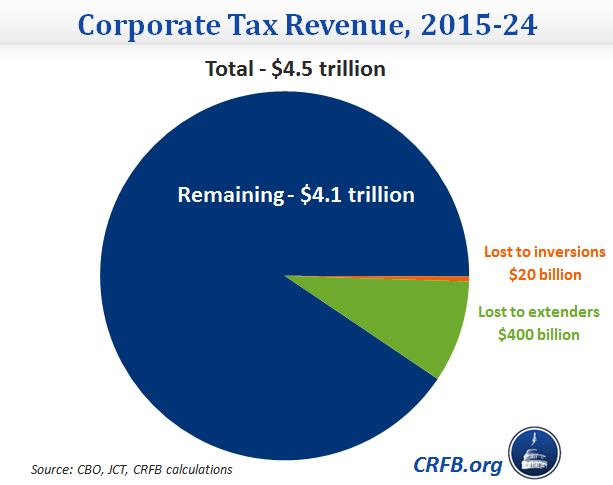

Although much has been made over the loss of corporate revenue resulting from inversions, it's important to put them in perspective. Inversions are estimated to cost about $20 billion over the next ten years. That's about half of one percent of the $4.5 trillion in expected corporate tax revenue. Further, we estimated that the tax extenders, a series of tax breaks that expired in 2013, would cost approximately $400 billion in lost corporate revenue if extended permanently. Unfortunately, both the House and Senate agree that these tax breaks should not be paid for when extended, causing 20 times the revenue loss of inversions.

The legislation proposed by Senators Schumer and Durbin is not the only one to tackle inversions. Senate Finance committee leaders Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) are working on a bipartisan bill, while Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew has indicated that he will act administratively if Congress does not act, announcing a decision "in the very near future." Among other things, administrative action could prevent earnings stripping from inverted companies by re-classifying debt as non-deductible equity.

Some lawmakers are proposing to pair the inversions legislation with legislation that would permanently extend some the tax breaks that expired last year. However, they should be wary of increasing deficits by pairing this legislation with a much costlier proposal.

Since our debt problems will eventually require more revenue, not less, policymakers will need to confront the long-term factors eroding the corporate tax base. Although restricting inversions can raise some revenue, MacGuineas said it best: "The best way to stop inversions is to enact comprehensive tax reform."

Use our interactive corporate tax reform calculator to see what a tax reform plan might look like.