Today marks the centennial anniversary of the federal income tax, signed into law on October 3, 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson. Though this date marks the beginning of the modern income tax, there were previous iterations of income taxes in the United States, one enacted during the Civil War (which expired in 1872) and another in 1894 (ruled unconstitutional the next year).

Prior to 1913, pressure was building for a federal income tax, particularly as the primary taxes in place in the late 19th century – tariffs and excise taxes – were seen as regressive and placed an unfair burden on the poor. The 1913 income tax was geared to raise revenue primarily from high-income individuals, and no one under the personal exemption amount of about $71,000 in 2013 dollars paid taxes. The income tax quickly changed, however, with the outbreak of World War I; tax rates rose and personal exemptions plummeted. But it was not until World War II that any substantial percentage of Americans paid the income tax.

Today, the income tax provides slightly less than half of all federal revenue, and is likely to remain one of the government's primary sources of income for the forseeable future. Over the years, the tax code has become increasingly riddled with provisions called tax expenditures, many of which we have been examining in our “Tax Break Down” series.

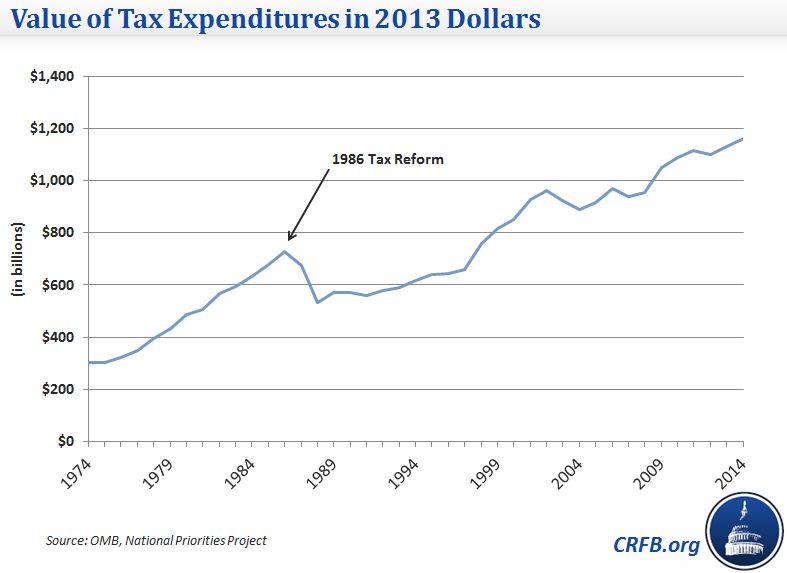

While many tax expenditures are popular (particularly to the people and industries they benefit), they will forgo nearly $1.3 trillion in revenue in 2013 (nearly as much money as the income tax raises) according to the Joint Committee on Taxation, and therefore require marginal tax rates to be much higher than they would otherwise be. Tax expenditures have grown from $303 billion in 1974 to over $1 trillion today (in constand 2013 dollars). There was a small dropoff after the Tax Reform Act of 1986, but it was short-lived.

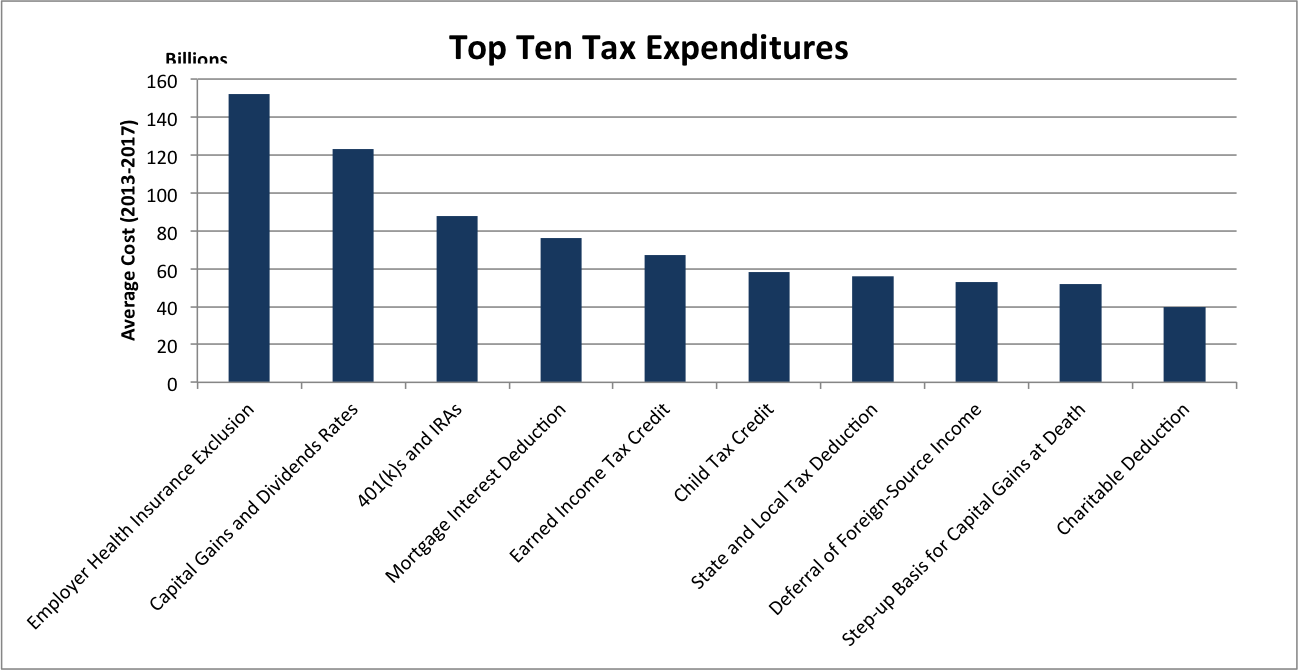

There are hundreds of tax breaks throughout the corporate and individual tax codes, but the most well-known provisions are also the most costly. The ten largest tax expenditures will cost a combined $718 billion in 2013, comprising more than half of the total cost of tax expenditures.

The sheer size of tax expenditures is a key reason why tax reform should be part of a comprehensive deal to put the budget on a sustainable path. Given that we are unlikely to solve our fiscal problems without additional revenues, lawmakers should look for ways to eliminate many of these tax expenditures to broaden the tax base, reduce rates, and reduce the deficit.

House Ways and Means Chairman David Camp (R-MI) and Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-MT) continue to push for tax reform this fall. Especially encouraging was the decision by Finance Chairman Baucus and Ranking Member Orrin Hatch to use a “

blank slate” similar to the Fiscal Commission’s “

zero plan,” which eliminates all tax expenditures and requires lawmakers to justify adding each one back into the code at the expense of higher marginal rates. There is no system in place to periodically review tax expenditures, and many have become entrenched without much scrutiny. As we show in our "

Tax Break-Down" series, many could also be redesigned to be less costly and more effective at promoting their goals. Lawmakers haven’t taken a hard look at the tax code in over 20 years.

On the 100th anniversary of the income tax, maybe it’s time for a facelift.