How Much Could Build Back Better Add to the Debt, An Update

Note: with recent Administrative actions on SNAP, debt-to-GDP will be about 0.6 percent higher in all scenarios. As a result, it will now reach 107 percent of GDP under current law, 120 percent under Build Back Better with extensions, and 130 percent of GDP under a current policy scenario that includes Build Back Better and extensions.

Now that the Senate has passed its bipartisan infrastructure bill and a Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 budget resolution, we have more information on the potential net cost of the "Build Back Better" agenda. This piece is an update to our August 3 analysis and reflects the actual cost of the infrastructure bill and the borrowing allowed under the Senate's reconciliation instructions.

Overall, we estimate these packages could cost as much as $2.4 trillion over ten years and set the stage for up to $4.3 trillion of total borrowing over the next decade. This cost would lift debt to 119 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2031, compared to a record 106.4 percent of GDP projected under current law. If lawmakers also extend the 2017 tax cuts (and other expiring provisions) and grow discretionary spending with the economy instead of inflation, debt could reach 129 percent of GDP by 2031. In that scenario, deficits could rise to nearly 9 percent of GDP and interest costs alone could reach or exceed the previous record of 3.2 percent of GDP set in 1991.

It's commendable that policymakers have called for fully offsetting new spending and tax breaks (see our five reasons to pay for investments). But the legislation and budget that passed the Senate would allow for massive new borrowing. Rather than rely on gimmicks and sleights of hand to achieve this, they should either scale back the proposals, identify the necessary tax increases and spending reductions to cover the full costs of their proposals, or both.

How Much Would Build Back Better Add to the Deficit?

The Build Back Better agenda consists of two parts: the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and a plan to use reconciliation instructions to enact $3.5 trillion of spending and tax breaks, mostly related to family benefits, health care, and climate change mitigation. The bipartisan infrastructure bill, which recently passed the Senate, will cost about $400 billion over ten years, based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates (this includes indirect increases in highway spending beyond the five-year highway bill). Meanwhile, the Senate budget resolution's reconciliation instructions allow for a maximum combined deficit increase of nearly $1.75 trillion over ten years – though lawmakers could borrow less. If these plans were both enacted with the maximum allowed borrowing, it would cost about $2.4 trillion over ten years, inclusive of $380 billion in interest costs.

In addition, drafters of the budget resolution have indicated that they intend to rely on arbitrary "sunsets" – where portions expire for no policy-based reason – within reconciliation legislation to fit $5.0 trillion to $5.5 trillion worth of policies into a $3.5 trillion framework.1 Assuming they don't scale back the policies they intend to pursue, future extensions could cost another $1.9 trillion with interest. In total, we estimate Build Back Better could ultimately set the stage for as much as $4.3 trillion of more debt over the next decade.

Total Potential Net Cost of Build Back Better Agenda

| Ten-Year Cost | |

|---|---|

| Net cost of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act | $400 billion |

| Allowed borrowing from reconciliation package | $1,750 billion |

| Potential cost of reconciliation package extensions | $1,750 billion* |

| Debt service costs | $380 billion |

| Total potential net costs of Build Back Better | $4,280 billion |

Source: CRFB estimates based on CBO and OMB data, rounded to the nearest $5 billion. *Assumes total cost of reconciliation policies, if made permanent, of $5.25 trillion – halfway between our published range of $5 trillion to $5.5 trillion.

For reference, this cost is about 65 percent larger than the total cost of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, if extended, over the same period (2022-2031). The $4.3 trillion is on top of the already-enacted American Rescue Plan, which added $2.1 trillion to the debt from 2021 through 2031.

How Much Would Build Back Better Boost the Debt?

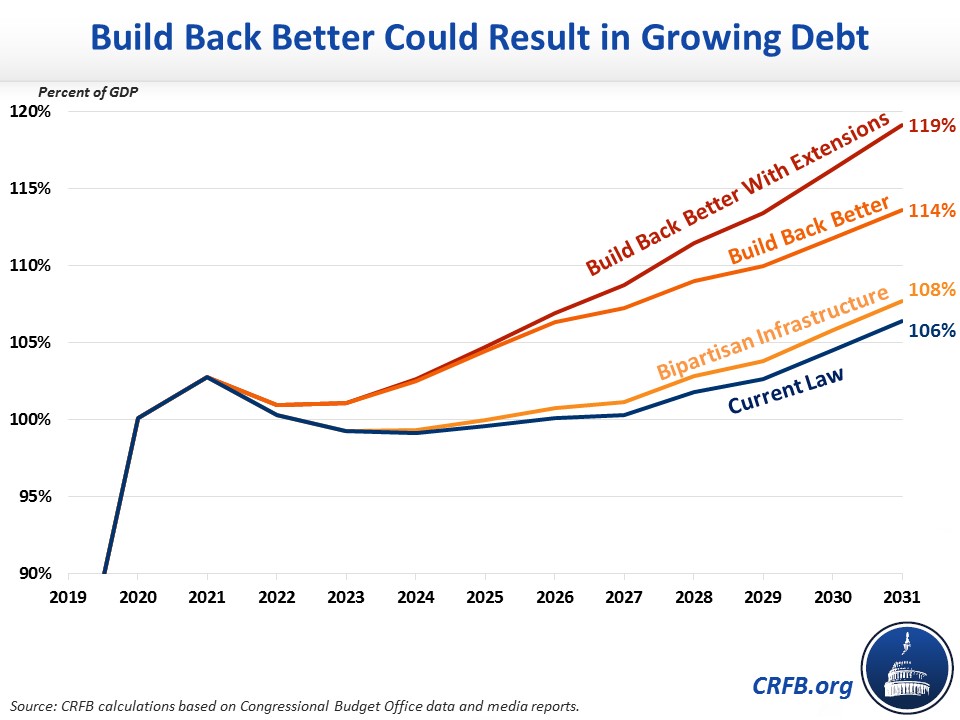

Under current law, debt is already slated to reach a new record – 106.4 percent of GDP – by 2031. Under Build Back Better, it would hit that record sooner and grow much faster.

With the enactment of the bipartisan infrastructure bill, debt would reach 108 percent of GDP by 2031. If lawmakers also borrow the full $1.75 trillion allowed under reconciliation, we estimate debt would rise to 114 percent of GDP by 2031, reaching a new record in 2027. Further incorporating possible extensions of expiring provisions, debt would rise to 119 percent of GDP by 2031.

How High Might Debt Go?

Unless policymakers ensure reconciliation legislation is actually fully paid for and abandon their plan to rely on arbitrary sunsets, the Build Back Better plan could set the stage for adding an additional 13 percent of GDP to the debt by the end of the decade. And there are risks that policymakers will make the situation far worse.

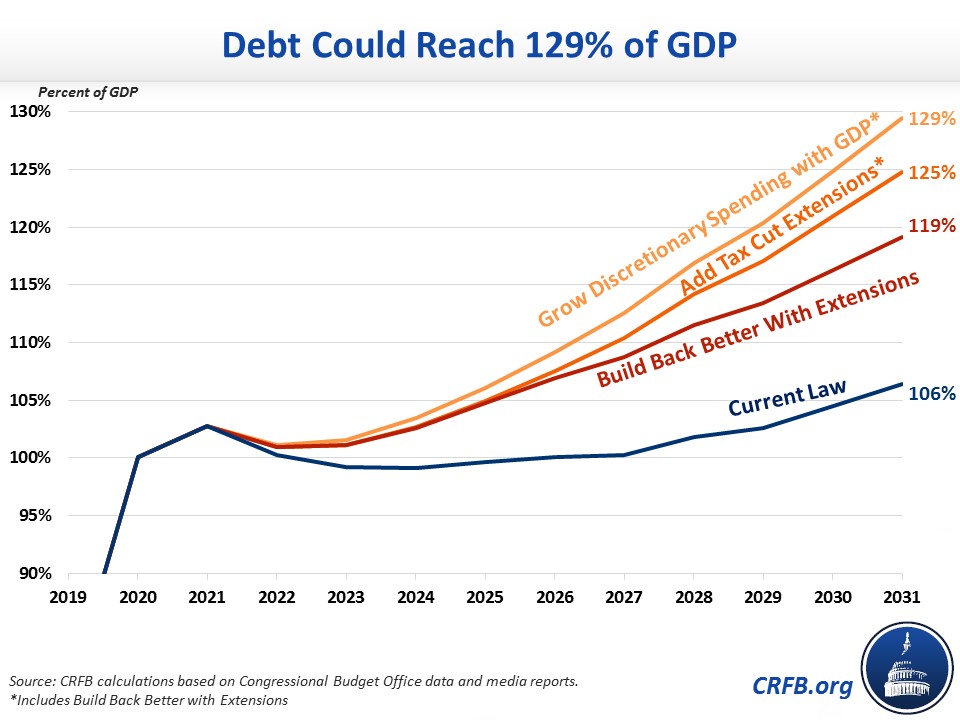

For example, if policymakers also extend various expiring tax provisions – mainly the expiration of individual provisions of the TCJA at the end of 2025 – debt would rise to 125 percent of GDP by the end of the decade. And if they grow appropriations with the economy rather than inflation, debt would reach 129 percent of GDP.2

In that scenario, debt would be increasing much more rapidly over the long term than under current law, growing by about 4 percent of GDP annually by the end of the decade rather than 1 to 2 percent under current law. The budget deficit in this scenario would be nearly 9 percent of GDP by 2031, with interest costs at or above the previous record of 3.2 percent of GDP set in 1991. In nominal dollars, we estimate the deficit could grow to roughly $3 trillion by 2031, of which nearly $1.1 trillion would be interest payments.

Importantly, none of these estimates incorporate economic feedback effects, which could improve or worsen the situation. For example, Build Back Better and extensions of the TCJA could boost revenue if it resulted in larger GDP but shrink revenue if new borrowing and taxes resulted in less output. In either case, the plans would almost certainly boost interest rates and debt service costs as a result of higher debt and increased labor productivity. Based on a recent CBO paper, we estimate the infrastructure bill will be roughly $10 billion (3 percent) cheaper over a decade when incorporating dynamic feedback – not nearly enough to offset a substantial portion of its cost.

*****

While no reconciliation bill has yet been written, the Senate budget resolution would allow for up to $1.75 trillion of borrowing on top of the $400 billion infrastructure bill. Including interest, the Build Back Better agenda could add about $2.4 trillion to the debt by 2031. Given the intention to allow various policies to expire, it would ultimately set the stage for $4.3 trillion of additional borrowing, causing debt to rise to 119 percent of GDP by 2031. Extending other temporary tax cuts and increasing discretionary spending with GDP would cause debt to reach 129 percent of GDP by 2031.

These numbers show that policymakers need to either reduce the gross cost of the infrastructure bill and reconciliation plan, incorporate additional offsets, or both to ensure a fiscally responsible plan. And going forward, policymakers should avoid enacting or extending other tax cuts and spending increases without fully offsetting the cost. Even under current law, debt is headed toward record levels. If policymakers abandon pay-as-you-go budgeting, the nation's debt trajectory would rise much more rapidly.

See the original version of this analysis here.

Read more options and analyses on our Reconciliation Resources page.

1 The final budget resolution appears to be even more expansive than what we assumed in our $5.5 trillion estimate, including policies such as a reduction in the Medicare age that were absent from our analysis. However, we continue to assume $5.25 trillion of total costs with extensions under the assumption that some policies are scaled down in size.

2 For Build Back Better, we use CBO's estimate of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which includes $550 billion of front-loaded costs with $200 billion of offsets, and assume the reconciliation plan increases deficits by $1.75 trillion in a frontloaded manner. We assume extensions of the reconciliation plan will cost roughly $1.75 trillion over a decade, bringing total costs to $3.9 trillion before interest. For tax extensions, we assume all individual and estate tax provisions from the TCJA will be extended, except for the top rate (which we assume will remain 39.6 percent) and the limit on pass-through loss deductions (which we assume is already enacted in the reconciliation plan); we also assume the extension of 100 percent bonus depreciation and various tax extenders not related to renewable energy at a combined cost of roughly $250 billion. For discretionary spending, we assume annual appropriations will grow with potential nominal GDP rather than with inflation, at a cost of roughly $1.4 trillion before interest.