The High Cost of Borrowing at Low Rates

Federal interest spending is on track to nearly double between 2020 and 2023 and projected to double again by 2032, due to rising interest rates and a growing national debt.

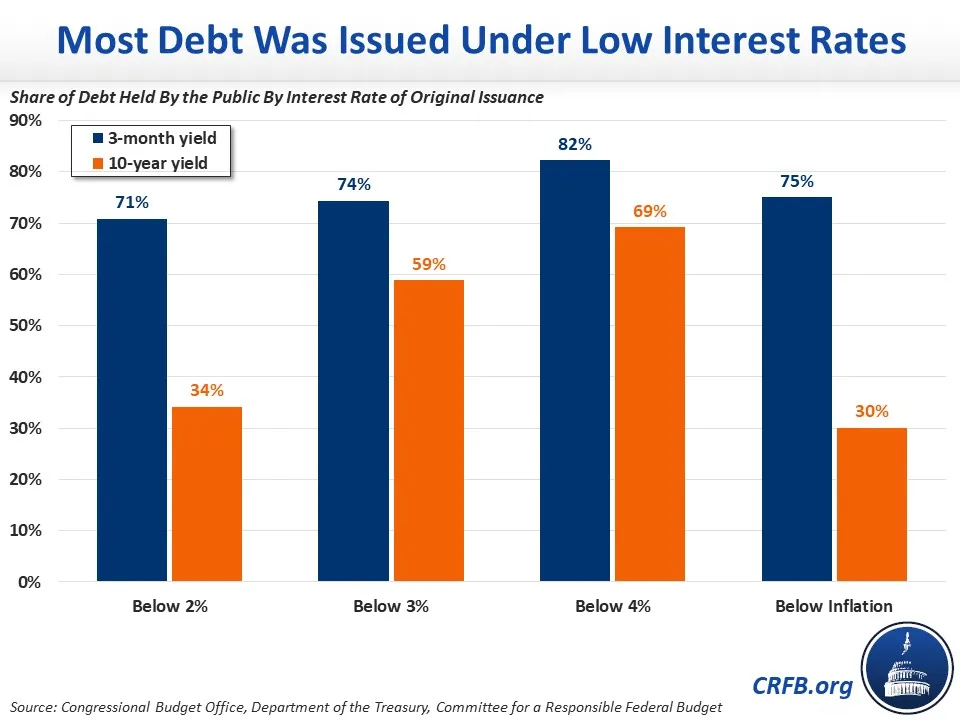

While commentators are increasingly recognizing the dangers of exploding interest costs, many fail to note that most of the costs resulted from borrowing when interest rates were low. We estimate that nearly 60 percent of our debt originated when the average interest rate on ten-year Treasury notes was less than 3 percent, while 75 percent of current debt originated when three-month Treasuries paid less than 3 percent.

That debt, borrowed at low rates, is now being rolled over into Treasuries paying interest rates between 4.5 and 5.6 percent. Though borrowing seemed cheap during those periods, policymakers failed to account for rollover risk, and we are now facing the cost.

The economy is coming out of a long period of low interest rates, beginning with the 2007-2009 global financial crisis when ten-year yields fell below 4 percent and continuing through the COVID-19 economic crisis, when the ten-year Treasury rate fell below 1 percent for almost a year.

During that period, economists, commentators, and politicians from across the political spectrum argued that low rates made it a "time to borrow." Paul Krugman, for example, argued in 2016 to “borrow money at these low, low rates and do some much-needed repair and renovation.” In 2020, when interest rates reached a low during the coronavirus pandemic, then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said, “one of the reasons I do feel comfortable with us spending all this money is because interest rates are very low. And we’re taking advantage of long-term rates.”

While there was certainly a logic to borrowing while interest rates were low, we warned at the time that this tactic would only work if there were a plan to pay back the debt before interest rates rose. Absent such a plan, low-rate debt would inevitably roll over to high-rate debt. Unfortunately, policymakers took to heart the idea of borrowing while rates were low without considering the rollover risk.

Of the $26 trillion of current debt held by the public:

- $21 trillion (80 percent) was originally borrowed when ten-year yields were below 4 percent

- $15 trillion (60 percent) was originally borrowed when ten-year yields were below 3 percent

- $7.4 trillion (30 percent) was originally borrowed when ten-year yields were below inflation

- $18 trillion (70 percent) was originally borrowed when three-month yields were below 2 percent

- $20 trillion (75 percent) was originally borrowed when three-month yields were below inflation

- $18 trillion (70 percent) was originally borrowed between 2008 and 2022, when ten-year rates averaged 2.4 percent and three-month rates averaged 0.5 percent

Currently, newly-issued ten-year Treasury bonds cost the government 4.5 percent per year and three-month Treasury bonds cost 5.6 percent, while the economy is expected to grow about 3.8 percent per year, nominally, over the long term. With more than half of all debt maturing in the next three years, this “cheap money” is becoming increasingly expensive.

Interest is currently the fastest growing part of the budget, and if current interest rates persist, interest costs could exceed defense spending within two years. They could hit a new record as a share of the economy as soon as 2026. And they could become the single largest government program in just two decades. Interest could total more than $12 trillion over the next decade. 1

While it is less costly to borrow when interest rates are low than when they are high, borrowing is never free and is rarely cheap. Policymakers should work to put the debt on a downward path, not only to help reduce interest rates, but also to reduce the fiscal and economic cost of high and rising debt.