Everything You Need to Know About Budget Gimmicks, in 8 Charts

Last week's report by the Congressional Budget Office showed that our debt remains on an unsustainable path, (see our ongoing blog series) and is projected to be $1.7 trillion higher by 2024 than we previously thought.

Despite the dismal fiscal picture, Congress may be considering measures to worsen the deficit, and covering their tracks with so-called "budget gimmicks."

Today, we released a chartbook, "Avoiding Budget Gimmicks," which explains and illustrates several of the tricks and slights of hand that policymakers may use to avoid identifying genuine offsets and payfors.

Today, we released a chartbook, "Avoiding Budget Gimmicks," which explains and illustrates several of the tricks and slights of hand that policymakers may use to avoid identifying genuine offsets and payfors.

We encourage our readers to share these charts and graphs and to hold policymakers accountable for efforts to worsen the long-term fiscal situation.

A pdf version of this chartbook is available here. The individual charts, with descriptions, are also posted below.

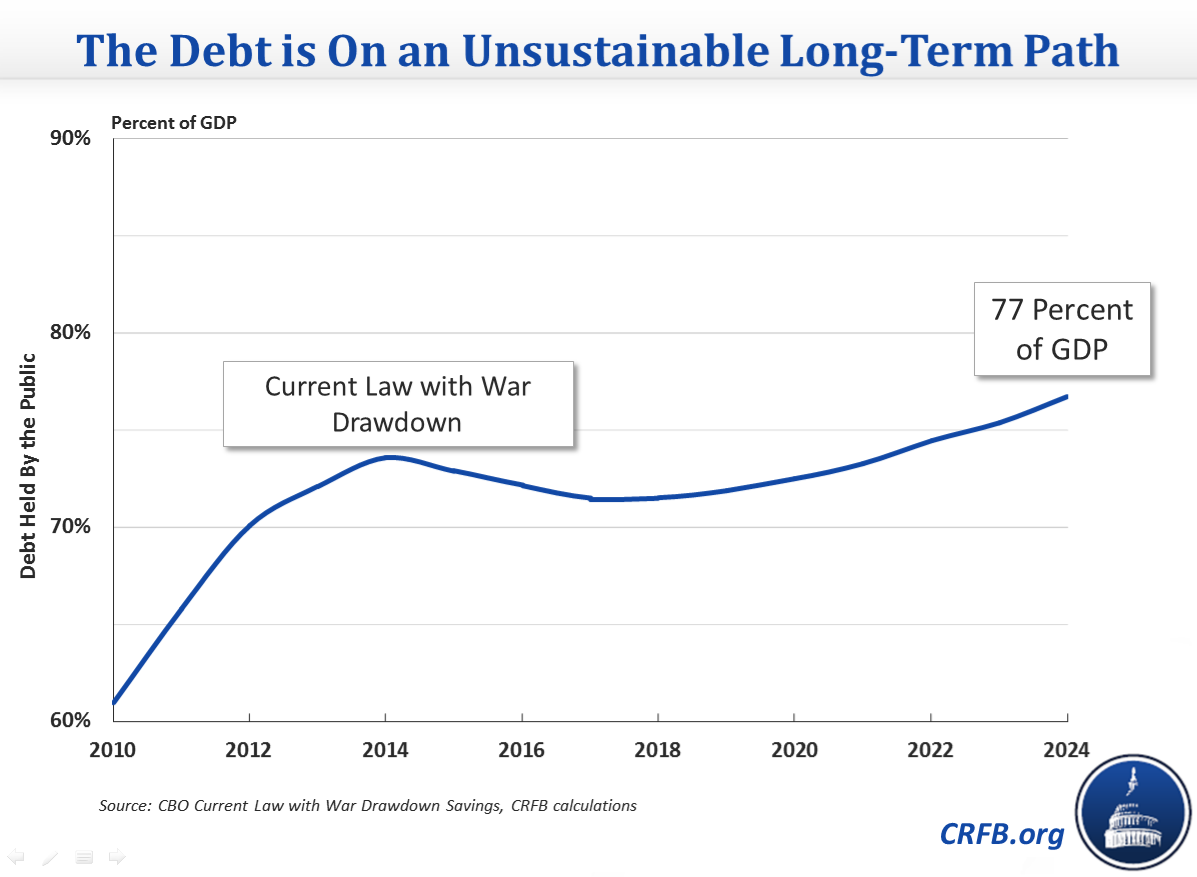

Chart 1: The National Debt is High and Growing

Debt is currently at its highest level since World War II, and is expected to continue to grow later this decade. Assuming the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan continue to unwind and policymakers abide by current law, debt is projected to rise from 72 percent of GDP in 2013 to 77 percent by 2024.

Chart 2: Deficit-Financed Extensions Would Make the Debt Much Worse

While abiding by current law will allow debt to grow to 77 percent of GDP, continuing expiring (or expired) provisions without legitimate offsets could make the situation far worse. Extending the current doc fix, the recently expired tax extenders, and certain refundable tax credits would increase debt levels to 80 percent of GDP by 2024. Adding a repeal of future sequestration cuts would increase it to 84 percent. Additionally reinstating and extending unemployment benefits and "bonus depreciation" could drive the debt to 86 percent of GDP.

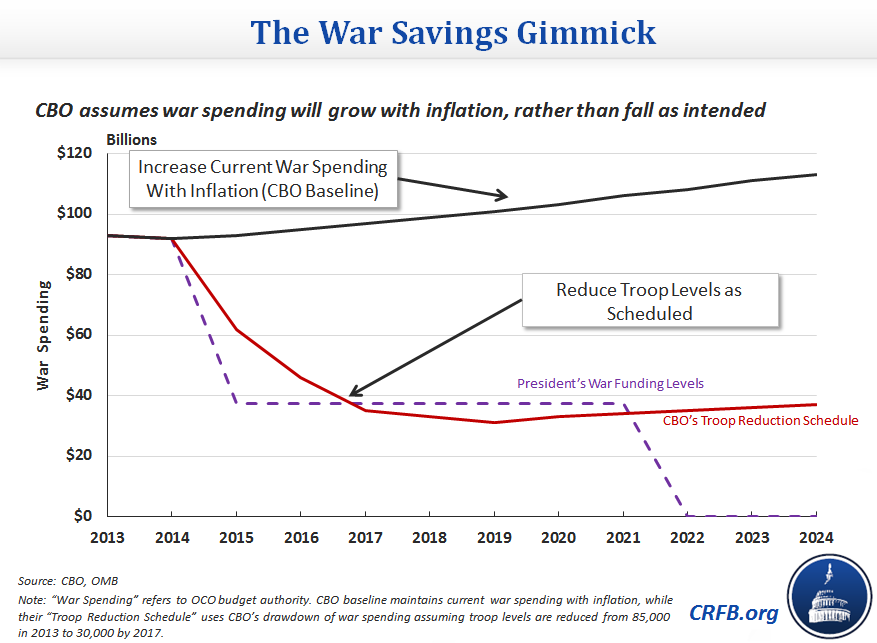

Chart 3: The War Gimmick May Allow Policymakers to Avoid Tough Choices

Under current budget conventions, uncapped discretionary spending, like war spending, is assumed to grow with inflation in the CBO baseline regardless of future plans. Some have suggested taking advantage of this quirk to cap war spending below the CBO baseline but well above the levels consistent with the drawdown currently underway. Yet capping spending above what current policy dictates and what Congress intends to spend will not result in lower future spending, and will generate only phantom savings.

The Congressional Budget Office, as well as budget experts on the left and right, all warn that war savings are illusory:

Chart 4: Using the War Gimmick Can Create a Slush Fund to Further Worsen the Debt

If war spending is capped at levels in excess of expected costs, these caps will create a slush fund for future spending. Specifically, lawmakers could further lower the caps to offset new priorities, or could sneak normal defense costs under the war spending caps if they are still elevated above drawdown levels. For example, if lawmakers set war spending caps $50 billion (over ten years) below the CBO baseline, it would create a $600 billion slush fund to avoid paying for future initiatives.

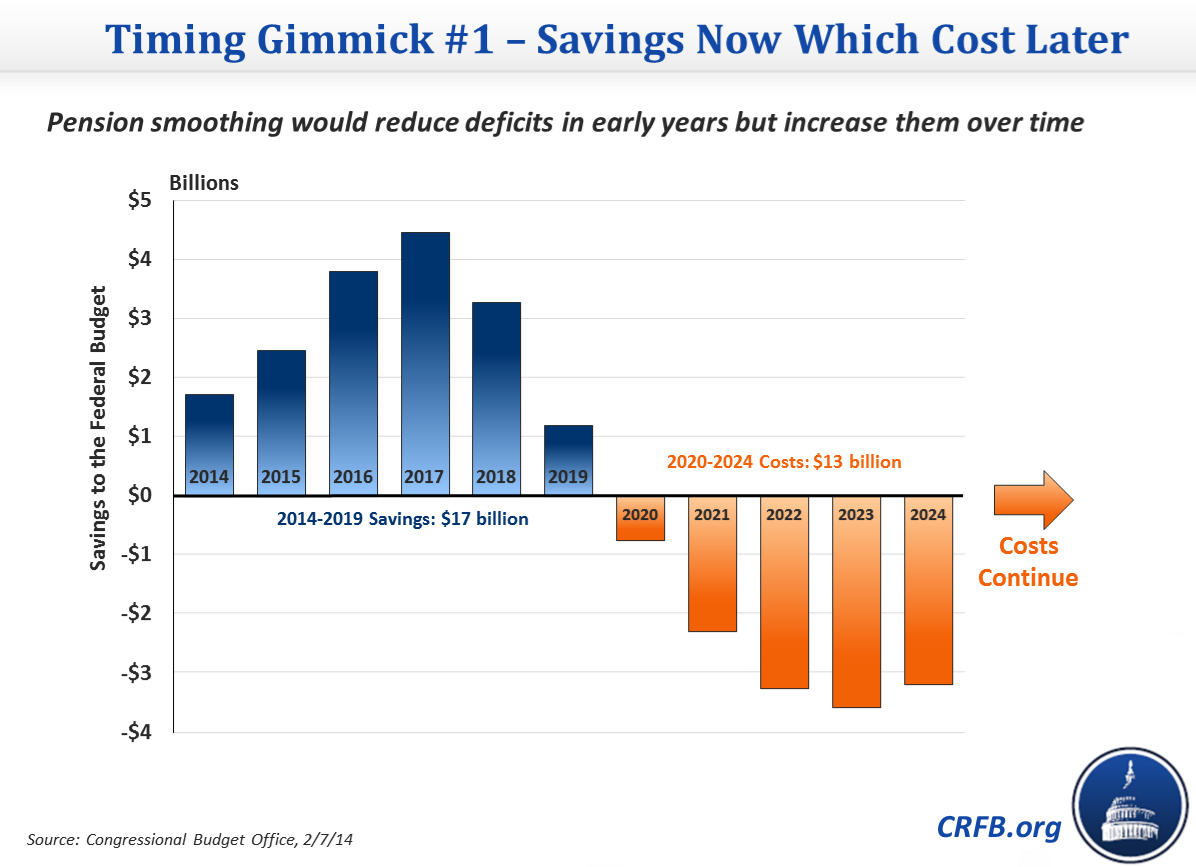

Chart 5: Policies Which Save Now and Cost Later Don't Really Save At All

Some policies take advantage of the ten-year budget window by taking credit for alleged savings that only represent a timing shift. For instance, a provision called pension smoothing would increase tax revenues in the first six years, but lose revenue beyond that and have no significant budgetary impact over the long-run.

Similarly, budget experts from across the political spectrum warn that this sort of timing shift is a gimmick:

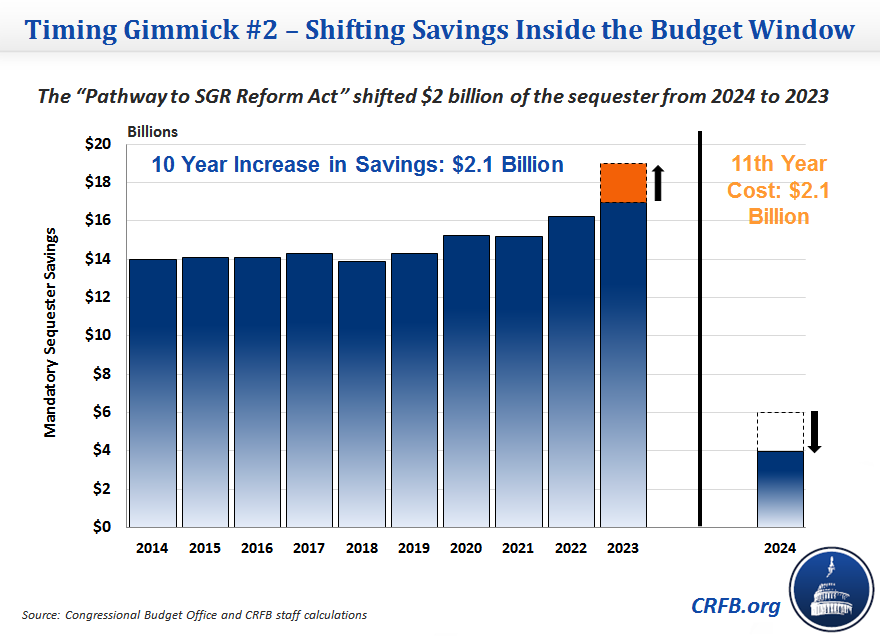

Chart 6: Moving Savings from Year 11 to Year 10 Doesn't Reduce the Deficit

Another timing gimmick takes savings which would have occurred in the 11th year – just outside the ten year budget window – and moves them into the 10th. This shift may appear to reduce ten-year deficits, but in fact results in no net savings. Policymakers used this gimmick when approving a 3-month "doc fix" in December 2013.

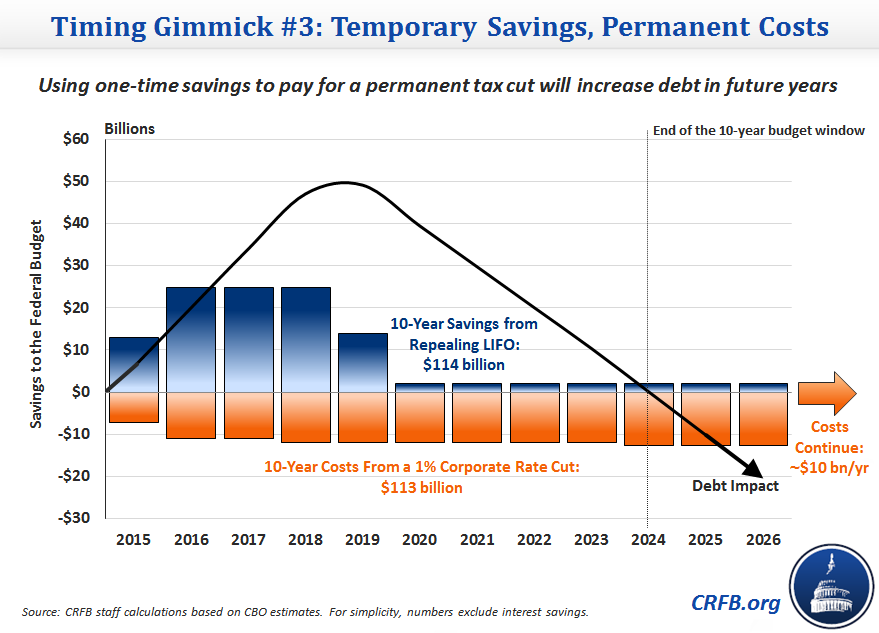

Chart 7: Offsetting Permanent Costs with Temporary Savings Results in Permanent Costs

Some policy changes have largely temporary deficit impacts, while others have largely permanent impacts. Using a temporary policy to pay for a permanent one may appear to add up over ten years, but would worsen the fiscal outlook over the long-run. For example, adopting LIFO accounting in the tax code would generate mostly temporary revenue; using that revenue to pay for a permanent rate reduction would increase long-term deficits and debt.

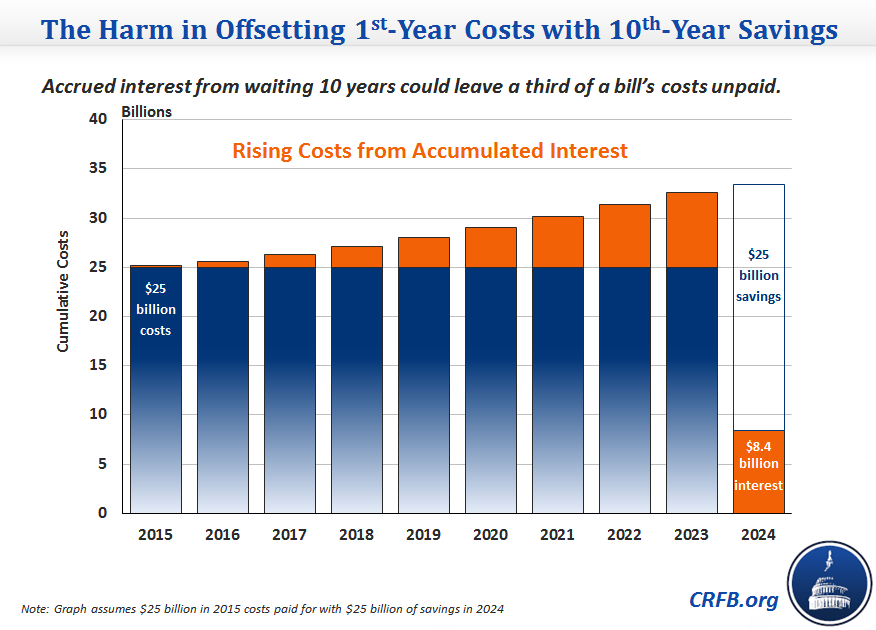

Chart 8: Waiting Ten Years to Start Paying May Be Unwise

Although it may not be considered a gimmick, waiting until the end of the decade to pay for new spending can be both risky and costly. First, an offset far in the future may not be viewed as credible. Even if it were, however, substantial interest costs would accrue over the decade. In the example below, waiting ten years to pay a $25 billion bill results in interest costs equal to one-third of the primary budget impact.

The long-term debt problem is daunting enough, and it will be worse if lawmakers continue to suggest using budget gimmicks to hide or obscure the costs of new policies. We encourage readers to use these tools to hold lawmakers accountable for their efforts to worsen the long-term fiscal situation. Our whole chartbook is available here, or as a printer-friendly PDF. You can read more detail about these and other gimmicks in our paper Beware of Budget Gimmicks.

The long-term debt problem is daunting enough, and it will be worse if lawmakers continue to suggest using budget gimmicks to hide or obscure the costs of new policies. We encourage readers to use these tools to hold lawmakers accountable for their efforts to worsen the long-term fiscal situation. Our whole chartbook is available here, or as a printer-friendly PDF. You can read more detail about these and other gimmicks in our paper Beware of Budget Gimmicks.

Related Blogs:

- Pension Gimmick Rises Again

- Sanders Bill Would Add to the Debt, Create a $250 Billion Slush Fund

- Gimmicks at Their Worst: The "War Savings" Gimmick

- Replacing the Sequester With...More Sequester? No Deal.

- Policymakers Must Not Double-Count Retirement Savings

Note: The last chart was updated on February 12 to include estimates from CBO's newest interest projections.

Tweet This Chart

Tweet This Chart