Delayed Action on Extenders Might Add to FY 2015 Deficit

While explaining why deficits have fallen from their historically large peak in 2009, we noted the main source of this tumble is a 43 percent rise in revenue. This increase came largely from the recovering economy, but also from legislated tax increases and the expiration of some temporary tax provisions. However, those provisions may be coming back soon and lead to a significantly greater increase in the deficit next year than projected under current law.

As CBO pointed out, the expiration of bonus depreciation played a large part in revenue increase:

Taxable profits were boosted in large part by the expiration at the end of December 2013 of various tax provisions, most significantly the rules that allowed firms with large amounts of investment to expense—that is, immediately deduct from taxable income—50 percent of their investment in equipment.

In our paper analyzing the Fiscal Year 2014 budget results, we pointed out that the decrease in the deficit was a temporary phenomenon and deficits would start increasing again after next year. If Congress were to extend expired tax breaks, it would both magnify the decline in the deficit in 2014 and prevent the deficit from declining in 2015.

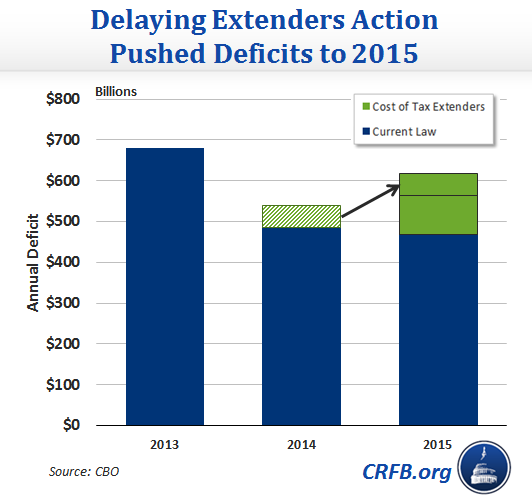

Since the 2014 fiscal year is over and these tax extenders have not been extended yet, the 2014 deficit would not change even if the provisions are made retroactive to the beginning of the year as planned. The revenue loss from the 2014 tax cuts will show up in 2015 when companies and individuals file their taxes for 2014 and have lower tax payments or receive refunds as a result of the retroactively extended tax breaks. The same thing happened with bonus depreciation in FY 2010, when it registered very little cost because it was not extended until near the end of the fiscal year. In either case, the federal government loses the full amount of revenue from the tax break, but in the following year.

In this case, the longer lawmakers delayed reviving the tax extenders, the more the 2014 cost was shifted into 2015. Last year, CBO estimated that extending all the tax extenders would cost $54 billion in 2014, but that dropped to $51 billion in the February estimate and $25 billion in the April estimate with the costs in 2015 increasing by a corresponding amount. Now, all of the $54 billion would show up in 2015, bringing the total 2015 cost of the extenders to $139 billion.

Of course, if Congress does not retroactively extend the expired tax breaks or chooses to allow some of them to expire, the Treasury won't experience this loss of revenues in 2015, and there might actually be an increase in revenues as corporations that assumed the tax breaks would be extended when making tax payments in 2014 would need to make higher tax payments when they file their 2014 taxes next year. If Congress wants to prevent the deficit from increasing greatly in 2015, allowing the extenders to expire or paying for their extension would be a good place to start. However, this seems unlikely given the bipartisan support for these tax breaks in Congress.

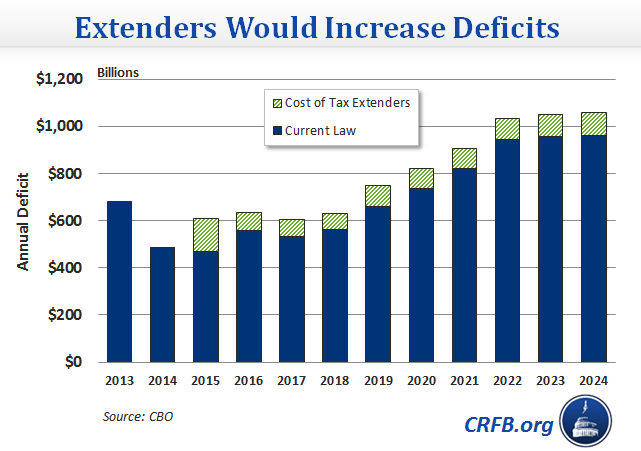

Not only would the deficit increase in 2015, but if lawmakers continually extend the tax breaks without offsetting savings, future deficits will be between $70 and $100 billion higher a year. The annual deficit would exceed $1 trillion by 2022, three years sooner than predicted under current law by CBO.

By delaying action on the extenders, lawmakers have already lowered the 2014 deficit. To prevent the 2015 deficit from rising significantly, they could offset the tax extenders or make the package much less expensive by only extending certain provisions. Dealing responsibly with these tax provisions would prevent hundreds of billions from being added to debt over the next ten years.