CFED: Housing Tax Incentives are Upside Down

Tax breaks for homeowners are one of the largest categories of tax breaks offered by the federal government. A new report by the Corporation for Enterprise Development entitled "Upside Down: Homeownership Tax Programs" quantifies these tax breaks, showing that the majority of federal housing resources are given through the tax code. Because of their structure, these tax breaks result in an outsized benefit for the wealthiest homeowners.

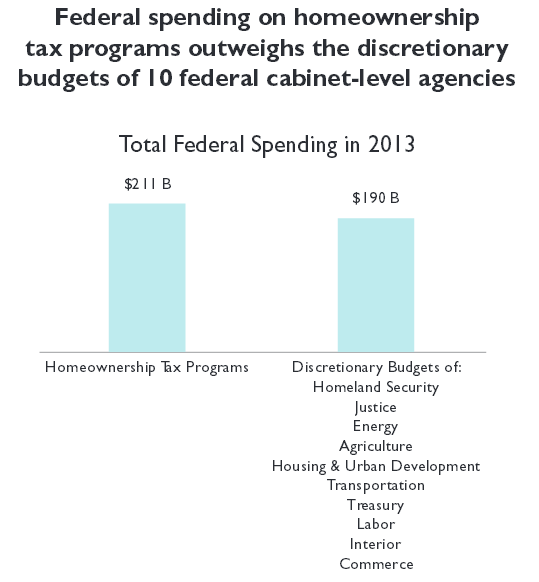

The report profiles seven tax breaks given to homeowners, totaling $221 billion in lost annual revenue for the government. This cost is not only larger than the budget for the Department of Housing and Urban Development, but also nine other Cabinet level agencies combined. Incentives to support homeownership are also much larger than those for affordable housing, such as the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.

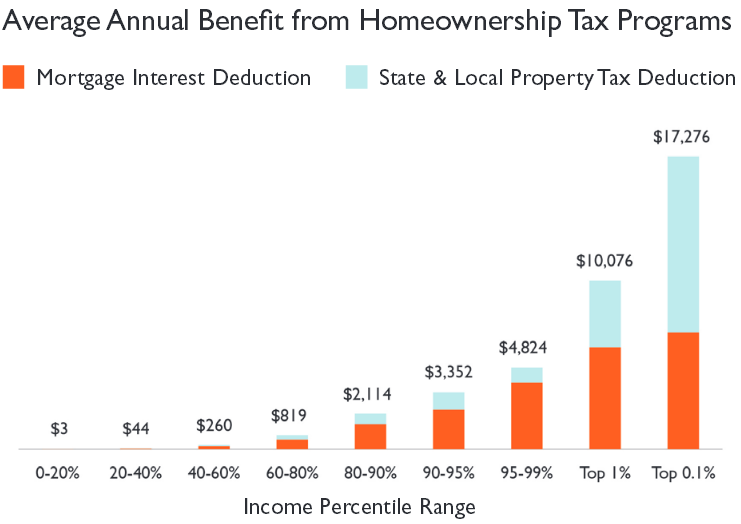

Two of the largest preferences highlighted in this report are the mortgage interest deduction, which cost the federal government $69 billion in 2013, and the property tax deduction, which cost $29 billion. Both deductions are only available if a taxpayer owns their home and itemizes their deductions, which means they aren't available to the more than two-thirds of taxpayers that do not itemize. Because wealthier individuals are more likely to itemize and face higher marginal tax rates, they gain a larger benefit from the deductions. The average family in the top 1 percent of the income distribution received over $10,000 in benefits from these two deductions, while the average family in the bottom fifth received $3. In particular, the benefits of the property tax deduction grow rapidly at the top of the income scale since it is not capped like the mortgage interest deduction.

The report also points out that the mortgage interest deduction subsidizes debt, not homeownership – it encourages the same family to buy bigger homes and take out bigger loans. In addition, the deduction is not well-timed to assist low-income families with the upfront costs to buying a home, since the tax benefits are spread out over the lifetime of the home loan.

With these problems in mind, the report proposed several solutions. First, the report calls to permanently reinstate the First-Time Homebuyer’s Tax Credit that was in effect between 2008-2011, arguing that it was the only "right-side up" incentive that focused its benefits on low- and middle-income households. The report would pair the credit with a tax-free savings plan to allow prospective first-time homeowners to save with matching contributions from the federal government.

In addition, the report would replace the current system of deductions with tax credits, which provides the same size benefit to households of every income level and can be made refundable. Both the Bowles-Simpson and Domenici-Rivlin plans made this recommendation, replacing the mortgage deduction with a credit.

Finally, the report would reduce subsidies for "excessive debt". One example would be House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp's (R-MI) Tax Reform Act of 2014, which would reduce the amount of debt eligible for the deduction from $1 million to $500,000.

The government's largest homeownership programs are tax incentives, rather than spending programs. As currently structured, these tax incentives offer the largest boost to wealthy homeowners and encourage greater indebtedness, rather than focusing on helping first-time homeowners who might otherwise struggle to afford a home. If policymakers decide to reform housing incentives to reduce their size or to better target them, they have plenty of options to consider. This report illustrates one way that reforming tax expenditures can be used to better achieve policy goals and better assist low- and middle-income taxpayers while simultaneously reducing the costs to the federal government and improving progressivity of the tax code.

Read the full report "Upside Down: Homeownership Tax Programs" here.

Related Posts: