4 Ideas That Should Be Considered For Any Health Reform Package

It is unclear whether the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) – the Senate GOP's proposal to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA or "Obamacare") – will pass the Senate in the coming weeks. Some have argued that it cuts Medicaid and other spending too deep, while others have argued that it does too little to reduce costs or repeal Obamacare – making the path to 50 votes a challenging one.

Yet regardless of what happens to the BCRA, federal and total health care spending is projected to grow at unsustainable rates, and future reforms to slow health care cost growth will surely be needed. These reforms will involve changes to Medicare and the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance. They will also involve changes to Medicaid and the exchange subsidies; in this space, the BCRA includes a number of thoughtful cost-control ideas, including:

- Limiting States' Ability to Use Provider Taxes to Inflate Reported Medicaid Costs

- Incentivizing States to Reevaluate Medicaid Eligibility More Frequently

- Further Means-Testing the Subsidy Schedule for the Individual Market

- Enacting a Per-Capita Cap on Medicaid Spending

These reforms merit serious debate and consideration.

Limiting States' Ability to Use Provider Taxes to Inflate Reported Medicaid Costs

Since Medicaid is a state-run but jointly-financed program, the best way to control its costs is to support and encourage states' cost-control efforts. The current matching rate already does this to some degree, since states typically get to keep an average of 40 cents for every dollar they save. Yet the current system also includes a number of loopholes that allow states to shift costs to the federal government by offering a misleading picture of their total spending.

Based on our recommendations, the BCRA includes a policy that modestly restrict state cost-shifting efforts. Specifically, it gradually reduces the provider taxes states can impose from 6 percent of net patient revenues to 5 percent.

As we've explained in detail previously, states can currently increase reported Medicaid costs by simultaneously increasing payments to providers and taxing those very same providers. In theory, the combination of higher payments and taxes will ensure the provider is no worse (or perhaps even better) off. But with higher reported outlays, state governments can collect a larger matching payment from the federal government. This is a clear gimmick that drives up costs and has little to no justification.

The BCRA very modestly pares back the limit on provider taxes from the current law 6 percent of net patient revenues to 5 percent by 2026. CBO estimates this measure alone would save about $5 billion over the next decade – a more immediate phasedown could save as much as $16 billion. This is a good start, but it doesn't go nearly far enough. In 2013, the Obama Administration proposed reducing the threshold to 3.5 percent, which would save over $50 billion. The bipartisan Simpson-Bowles plan proposed to gradually phase out the provider tax gimmick entirely, which could save over $100 billion.

Incentivizing States to Reevaluate Medicaid Eligibility More Frequently

The BCRA, similar to the House-passed American Health Care Act (AHCA) before it, includes a provision to incentivize states to redetermine eligibility for Medicaid more frequently than they do today. Under current law, states are required to redetermine eligibility at least annually, though some states choose to redetermine eligibility more frequently. Because Medicaid has certain eligibility requirements that vary by state but include things such as income limits, asset limits, and other requirements, determining eligibility only once per year allows some individuals who would no longer qualify for Medicaid to continue receiving benefits.

The BCRA would allow states to increase redetermination to every six months or more frequently, with additional funding incentives to do so. Although CBO hasn't directly scored this provision because it would interact with the other Medicaid provisions, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary scored a similar provision in the House bill that required increased redeterminations as saving $37 billion over the next decade.

While administrative and compliance costs must be weighed against possible savings, policymakers should look to ideas like this to ensure Medicaid benefits are only going to those who are eligible.

Further Means-Testing the Subsidy Schedule for the Individual Market

The BCRA makes a number of significant changes to the individual insurance subsidy schedule under the ACA, most significantly by pegging the schedule to lower value plans and repealing cost-sharing subsidies.

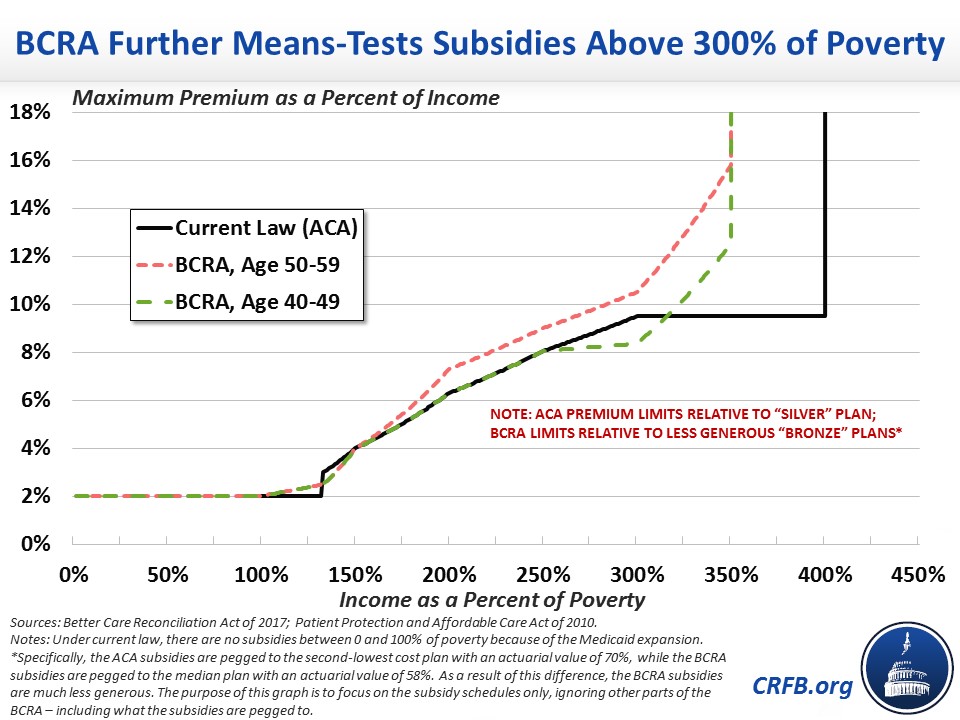

But the BCRA also includes changes to better target subsidies, both by age and by income. Under current law, the ACA offers a subsidy that effectively caps a silver plan premium at 2 percent of income for an individual at the poverty line and then gradually increases that cap to 9.5 percent of income at 300 percent of poverty. For individuals and families making between 300 and 400 percent of poverty, the subsidy continues to cap premiums at around 9.5 percent of income, after which the ACA offers no subsidy at all. In other words, subsidies for a family of four may continue to be available up to roughly $100,000 of income in 2017.

The BCRA scales back these subsidies at the higher end. For those ages 40-59, the BCRA offers a similar subsidy schedule to the ACA (though linked to less generous insurance). Between 300 and 350 percent of poverty, however, the caps are phased out rapidly, and above 350 percent of poverty – which would be about $86,000 per year for a family of four in 2017 – no subsidy is offered at all.

In 2013, CBO estimated cutting off subsidies at 300 percent of poverty would save over $100 billion but have little effect (and actually a slightly positive effect) on the number of uninsured – since employers would respond by offering more coverage of their own. By phasing out subsidies between 300 and 350 percent of poverty, the BCRA schedule (applied to current law) likely saves somewhat less but also avoids the larger subsidy cliff that would occur under the CBO option.

Importantly, the BCRA also varies the subsidy cap based on age. At 300 percent of poverty, premiums are capped at 4.3 percent for those under 30, 5.9 percent for those between 30 and 39, 8.35 percent for those between 40 and 49, 10.5 percent for those between 50 and 59, and 11.5 percent for those between 60 and 64. The fiscal impact of this change is unclear, but it has the potential to lower premiums and increase coverage by encouraging more young, healthy people to purchase insurance (while also reducing the premium cliff above 350 percent of poverty).

Policymakers should certainly consider options like this that reduce federal health spending – mainly by reducing subsidies for those a bit higher up the income scale – without reducing coverage.

Enacting a Per-Capita Cap on Medicaid Spending

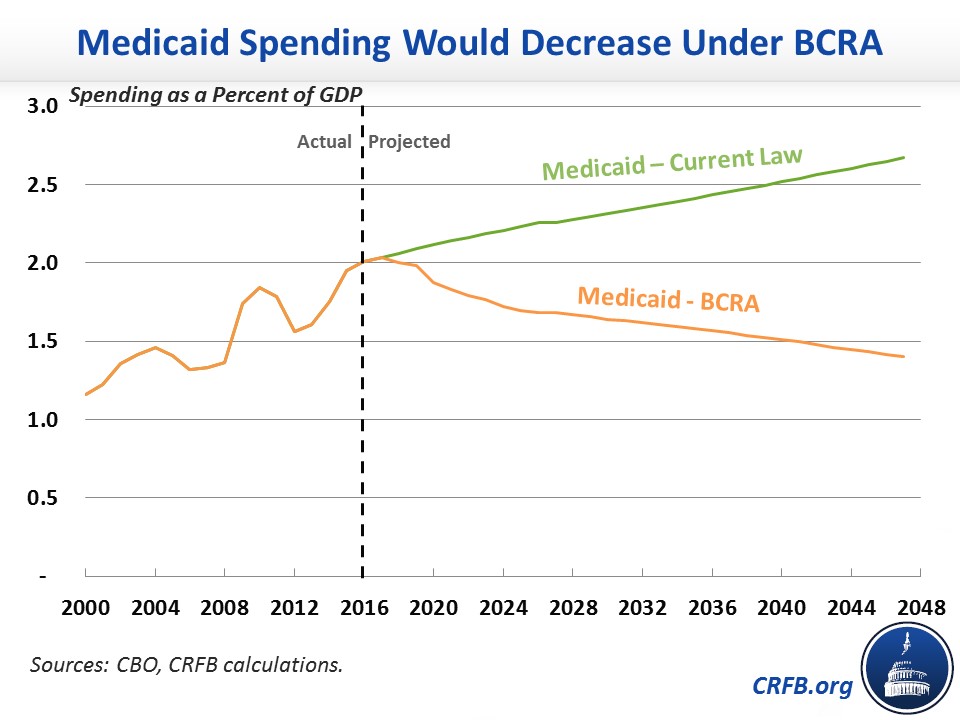

One of the biggest changes the BCRA makes is capping Medicaid spending on a per-capita basis. Medicaid is one of the largest and fastest growing programs in the federal budget, and under current law it will take up a larger and larger portion of the budget over time. Because Medicaid serves vulnerable populations, changes should be made carefully. But the open-ended nature of the current program provides little incentive to come up with solutions to this unsustainable growth.

The ACA effectively capped the growth of Medicare on a per-person basis, and a number of experts have suggested putting other rapidly-growing programs in a budget. A per-capita cap on federal Medicaid dollars going to each state would be one way to achieve this. In the 1990s, the Clinton Administration proposed a Medicaid per-capita cap, and in 2013 Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Representative Fred Upton (R-MI) proposed one as well.

The BCRA calls for a per-capita cap for each eligibility category of Medicaid spending beginning in 2020. That cap initially grows with or above medical inflation (CPI-M) through 2025 and then grows with a measure of economy-wide inflation (CPI-U) thereafter.

According to CBO, this cap would result in Medicaid costs growing slower than the economy. We estimate, based on CBO's projections, that Medicaid spending under the BCRA would fall from 1.7 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2026 under the BCRA to 1.6 percent in 2036 and 1.4 percent by 2046. By comparison, under current law costs would rise from 2.3 percent of GDP in 2026 to 2.4 percent in 2036 and 2.7 percent by 2046.

However, this cap might be too tight to be sustainable. In The Hill, CRFB senior vice president Marc Goldwein argued that any "cap must be set at a rate which can be reasonably met primarily with efficiencies and reforms." Since health costs grow much faster than inflation, states may find themselves unable to meet their caps even with aggressive efficiencies and reallocations of resources.

A well-designed and appropriately measured cap, though, could both encourage cost control from the states and limit the federal government's fiscal liability. A serious conversation about health care cost control should at least include discussion of such a cap.

***

While the future of the BCRA is unknown, policymakers should move forward on initiatives that would lower costs, improve care, and promote fiscal sustainability. The four features described above should all be on the table for consideration as policymakers grapple with how to stem the rapid growth of federal health care spending.