Is the 340B Program Living Up to Expectations?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program, enacted in 1992, gives hospitals and other providers serving disproportionately low-income populations the ability to buy outpatient prescription drugs at large discounts. It has come under increased scrutiny lately, though, as more and more people have questioned whether the program is actually fulfilling its purpose.

Criticism of the program has ramped up recently with charges that some hospitals are raking in large profits by taking the discounts from manufacturers and instead selling the drugs through hospital-affiliated clinics to higher-income/insured patients at the price the insurer pays. With eligibility for the 340B program determined based on a hospital's inpatient population, critics charge that this creates an incentive to serve more people in off-site outpatient settings located in wealthier areas. Hospitals deny this claim, saying that the program has served its intended purpose -- either the drugs are provided to vulnerable patients or the money is spent on expanding low-income access to care.

A new study published in Health Affairs by Rena Conti and Peter Bach examined characteristics of hospitals that participate in 340B and sided with the critics. They looked at those hospitals that also received Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments and saw how their communities changed over time. The number of 340B DSH hospitals has increased steadily since 340B's inception; however, the authors note a sizeable uptick in the growth rate of not only those hospitals but also of hospital-affiliated clinics starting in 2003. The number of clinics increased even more dramatically after 2010 when the Affordable Care Act expanded the types of providers that could qualify for 340B.

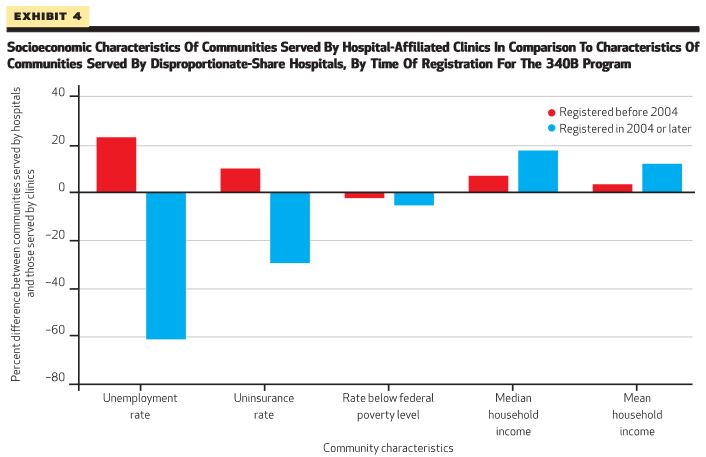

The authors look at the differences in the 2012 socioeconomic status of communities served by DSHs and affiliated clinics that registered before and after 2004 to see if the uptick in these facilities showed expansion into more affluent communities. Their data shows that post-2004 DSHs tend to serve fewer lower-income patients than the pre-2004 DSHs, although the median and mean household incomes were not significantly different. By contrast, patients at post-2004 clinics had significantly higher incomes and were better insured than those seen in pre-2004 clinics. The clinics, as the authors put it, "tended to serve communities with socioeconomic characteristics that were more similar to the average U.S. community," rather than poorer communities.

The authors conclude that their "findings are consistent with recent complaints by stakeholders and media reports suggesting that the 340B program is being converted from one that serves vulnerable communities to one that enriches participating hospitals and the clinics affiliated with them." They also posit that the 340B program may serve as another catalyst for the ongoing trend of hospitals buying outpatient clinics, by providing a pathway for hospitals serving a low-income, less-insured inpatient population to turn a profit on 340B drugs sold to wealthier patients in off-site outpatient clinics.

Safety Net Hospitals for Pharmaceutical Access (SNHPA) responded to the article with a number of counter-arguments. SNHPA said that the data only showed community data, not the characteristics of people the hospital served, so there could be a significant low-income population that is served within a more well-off community. They also said that there were many other factors driving hospital purchases of outpatient clinics, and the authors do not provide sufficient evidence to show that 340B is one of those factors. They also disputed the point that hospitals profited from 340B and that eligibility criteria did not serve as a meaningful limit on hospital participation.

The increasing criticisms of 340B are certainly worth monitoring to see if the program is meeting its purpose. Policymakers could examine whether eligibility criteria should be based on the demographics of the outpatient -- rather than inpatient -- population served (since the 340B program applies to outpatient drugs) or if transparency of hospital operations should be increased, so that health care safety-net resources are well-targeted.