Report: Deficit Falls to $483 Billion, but Debt Continues to Rise

This paper has been updated for FY 2015 and is now located here.

This paper has been updated for FY 2015 and is now located here.

Original October 8th: the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected the FY 2014 budget deficit at $486 billion. While the CBO works closely with Treasury to come up with their estimates, CBO's report was preliminary.

The FY2014 budget deficit totaled $483 billion, according to today’s statement from the Treasury Department. Although this is nearly 30 percent below the FY2013 deficit and 66 percent below its 2009 peak, the country remains on an unsustainable fiscal path.

In this paper, we show:

- Annual deficits have fallen substantially over the past five years, largely due to rapid increases in revenue (mostly from the economic recovery), the reversal of one-time spending during the financial crisis, small decreases in defense spending, and slow growth in other areas.

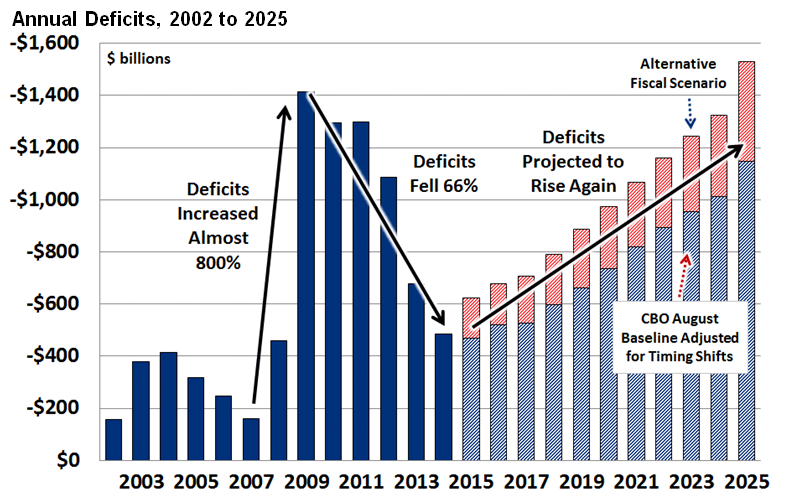

- Simply citing the 66 percent fall in deficits over the past five years without context is misleading, since it follows an almost 800 percent increase that brought deficits to record-high levels.

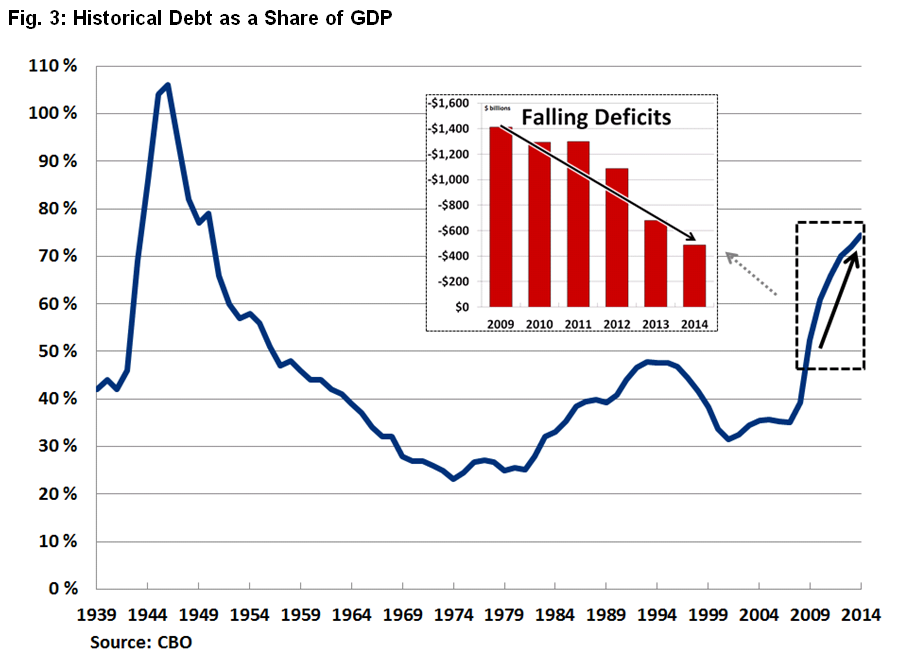

- Even as deficits have fallen, debt has continued to rise, more than doubling as a percent of GDP since 2007 to record levels not seen other than during a brief period around World War II.

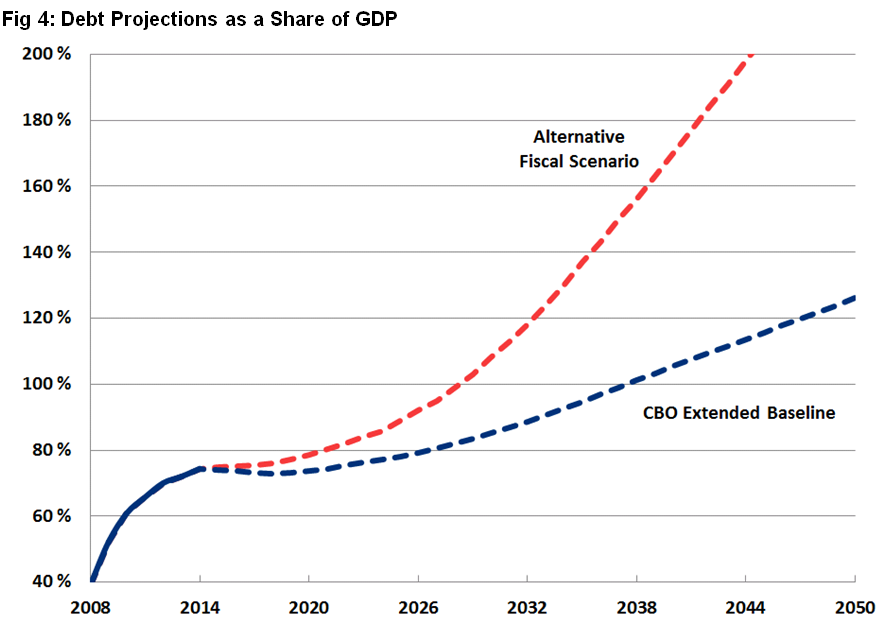

- Both deficits and debt are projected to rise over the next decade and beyond, with trillion-dollar deficits returning by 2025 and debt exceeding the size of the economy before 2040, and as soon as 2030.

Unfortunately, the recent fall in deficits is not a sign of fiscal sustainability.

The Deficit in FY2014

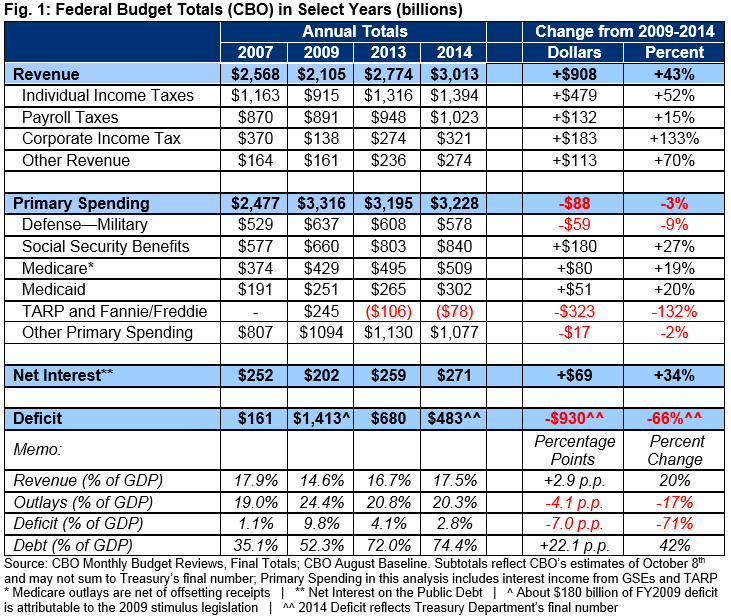

According to the Treasury Department, the federal deficit totaled $483 billion in FY2014 (an initial estimate from the Congressional Budget Office on October 8th estimated the deficit at $486 billion), with $3.02 trillion of revenue and $3.50 trillion of spending. The figure below largely reflects CBO’s estimates rather than Treasury’s final numbers.

Since 2009, the budget picture has changed significantly, with deficits falling by 66 percent, from $1.4 trillion to slightly under $500 billion. This reduction was driven largely by the 44 percent (roughly $900 billion) increase in tax collections, primarily a result of the economic recovery, which has helped restore revenues as a share of GDP from their depressed 2009 levels to about their historical average. New taxes from the American Taxpayer Relief Act and the Affordable Care Act have also played a role.

At the same time, nominal spending is nearly $15 billion lower than in 2009, even as the economy grows, and inflation erodes its value. The decreases are largely driven by the absence and reversal of financial rescue and economic recovery spending through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the stimulus, though defense spending has also fallen. Most other categories of spending have grown in nominal terms; however, Medicare, non-defense discretionary spending, and interest costs have grown more slowly than was expected.

Importantly, at $483 billion (2.8 percent of GDP), last year’s deficit was still substantially higher than the pre-recession deficit of $161 billion (1.1 percent of GDP) in 2007.

Deficits Fell From Record Levels But Will Rise Again

A 66 percent drop in annual deficits since 2009 is certainly significant, but when put in context it is less impressive than some would suggest. The rapid fall was from record-high levels and followed a rapid increase. At $1.4 trillion, the 2009 deficit was the highest ever as a share of the economy except during World War II (and in real dollar terms, the highest in history), having increased 779 percent from 2007 as a result of the Great Recession and measures enacted to combat it.

Moreover, while legislated spending reductions, tax increases, and other factors played a role, the end of trillion-dollar deficits was mostly the expected result of the economic recovery and the fading of measures intended to boost the recovery. As unemployment rates have fallen and GDP recovers, revenue collection has risen to more normal levels and countercyclical spending in areas such as unemployment insurance and food stamps has begun to subside. Meanwhile, stimulus and financial rescue measures enacted to speed the recovery have mostly wound down.

Unfortunately, even with these gains, the deficit remains more than three times as high as in 2007 (1.7 percentage points higher as a percent of GDP) and is projected to grow over time. Under CBO’s current law baseline, annual deficits will return to trillion-dollar levels by 2025. Under their more pessimistic Alternative Fiscal Scenario, the deficit will reach $1.5 trillion in 2025, exceeding the nominal-dollar record set in 2009.

As Deficits Fall, the Debt Keeps Rising

Arguably the most important metric of a country’s fiscal health is its debt-to-GDP ratio. And unfortunately, even as deficits have fallen the last five years, debt has grown. Indeed, over the same period that deficits fell by 66 percent, nominal debt held by the public grew by 69 percent – from $7.5 trillion to $12.8 trillion. As a percent of GDP, debt has grown extremely rapidly, from 35 percent of GDP in 2007 to 52 percent of in 2009 and to over 74 percent in 2014.

Falling deficits have not prevented the debt from growing; rather, they have only slowed down the growth trend. While the debt-to-GDP ratio may stabilize for a few years, debt is projected to continue growing faster than the economy over the long run. As the population ages, health care costs grow, and interest rates rise to more normal levels, CBO projects debt will rise from 73 percent of GDP in 2018 to 77 percent of GDP by 2024, and will exceed the size of the economy before 2040. Under CBO’s Alternative Fiscal Scenario (AFS), debt will exceed the size of the economy before 2030.

Conclusion

The fact that deficits have fallen from their trillion-plus dollar levels is an encouraging sign that the economy continues to recover. Unfortunately, Washington’s myopic focus on short-term deficits has likely slowed the recovery by cutting deficits somewhat too fast in the short term while leaving substantial imbalances in place over the long term.

While the deficit has indeed dropped significantly, this drop followed a massive increase, was largely expected, and does not suggest the country is on a sustainable fiscal path. Currently, debt levels are at historic highs and projected to grow unsustainably over the long run.

In only a decade, deficits are projected to again exceed $1 trillion, and within 15 to 25 years debt is projected to exceed the entire size of the economy.

Policymakers must work together on serious tax and entitlement reforms to put debt on a clear downward path relative to the economy, not declare false victories and sweep the debt issue under the rug.

Download a printer-friendly version of the paper here.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-