What the Wall Street Journal Gets Wrong on the SGR

This weekend, The Wall Street Journal announced its support for the permanent Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) replacement currently being negotiated in Congress. Although full details are not yet available, the legislation apparently has about $200 billion of costs, accompanied with roughly $60 billion of offsets – half from beneficiaries and half from providers. In other words, the legislation is largely unpaid for and would add about $140 billion to deficits through 2025, before interest.

Despite its long-standing support for controlling the growth of Medicare costs, The Wall Street Journal endorses this Medicare spending increase under the premise that the SGR itself is a “fiscal deception,” and that past offsets used to pay for avoiding it “are usually fake.” However, for the most part, these arguments do not stand up to scrutiny.

Below, we explain why many of their claims are either inconsistent with the facts or else counterproductive to achieving the overall goal of reforming Medicare and reducing its future costs.

Claim #1: Ending the SGR does not add to the deficit.

The Wall Street Journal claims that politicians are under a false “impression that the formula leads to real savings, and thus ending it adds to the deficit” and that “the SGR merely lets Congress hide the future spending it is going to do anyway.” Yet while it is true policymakers have continuously prevented the across-the-board SGR cuts from happening, they have also offset the cost of doing so 98 percent of the time. As Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times explained, “With only a few exceptions, Congress simply cuts other parts of the budget to compensate for the extra money for the doctors. And that money almost always comes from Medicare or other health care programs."

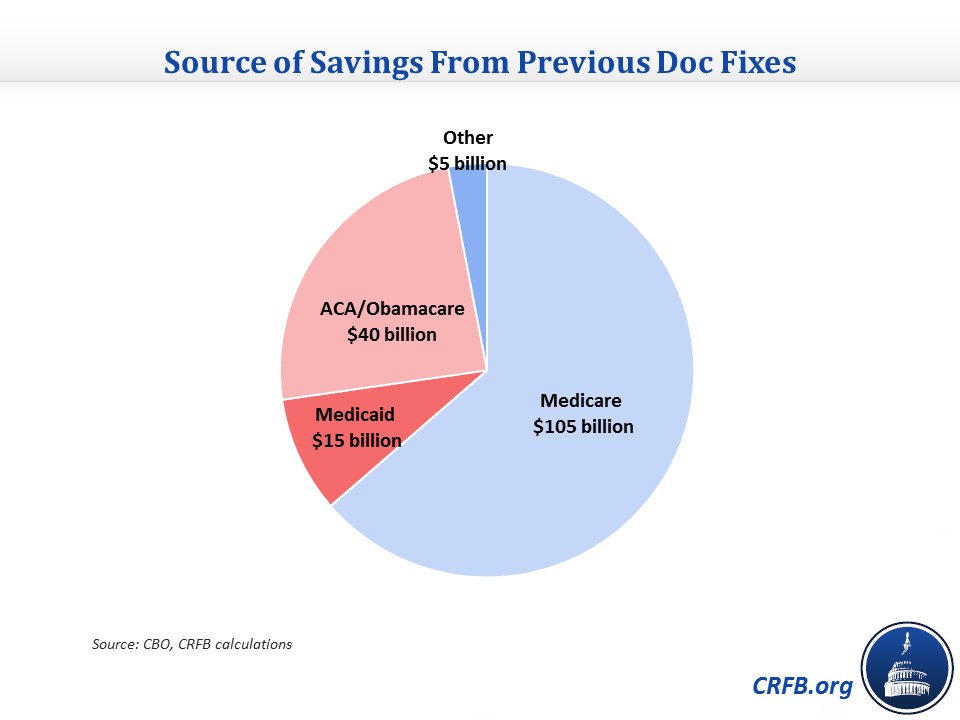

In fact, our analysis shows that these offsets -- nearly all of which are health-related -- will save about $165 billion (before interest) through 2025.

Claim #2: Doc fixes should be considered from a current policy baseline.

The Journal describes the view that the doc fix counts as a spending increase as the "reality-distortion field of baseline budgeting." Essentially, the editorial takes a current policy perspective, arguing that because policymakers never let the cuts happen, they don't count as real savings; thus, undoing the SGR is not an actual cost. Leaving aside the point about offsets we have already made, this is not the way the law views it nor should it be the way anyone else views it. Statutory pay-as-you-go rules require that mandatory spending or tax cuts be offset over ten years, and there is no exception for the SGR. Further, allowing lawmakers not to pay for a doc fix despite the fact that they specifically made previous doc fixes temporary to avoid facing up to the much larger cost of making it permanent would allow the cost to disappear from the budget process.

The WSJ itself also disputed this view barely five years ago, criticizing an unpaid-for House Democratic doc fix in a November 2009 editorial "The $1.9 Trillion Gimmick: The Democrats' 'doc fix' for Medicare payments would shock Madoff." The Journal described the bill as follows:

Everyone agrees that the SGR must be corrected, given that steeper cuts in Medicare's submarket price controls mean that many physicians will refuse to treat seniors—but not without cleaning up the mess created by the prior cost-control inspirations of the political class. A new Heritage Foundation study by the former Medicare trustee Thomas Saving and economist Andrew Rettenmaier finds that eliminating the SGR without offsets will increase Medicare's unfunded liabilities by $1.9 trillion over the next 75 years. Given that the entitlement is already about $39 trillion in the hole (give or take a few trillion), the SGR fix alone is a European-style value-added tax waiting to happen, not including the huge new permanent spending commitments created by ObamaCare.

But where the Journal called ignoring the doc fix's cost gimmicky accounting in 2009, they now view acknowledging the cost as gimmicky.

Claim #3: SGR “pay-fors are usually fake."

In contrast to last year when the Wall Street Journal simply described the SGR as “budget dishonesty," this editorial does acknowledge that Congress has generally paid for “doc fixes” to avoid the SGR cuts. But according to the WSJ, “the 'pay-fors' are usually fake—mostly the failed habit of fiddling with this or that price-control dial in Medicare.”

While the Wall Street Journal may not agree with many of the cuts, there is little basis to call them “fake.”

First, many of the policies the Wall Street Journal describes as “price-controls” are actually just changes in the amount Medicare will reimburse for particular services based on their value and costs. Often based on recommendations from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), many of these changes cut excessive payments or otherwise reduce the amount of waste, fraud, and abuse in the system. In the past, both parties have supported such provider reductions – indeed, President Bush’s final budget included almost $450 billion of such cuts over ten years.

In addition, many of the offsets for doc fixes were not simple reductions in provider payments, but instead small structural reforms aimed at improving incentives and encouraging competition within Medicare. Last year’s doc fix alone included policies to allow for value-based purchasing for skilled nursing facilities, pay competitive market-based prices for clinical labs, promote technology-driven evidence based care, and update Medicare’s “bundled payment” program for end stage renal disease (which itself was created in another doc fix to promote better health care at a lower price).

Finally, it is worth noting that nearly one quarter ($40 billion) of the $165 billion that has been saved as a result of doc fixes took the form of reductions to the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) – mainly by increasing allowed recaptures of overpaid insurance subsidies. Surely the Wall Street Journal, which has warned many times of the costs associated with the ACA, would not consider these savings to be “fake."

Claim #4: CBO savings estimates do “not quantify how providers change their behavior in response to different incentives.”

To bolster the argument that the $165 billion of doc fix offsets are not real, the Journal argues that this “number is merely the sum of the Congressional Budget Office’s static estimates of SGR bills before they pass [and] does not quantify how providers change their behavior in response to different incentives.” This demonstrates a misunderstanding of how CBO estimates work.

While it is true that our estimates were generated largely by summing CBO’s projections (read our methodology here), CBO’s projections do indeed incorporate a wide range behavioral effects – including exactly the behavior the Journal is worried CBO is not incorporating. As CBO explains (emphasis added):

CBO’s analysts assess the extent to which proposed policies would affect people’s behavior in ways that would generate budgetary savings or costs, and those effects are routinely incorporated in the agency’s cost estimates. For example, the agency’s estimates include changes in the production of various crops that would result from adopting new farm policies, changes in the likelihood that people would take up certain government benefits if policies pertaining to those benefits were altered, and changes in the quantity of health care services that would be provided if Medicare’s payment rates to certain providers were adjusted.

Indeed, the only type of behavior response the CBO does not typically incorporate is macrodynamic changes in large variables like GDP, inflation, and interest rates that are unlikely to be affected by the modest reductions in health spending enacted with each doc fix.

Claim #5: The inclusion of small but important “entitlement changes like means-testing [that] yield dividends in perpetuity” make this SGR bill worth passing.

The WSJ rightly points out that the SGR bill currently being negotiated does have some positive fiscal aspects, one being an increase in means-tested premiums. “Entitlement changes like means-testing,” they argue, “yield dividends in perpetuity, lowering Medicare’s $28 trillion unfunded liability [and] the improvements Republicans might secure here are incremental but important over the long run.”

We agree such changes are important. But if the goal is to maximize the size of important beneficiary reforms, the Journal seems to be going about achieving this goal all wrong. After all, just a year ago it endorsed an SGR bill with no changes to spending on beneficiaries. Moreover, with a rumored savings of $30 billion-$35 billion, the savings from beneficiaries in this SGR deal would be only about one-third the size of the beneficiary savings ($93 billion) in the President’s own budget – proposals made unilaterally before negotiations with Republicans.

Surely if an agreement to offset less than a third of the SGR reform leads to agreement of $30 billion or beneficiary savings, an agreement to offset the entire $200 billion package could yield much more. And such an agreement is certainly possible, either through reconciliation or other fiscally responsible negotiations.

Even without a long-term agreement, it isn’t clear that this reform package would be worth the cost for conservatives. After all, the $30 billion from Medicare beneficiaries in the plan is smaller than the $40 billion of Affordable Care Act savings generated by simply continuing the regular ritual of temporary doc fixes.

Claim #6: This is the best deal Medicare reformers can get.

Implicit in the WSJ’s argument is the suggestion that policymakers will be unable to agree to substantive offsets for SGR reform and should therefore pass the legislation as is rather than worry about “the bottleneck [of] 'paying for' SGR repeal.” After all, given the concern about Medicare’s $28 trillion unfunded liability, the Journal would surely support coupling the SGR fix with more Medicare reforms if it believed it were possible.

Fortunately, identifying $200 billion of health reforms is quite possible. Indeed, this number is small relative to recent health reform proposals. The President’s budget alone includes $440 billion of gross savings. The most recent Simpson-Bowles plan included $600 billion. And the most recent Domenici-Rivlin plan included more than $1 trillion. In addition, opening health care savings offers during the Super Committee ranged from $475 billion to $685 billion, and final offers in the fiscal cliff negotiation ranged from $400 billion to $600 billion.

Considering the size of these packages, identifying $200 billion worth of savings shouldn’t be that difficult, particularly if coupled with the “sweetener” of a permanent SGR reform. Our PREP plan includes $215 billion of savings, including $100 billion from reforming provider incentives to more efficiently deliver medicine, $100 billion from reforming beneficiary incentives in ways that reduce beneficiary and taxpayer costs, and $15 billion from cutting overpayments within Medicaid.

Of course, the PREP Plan is only one of many strategies to offset SGR reform. And we welcome others, so long as they pass the basic test of fiscal responsibility.