Republican Study Committee Releases FY 2019 Budget

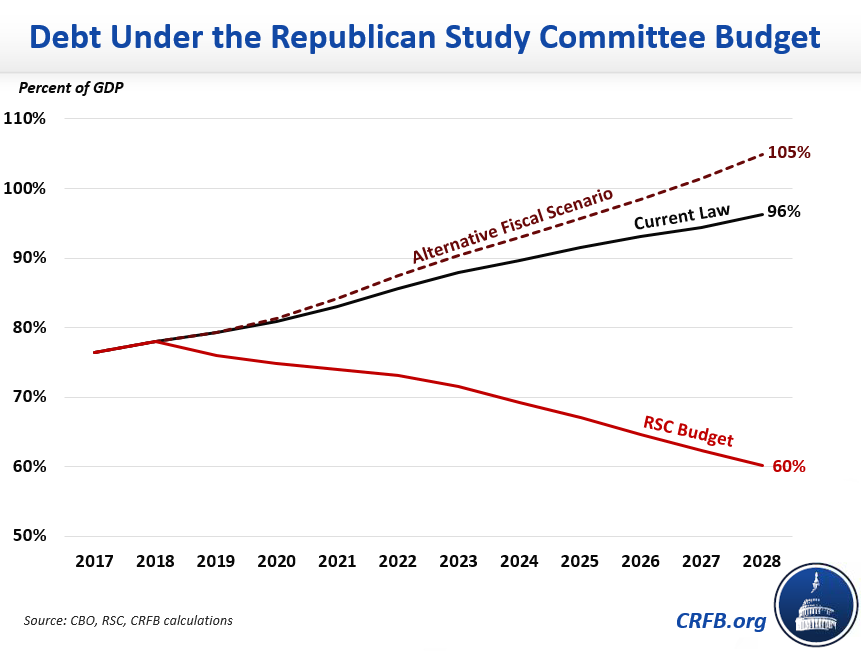

While the House and Senate Budget Committees have yet to release a budget for FY 2019, the Republican Study Committee (RSC) has released its own budget calling for $10.7 trillion in deficit reduction over ten years and a balanced budget by 2026. As a result, debt would decline from 78 percent of GDP at the end of 2018 to 60 percent in 2028 instead of rising to 96 percent as CBO projects under current law.

According to the RSC, the budget would reduce spending by $12.4 trillion over ten years, with spending falling from 20.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 17.1 percent in 2028. These cuts would be implemented rapidly, with spending in 2019 falling to 17.6 percent of GDP, about 17 percent below baseline levels. The RSC budget would also reduce tax revenues by about $1.7 trillion. Revenues would fall from 16.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 16.3 percent in 2019 before rebounding to about 17.1 percent by the end of the budget window.

Policy Changes in the RSC Budget

| Policy | 2019-2028 Savings |

|---|---|

| Extend Expiring Tax Cuts | -$771 billion |

| Net Discretionary Spending Cuts | $2,777 billion |

| Overhaul Medicare | $1,354 billion |

| Repeal Obamacare (Including Taxes) and Enact Medicaid/CHIP Reforms | $2,872 billion |

| Reform Social Security | $259 billion |

| Reduce Other Mandatory Programs | $2,962 billion |

| Interest Savings | $1,273 billion |

| Total Savings | $10.7 trillion |

Source: Republican Study Committee, CRFB calculations.

Taxes

The RSC budget would permanently extend the expiring individual tax cuts and expensing provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), lowering revenues by about $771 billion through 2028. It would also repeal the tax provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), reducing revenues by another $910 billion. The budget also includes several smaller tax proposals such as eliminating marriage penalties in the tax code and introducing universal tax-free savings accounts, presumably on a revenue-neutral basis.

Discretionary Spending

The budget would lower nondefense discretionary funding in FY 2019 to under $355 billion, or about $242 billion less than the $597 billion cap established in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. The budget would also zero out the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account and cap exempt nondefense spending, placing the defense funds in the base defense category and eliminating the nondefense OCO funds. It would set FY 2019 defense budget authority at $716 billion, the total amount requested by President Trump (including OCO) and slightly lower than CBO's baseline amount, but increase defense spending on net over the budget window. Over ten years, discretionary outlays under the budget would be nearly $2.8 trillion lower than CBO’s baseline levels.

Health Care

The budget repeals the ACA and replaces it with the RSC’s American Health Care Reform Act, which provides a standard deduction for health insurance, allows the purchase of health insurance across state lines, and reforms the medical liability system among other changes. The budget also proposes block granting Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at pre-ACA levels along with a state option of per-capita cap funding. It would also limit Medicaid eligibility to U.S. citizens and establish work requirements for able-bodied adults on the program.

The budget would adopt a premium support system for Medicare starting in 2023 while preserving traditional fee-for-service Medicare as an option. It would also increase Medicare’s eligibility age to align with Social Security's age, combine Parts A and B, and increase premiums and means testing.

Social Security

The RSC budget make Social Security sustainably solvent by implementing a slightly modified version of Representative Sam Johnson’s (R-TX) “Social Security Reform Act,” which would slow initial benefit growth for higher earners, gradually raise the normal retirement age to 70, and eliminate annual cost-of-living adjustments for higher earners while using the more accurate chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) (currently used for the tax code) for other beneficiaries.

Among the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) proposals, the budget recommends several of the reforms put forward by the McCrery-Pomeroy SSDI Solutions Initiative. The budget would also require beneficiaries to have worked more in recent years, create a new demonstration project for experience-rating the SSDI payroll tax, update eligibility requirements, prevent double-dipping between SSDI and unemployment insurance, end SSDI eligibility for those who have reached Social Security's early retirement age, and reform the appeal process.

Other Mandatory Programs

The budget includes a host of changes to reduce spending on other mandatory programs. The RSC proposes several reforms to income security programs, largely focusing on adding or strengthening work requirements, tightening eligibility, and shifting certain spending or responsibilities to the states. For example, changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program include converting the program into a block grant and requiring states to finance 25 percent of the total costs, eliminating the ability for states to waive work requirements, and ending categorical eligibility, among other changes.

Other mandatory spending cuts include scaling back and eliminating various farm subsidies, repealing the in-school interest subsidy, reducing federal employee benefits, and adopting the chained CPI government-wide.

Budget Process Reforms

Finally, the budget recommends many reforms to the budget process. The reconciliation process would be expanded to allow for changes in discretionary programs and for multiple reconciliation bills each year. The budget baseline would be altered to assume discretionary spending is constant at its current level and that trust funds are not allowed to spend in excess of their resources.

Other proposed changes include requiring the use of fair-value accounting to estimate the cost of credit programs; including interest costs in scores of legislation; aligning the fiscal year with the calendar year; changing the budget treatment of highway programs; moving all programs "on-budget;" and prohibiting Congress from adjourning after the end of the fiscal year unless it has completed action on the budget resolution, regular appropriations acts, and applicable reconciliation bills.

***

While many of its spending cuts are more aggressive than the political climate is likely to allow, the RSC deserves great credit for putting out a budget in a year where no official budget has yet been put forward by the House or Senate Budget Committees. Not only does its budget put debt on a downward path through major reductions in federal spending, it also sets a particularly good precedent by including reconciliation instructions for all of its mandatory savings and avoiding gimmicks such as rosy economic assumptions.