Repeal and Delay Shouldn't Increase Near-Term Deficits

Last week, we estimated that repealing the Affordable Care Act's ("Obamacare" or "ACA") revenue and coverage provisions would save about $750 billion over a decade ($950 billion under dynamic scoring).

In 2015, the ACA repeal reconciliation bill relied on a "repeal and delay" strategy, where revenue increases and mandates were repealed immediately but other coverage provisions were maintained for several years. This approach would save significantly less by our estimates – $300 billion if coverage is continued for four years and $550 billion if coverage is continued for two years. The ACA also included savings in the health care system to pay for expanded coverage, but the reconciliation bill largely kept these.

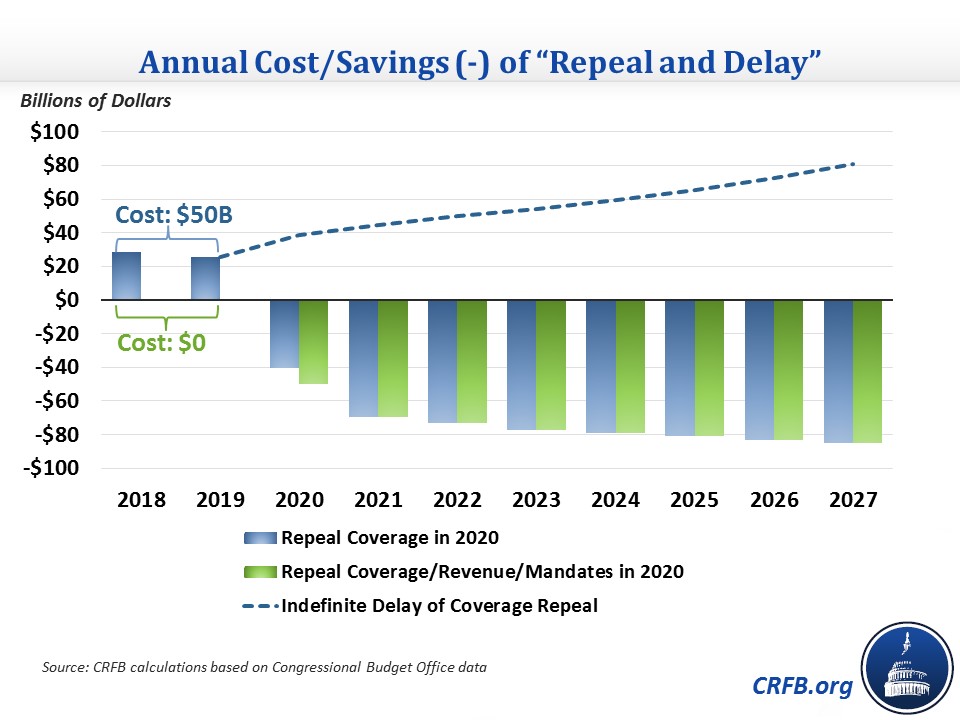

"Repeal and delay" also increases the deficit in the near term because repealing the tax provisions would cost more than eliminating the mandates would save. If policymakers followed through on this plan – repealing mandates and tax increases immediately but the Medicaid expansion and exchange subsidies after two years – they would add about $50 billion to the deficits over the next two years before savings begin.

If they repealed coverage provisions with a four-year delay, the plan would add about $135 billion in deficits over those four years.

The near-term deficit impact would be negligible if all revenue and mandate provisions were retained as long as coverage provisions were.

At times, it can make sense to increase near-term deficits and pay for this cost over time. For example, policymakers might enact stimulus during a recession to help facilitate an economic recovery while temporarily adding to the debt (preferably coupling the stimulus with longer-term debt reduction measures). Or they might frontload new investments relative to pay-fors in order to take advantage of low interest rates. And as a practical matter, there are times when new spending is needed quickly while offsets simply take time to phase in.

Repeal and delay is not one of these cases where near-term deficit increases are justified. Its costs are not new stimulus or investment but repeal of an existing program. Its offsets have no need to phase in since they are already in place.

Moreover, adding to the deficit in the near term could set the stage to further increase the deficit. Once the ACA's tax offsets have disappeared, lawmakers may find they have both less desire to repeal its coverage provisions and fewer funds to responsibly finance a replacement. Instead, they could resort to temporary – and perhaps deficit-financed – extensions of existing subsidies and Medicaid funding. Continuing such extensions indefinitely would ultimately cost $500 billion over the next decade.

Rather than putting the cart before the horse in repealing the ACA's tax provisions before the coverage provisions, their repeals should be linked. If the repeals occurred together, it is much more likely that they would be delayed together, rather than a situation where the tax provisions would be reinstated after having been repealed for a few years.

If repeal and delay is pursued, both the coverage provisions and offsets should be delayed by the same time period. The coverage provisions should not have a longer delay.