Official Dynamic Score Shows Senate Tax Bill Will Still Cost Over $1 Trillion

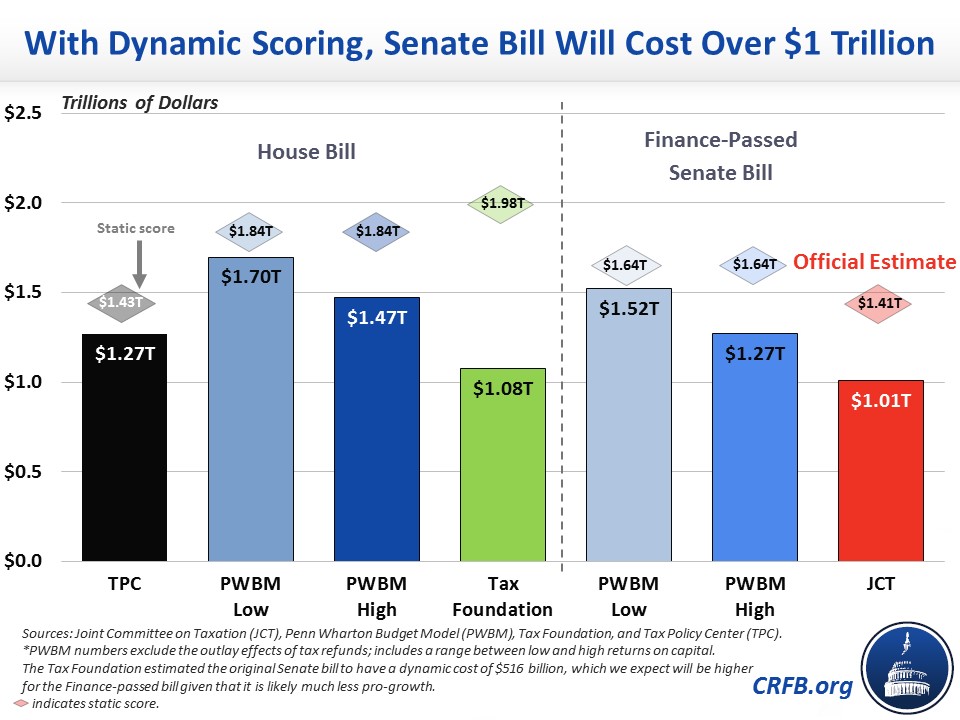

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) has released its official dynamic score of the Senate tax plan as passed by the Senate Finance Committee, finding the bill would increase Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 0.8 percent over the next decade. This would amount to less than a 0.08 percentage point improvement in the average annual growth rate over the next decade. As a result, JCT estimates the bill would generate $407 billion of budgetary feedback, reducing net costs from $1.4 trillion to just over $1 trillion over a decade (these estimates do not account for over $500 billion of gimmicks). In other words, growth would pay for only three-tenths of the conventional cost of the bill and a smaller share of the true cost after gimmicks.

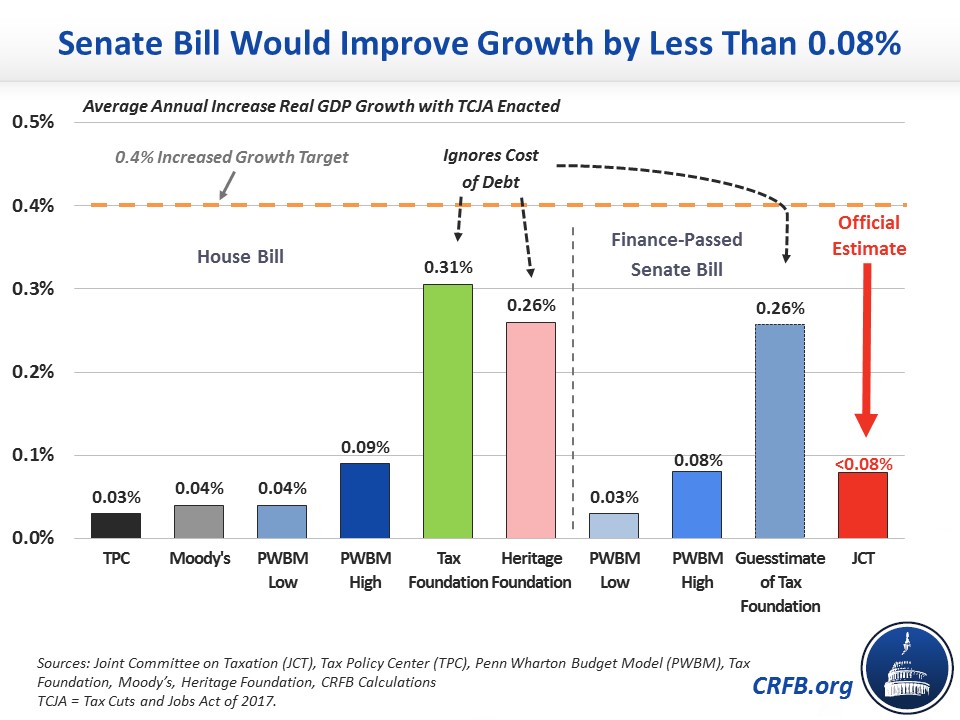

Today's JCT estimate confirms that while tax reform will improve economic growth, the current debt-financed tax bill will do so only modestly – much less than the 0.4 percentage points per year some have claimed and not nearly enough for the tax cuts to pay for themselves.

Under current rules, JCT is required to produce dynamic scores of significant legislation when possible. Their models incorporate the effect of lower tax rates, a broader tax base, international tax reforms, and higher debt on the capital stock, labor force participation, employment, consumption, and the total size of the economy.

JCT finds that the Senate bill would boost the size of the economy by 0.8 percent on average over the next ten years. Though they don't lay out a specific path, JCT says that the net effect on GDP would be smaller in the later years after various provisions have expired. This suggests the average growth rate over the next decade would improve by well less than 0.08 percentage points per year – improving average growth from 1.84 percent to roughly 1.9 percent. The effects would be smaller in the second and third decades due to the individual tax provisions expiring and the cumulative effect of short-term debt on longer-term growth.

These estimates are broadly similar to other outside estimates that incorporate the effects of debt and have projected that this or the House bill will improve the growth rate by between 0.03 and 0.09 percentage points per year.

At the same time, these growth projections are modestly lower than projections of prior tax reform plans. This is in part because most prior plans were more comprehensive (many included permanent full expensing, for example), did not sunset major parts of the plan, and were deficit neutral. While lower rates can promote growth, higher debt can stunt it.

JCT's estimates are significantly lower than those of the Tax Foundation and Heritage Foundation (though importantly, neither projects 0.4 percentage points more of growth) in large part because neither of these estimates appear to account for the economic cost of debt.1 Indeed, even JCT's estimates do not fully account for the negative impact of debt: JCT averages three different models, two of which assume debt increases are corrected through future legislation. Without that assumption, JCT might estimate an even smaller improvement to growth.

As a result of a larger economy under the bill, JCT projects tax reform will generate $458 billion of feedback revenue. They also project the added growth will cause interest rates to rise, leading to $51 billion more in spending. The net effect is the dynamic effects of tax reform will reduce the bill's costs by $407 billion. In other words, the tax cuts will pay for three-tenths of their $1.4 trillion conventional cost.

This represents a far cry from claims that tax reform will be fully paid for with economic growth; in fact, no estimate so far has reached such a conclusion. All estimates we're aware of regarding the current Senate bill show it will cost $1 trillion or more even after incorporating economic growth effects.

Ultimately, JCT's estimates are just that – estimates. But they are sophisticated, impartial, and designed to show the center of a range of likely outcomes. Given these modest estimates and the reality that no other estimator has found the Senate bill would pay for itself, policymakers would be wise to adjust the Senate bill to ensure it meets basic standards of fiscal responsibility.

1 The bill adds $1.4 trillion to deficits before looking at economic effects. When the government issues new debt to cover those deficits, it must be purchased from increased foreign investment, higher domestic savings, or a shift in domestic savings away from private investments. This shift is known as "crowd out,” and over time it leads to lower private investment and therefore slower economic growth.

Most sophisticated modelers assume a mixture of higher savings, increased foreign investment, and crowd out absorbs higher debt – consistent with substantial evidence that all three are occurring. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for example, assumes that a $1 increase in deficits leads to $0.33 in private investment being crowded out. In other words, roughly one-third of new debt is purchased in place of productive private investments. Thus, higher debt has some negative impact on economic growth.

The Macroeconomic Economic Growth (MEG) model, which is one of the models JCT uses that accounts for 40 percent of the growth estimate, also assumes an aggressive response by the Federal Reserve, which is consistent with the near-full employment in today's economy. Some of the economic growth provided by tax cuts will be stimulus – a short-term boost caused by putting more money in people's pockets. However, this short-term boost does not affect the long-run factors that lead to economic growth: the supply of labor, capital, or productivity. In today's environment, it would be typical for the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates, which reduces the ease of borrowing and counteracts this short-term stimulus. This behavior would be consistent with the Fed's mission to maintain inflation at 2 percent, as Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen indicated earlier this week.