Not Living Up to Potential: CBO Sheds Light On Its Economic Projections

As we've mentioned frequently, budget projections and economic forecasts are inextricably linked in determining both the nominal dollar budget numbers and their size compared to GDP. Naturally, the ten-year projections that budget agencies like the Congressional Budget Office and Office of Management and Budget make are very uncertain, so deviations from those forecasts can have profound effects on the budget. A recent CBO report helpfully provides some background on how they make their economic projections and in particular, why they assume that the economy will never actually reach potential GDP.

For background, potential GDP is the amount of output the economy would produce if it was at full capacity but not at a level which would risk accelerating inflation. Thus, it does not represent literally the maximum possible output at the time but rather a trend line around which actual GDP moves during the business cycle. Thus, the growth rate of potential GDP and its relationship to actual GDP are very important in longer-term budget projections.

Of course, actual GDP is currently below potential by more than 2 percent, and it has been below it since mid-2006 and for 12 of the past 13 years. Here's how CBO describes its incorporation of cyclical effects:

For roughly the first half of its 10 year projection period (which currently runs through 2025), CBO projects the growth of actual output by estimating both the potential and the cyclical components of economic activity. For the latter part of the projection period, however, CBO does not estimate cyclical components.

In other words, CBO attempts to project economic growth in the first five years of its budget window but relies on a simplifying assumption that the economy is in “steady-state” in the second five years, rather than trying to predict booms or busts. In the past, CBO assumed that actual GDP would be exactly equal to potential GDP in this steady state. However, recently CBO adjusted that assumption.

Starting in last year's February baseline, CBO assumed that the economy would only reach 0.5 percent below potential and grow at the same rate as potential GDP thereafter. As before, CBO does not attempt to project the business cycle in the second five years, instead assuming an average of likely outcomes.

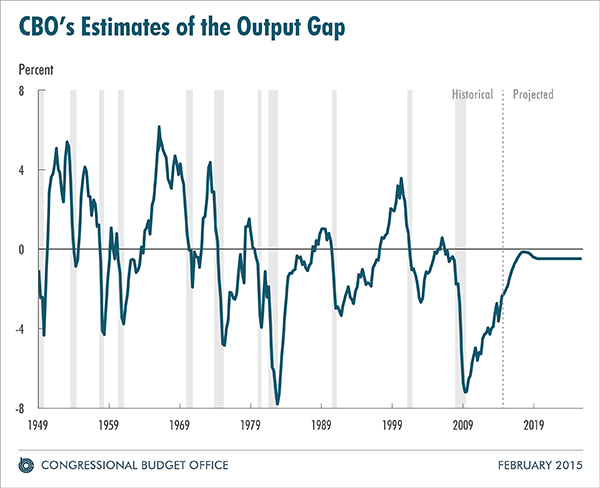

CBO explains that it chose the assumption that actual GDP would remain below potential because it represents the average output gap between 1961 and 2009 (including 2009-2014 about doubles it) and because actual output has been below potential on average in every business cycle since the one starting in the mid-1970s.

That last point is important because the 1961-2009 average is skewed by the early years of that period; in fact, the average output gap was larger than 0.5 percent in four of the past five business cycles (the 1990s being the exception), whereas the 1961-1974 period saw output exceed potential by 1.5 percent. In general, the economy tended to stay above potential between 1949 and 1974 for lengthy periods, often by several percent. Since then, though, output gaps have often persisted for several years, and periods of positive output gaps have been relatively small and short-lived.

CBO has a number of possible explanations for the less favorable business cycles of the past 40 years. They cite possibilities such as the economy's lack of a strong bounceback from bad shocks, the increasing importance of a services in the economy (which lag behind the business cycle more than manufacturing), and the ineffectiveness of monetary policy in stimulating the economy. It also suggests it is possible that CBO projections of potential GDP are wrong, though CBO presents considerable evidence to suggest this is unlikely and further explains that if this were the explanation, it would still suggest the same methodology for estimating GDP.

While the assumption that GDP won't reach potential in the steady state would seem to have significant fiscal implications, CBO indicates that it has little effect on nominal deficit numbers overall, because the lower revenue and higher spending generated by the output gap is offset by lower interest rates from the Federal Reserve trying to get the economy back to full potential. However, since GDP would be lower, debt as a percent of GDP (and other budget metrics as a share of GDP) would be higher; assuming no change in nominal debt, having GDP 0.5% lower than potential increases the ratio by 0.4 percentage points.

This report, while somewhat technical, sheds important light on how CBO makes its current economic forecast. In short, it increasingly reflects the reality that business cycles have more downside than upside.