How CBO Accounts for Anti-Fraud Efforts

Fraud -- along with the closely related waste and abuse -- is too often cited as a big factor affecting our high deficits, even though this is not the case. Nonetheless, rooting it out can be a non-controversial path to marginally reduce spending and to help assure Americans that their taxes are not being wasted. A new CBO report discusses anti-fraud efforts in federal health care programs and how they are accounted for in the agency's scoring of costs and savings in legislation.

There are a number of agencies and mechanisms tasked with reducing fraud in health care programs. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), of course, is the main one. But there is also the Health and Human Services Inspector General, the Department of Justice, and the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control (HCFAC) program, a dedicated fund for pursuing fraud that has both a mandatory and a discretionary appropriation.

Despite this anti-fraud efforts, significant improper payments (a broader category than fraud) of $65 billion in health care still exist, at least some of which is fraud. CBO discusses a number of different strategies to reduce it, including increasing anti-fraud funding, allowing new authority for agencies to pursue fraud, shifting funds to activities expected to provide higher returns, and increasing penalties.

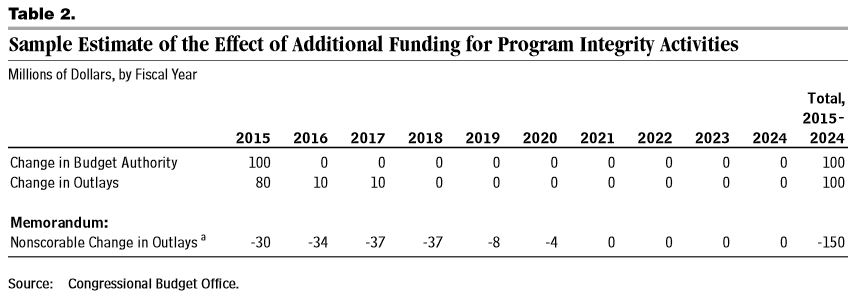

In terms of the first strategy, based on previous efforts, CBO assumes that an additional dollar of HCFAC spending yields $1.50 of savings (see the table below for an example). The Budget Control Act allowed for adjustments to the discretionary spending caps for HCFAC totaling $3 billion in additional funding, providing estimated savings of $3.7 billion. (The ratio is less than 1.5 to 1 in this case since it takes time for the savings to materialize). Notably, however, these net savings cannot be used for budget enforcement like pay-as-you-go rules because of their uncertain nature.

The other actions lawmakers take have much more specific effects for CBO to evaluate. CBO would have to determine whether new authorities granted would be used at all and, if so, what effect they would have. Shifting resources could produce savings or costs depending on their relative returns and their feasibility compared to current law. Increasing financial penalties for committing fraud generally raises revenue from penalties collected, but the increases have generally been too small to actually deter fraud by themselves. CBO also found that the power to penalize providers by excluding them from participating in federal programs has rarely been used, so extending such authority may not be judged to have significant effects.

Reducing health care fraud is important to ensure that all spending goes to legitimate expenses for each program. The CBO report should enlighten the budgetarily-inclined on how those proposals would be scored if lawmakers intend to get savings from them.