Growth Just Hit 4.1 Percent – Don't Expect It To Last

The Bureau of Economic Analysis today released its initial estimate that the economy grew at a 4.1 percent annualized rate in the second quarter of 2018, leading some to wrongly conclude rapid economic growth is here to stay. Unfortunately, this rapid growth is largely the effect of a one-time sugar high and is not representative of likely growth over the course of the next year, let alone the next decade. Most analysts continue to estimate that real GDP will grow by about 3 percent this year and by 2 percent or less annually over the next decade.

In remarks, President Donald Trump was among those that labeled the high growth numbers as "very, very sustainable," saying "this isn’t a one-time shot." White House National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow made similar remarks. These statements are false and draw the wrong conclusion from this short-term growth boost.

Rapid Growth Comes From a One-Time Boost

As we explain in our paper, Can America Sustain the Recent Economic Boost?, economists have long expected strong growth this year as the economy completes its recovery from the Great Recession. That one-time boost is being further assisted from the temporary stimulative effects of recent tax cuts and spending increases, as well as timing shifts of certain economic activities.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently estimated that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would boost the 2018 economy by about 0.3 percentage points, and the 13 percent discretionary spending increase from the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 and FY 2018 omnibus spending bill would have a similar effect. Most of this growth comes from the one-time surge in consumption that accompanies deficit-financed legislation. We recently estimated that other deficit-financed bills would generate a further 0.2 percent of growth.

At the same time, many analysts believe the second-quarter growth numbers are artificially inflated by shifts in consumption to avoid the new tariffs announced this quarter. Most significantly, China appears to have accelerated purchases of soybeans, crude oil, and other exports before new tariffs went into effect. Pantheon Macroeconomics estimated the soybean surge alone could account for as much 0.6 percentage points of the growth rate. These accelerated purchases mean faster growth now at the expense of slower growth later.

Assuming CBO's numbers apply evenly on a quarterly basis and Pantheon's numbers are correct, these temporary factors alone account for 1.4 percentage points of annual growth – meaning without them the second-quarter growth rate would fall to 2.7 percent. Even this 2.7 percent figure is likely inflated by the accelerated export of other goods, as well as one-time recovery effects.

Rapid Second Quarter Growth Won't Last Through 2018

Growth of 4.1 percent is a fast quarterly growth rate, the highest since the third quarter of 2014 (4.9 percent). Nevertheless, it’s notable that this growth rate is based on several temporary and predictable factors. But importantly, growth often fluctuates quarter to quarter – and over the course of the year, economic growth is likely to be significant slower.

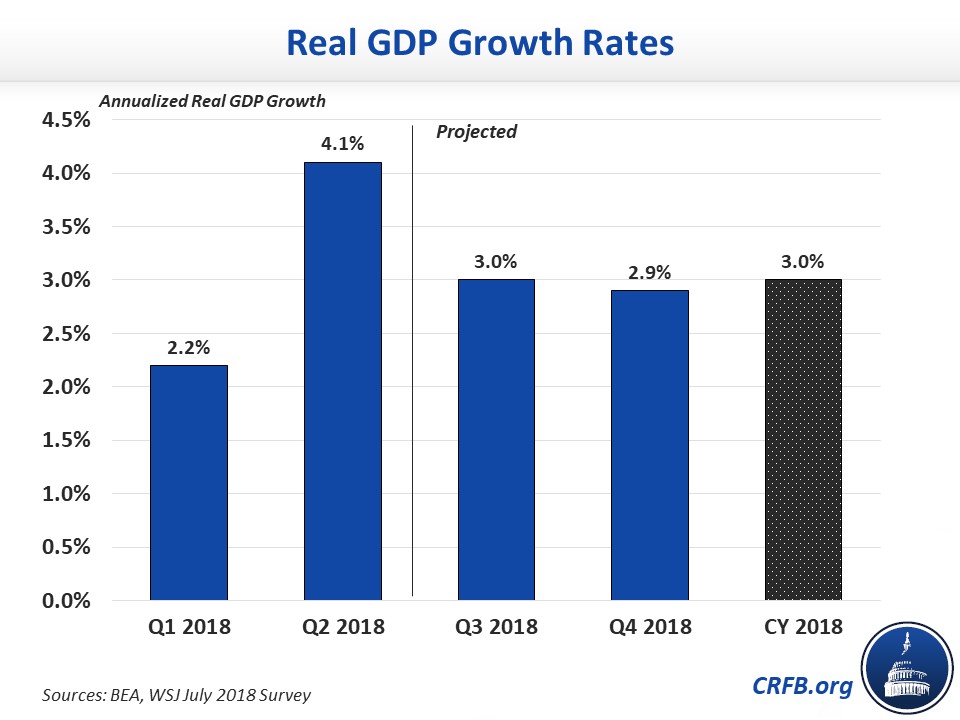

In the first quarter of 2018, the U.S. economy grew by 2.2 percent, a lower number that would be included in an annual average. Meanwhile, few if any forecasters project last quarter's rapid growth numbers will continue in the second half of the year. For example, the average of economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal's Economic Forecasting Survey projected an annualized growth rate of 4.1 percent in the second quarter, but it also projected 3.0 percent in the third quarter and 2.9 percent in the fourth.

Assuming the survey's projections come to pass, these growth rates would lead to average growth of about 3.0 percent in 2018. That rate is in line with CBO's estimate of 3.0 percent growth and the Federal Reserve's estimate of 2.7 percent (Q4/Q4).

Three percent growth is still quite high given current demographics, but far short of the just announced 4.1 percent advanced estimate for the second quarter.

Rapid Growth in 2018 Won't Last Over the Long-Term

Unfortunately, even 3 percent growth is unlikely to continue over the medium and long terms. An economy cannot operate above potential capacity indefinitely, as timing shifts and the sugar high fade. And potential GDP – which grows when people work more hours, new factories and machines and software are built, and society learns how to more efficiently produce goods and services – is limited by an aging population. As we outlined in our paper How Fast Can America Grow?, population aging means lower labor force growth, less investment, and perhaps even less productivity. As a result, nearly every forecaster projects a long-term growth rate of around 2 percent per year above inflation. The Congressional Budget Office projects a rate of 1.8 percent.

To be sure, pro-growth public policy can provide a boost. But these effects are likely to be modest. CBO has estimated the recent tax bill, for example, will increase growth by an average of 0.06 percentage points per year over the next ten years – an estimate that is in line with most other forecasts. Making the tax law more permanent and more fiscally responsible could provide a further boost, as could pursuing a variety of other policy ideas to increase labor supply, work, and investment. However, it is unlikely any combination of policies could boost long-term growth up to 3 percent per year.

The country cannot maintain its current economic sugar high. Massive borrowing can create a one-time economic surge, but it is unlikely to translate into a sustained improvement in growth as it is not growing potential GDP. Quite the opposite, high and rising debt is likely to stunt long-term economic growth by reducing productive investment.

The country should adopt pro-growth policies whenever sensible but be realistic about the structural challenges constraining growth. BEA's estimate of economic growth does nothing to change those challenges.

Update 7/31/18: Second paragraph added to mention remarks by President Donald Trump and White House National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow that were given shortly after our publication.