How Much Will Trump's Tax Plan Cost?

The White House released principles and a framework for tax reform today. We applaud the President's focus on tax reform, but the plan includes far more detail on how the Administration would cut taxes than on how they would pay for those cuts. Based on what we know so far, the plan could cost $3 to $7 trillion over a decade– our base-case estimate is $5.5 trillion in revenue loss over a decade. Without adequate offsets, tax reform could drive up the federal debt, harming economic growth instead of boosting it.

The framework proposes a number of specific changes including: consolidating and reducing individual income tax rates to 10, 25, and 35 percent; doubling the standard deduction; cutting the business tax rate to 15 percent on both corporations and pass-through businesses; repealing the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) and estate tax; repealing the 3.8 percent investment surtax from the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"); moving to a territorial tax system; and imposing a one-time tax on money held overseas.

The plan also includes some vaguer proposals, including "providing tax relief for families with child and dependent care expenses" and eliminating "targeted tax breaks that mainly benefit the wealthiest taxpayers." Although the framework itself is vague on the latter, at their press conference Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin and National Economic Director Gary Cohn seemed to imply it meant repealing all individual deductions unrelated to savings, charitable giving, or mortgage interest (revenue would come mostly from repealing the state and local tax deduction).

Even with the detailed portions of the plan, there are not enough parameters specified to provide a certain revenue estimate of the tax plan. But making some assumptions based on prior proposals, our best rough estimate suggests the specified parts of the plan would cost $5.5 trillion. Assuming tax break limits only apply only to higher earners, that cost could be as high as $7 trillion; assuming credits and exclusions are eliminated as well as deductions, it would cost $3 trillion.

With interest costs, a $5.5 trillion tax plan would be enough to increase debt to 111 percent of Gross Domestic Product (compared to 89 percent of GDP in CBO's baseline) by 2027. That would be higher than any time in U.S. history, and no achievable amount of economic growth could finance it.

| Policy | 2027 Debt Impact | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost ($) | % of GDP | |

| Change rate structure to 10%, 25%, 35% | $1.5 trillion | 5% |

| Repeal individual AMT | $0.4 trillion | 1% |

| Repeal most deductions except for mortgages, charitable giving, and retirement | -$2.0 trillion (-$0.5 to -$4.5 trillion)* |

-7% (-2% to -16%) |

| Double the standard deduction | $1.5 trillion | 5% |

| Repeal estate tax | $0.2 trillion | 1% |

| Reduce corporate tax rate to 15% | $2.2 trillion | 8% |

| Reduce pass-through business tax rate to 15% | $1.5 trillion | 5% |

| Move to territorial system with one-time tax on overseas profits | $0** | 0% |

| Repeal the net investment income surtax | $0.2 trillion | 1% |

| Subtotal, Rough Cost of Specific Policies | $5.5 trillion ($3 to $7 trillion) |

20% |

| Repeal other tax preferences and expand child care benefits | ??? | ??? |

| Total Cost | ??? | ??? |

| Debt Impact of a $5.5 Trillion Tax Cut With Interest | $6.2 trillion | 22% |

Source: CRFB calculations based on estimates of similar policies by the Tax Policy Center and the Tax Foundation. Our estimate is very rough, as the plan lacks some details that could change the score significantly. We did not model this plan, but compiled estimates of the component pieces from various similar estimates, notably the 2016 version of Trump's campaign plan and the House GOP "Better Way." For instance, we assumed the rate structure of 10/25/35 is intended to be the same size change as the campaign proposal of 12/25/33, but the actual cost depends on the income breakpoints between brackets. Our number could be a significant understatement. Numbers may not add due to rounding.

*Range represents previous Trump proposal to limit itemized deductions, which would save $500 billion, and an aggressive approach that would eliminate most tax preferences, including exclusions and credits, would save $4.5 trillion. The base case assumes the elimination of nearly all individual deductions not related to mortgage interest, charitable giving, or savings.

**Estimate would differ based on details, but these two proposals are likely to largely offset each other.

Last week in our analysis America Needs Tax Reform, Not More Debt, we explained why a plan of this magnitude would be so problematic. Much of that discussion is included below.

Encouragingly, the Trump Administration has expressed its desire to aggressively cut many of the nation's $1.6 trillion of tax expenditures. We hope that through this process they will end up with a much more responsible and pro-growth tax reform.

America Can't Afford a $5 Trillion Tax Cut

At 77 percent of GDP, debt is currently higher than at any time in history outside of World War II and its aftermath. Even under current law, debt will rise to 89 percent of GDP by 2027. Based on the details of what has been put forward by the Trump Administration so far, debt could rise to 111 percent of GDP by 2027 – a new historical record. In dollar terms under this estimate, debt held by the public would total $31 trillion in 2027 and gross debt would total $36 trillion.

Growth Can't Pay for This Tax Cut

The Trump Administration argues that the plan will generate much faster economic growth that will offset much of the cost of the plan. However, economic studies from across the spectrum have found that deficit-financed tax cuts only pay for a fraction of their cost (including from the Congressional Budget Office and other economists). Indeed, tax reform that slows economic growth by adding too much to debt can actually cost more once economic effects are incorporated.

Even if tax cuts could generate more growth than estimated, no plausible amount of economic growth would be able to pay for a substantial portion of the tax plan, let alone reduce deficits. The country would need roughly 4.5 percent sustained growth to pay for the entire tax plan – two-and-a-half times the 1.8 percent that CBO projects to occur over the next decade. As we explained in Don't Count on 4% Growth, the last time the country achieved even 4 percent sustained growth was in the late 1960s and early 1970s (though we came close during the technological boom of the 1990s). With an aging population, those growth rates are no longer possible. Achieving just 3 percent growth would require productivity growth to rise to the record levels set in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Further, the Trump Administration and many members of Congress have talked about using economic growth to address our rising national debt. If all the gains from growth are being used to pay for tax cuts, then none can be used for deficit reduction.

In order to rely on growth to help fix the debt, any tax reform plan should be at least revenue-neutral before accounting for economic growth, so any gains from growth can be devoted to deficit reduction.

Tax Cuts Are More Effective When They are Paid For

As we explained in 5 Reasons to Pay for Tax Reform, fiscally responsible tax reform is far better for the country than debt-financed tax cuts.

For one, the country currently spends $1.6 trillion per year on tax breaks – many of which distort economic decision-making and result in a misallocation of resources. Tax reform can repeal or reform many of these tax breaks and thus improve economic efficiency. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently estimated that this effect could be significant. Though the Administration's plan does this to some extent, it could go further and in doing so also bring down the revenue loss.

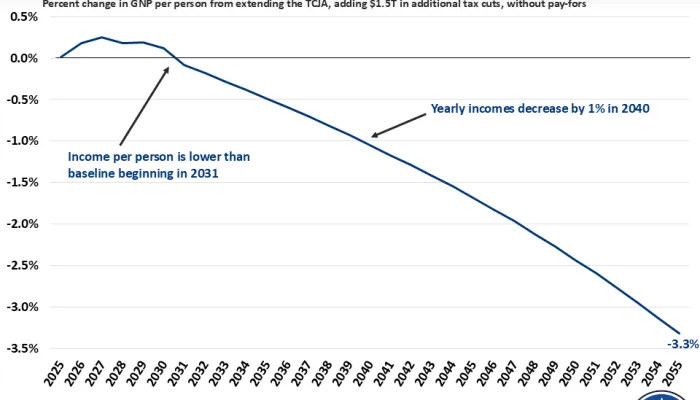

Outside of the allocative effects, debt-financed tax cuts are also generally less pro-growth than responsible tax reform. Last year, for example, the Tax Policy Center estimated President Trump's $6 trillion campaign tax plan would reduce GDP by 0.5 percent after a decade and 4 percent after two. By comparison, estimates of former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp's (R-MI) deficit-neutral tax reform from 2014 found that it would improve GDP by 0.1 to 1.6 percent after a decade.

Indeed, looking at two nearly identical tax reform packages, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in 2011 that one producing $600 billion of net revenue would generate about one-third more growth over the long run than a revenue-neutral tax reform with the same structure.

President Trump's tax reform plan still lacks important details but as it stands, the plan appears it would add significantly to the debt. Tax reform is an important part of any economic growth strategy. But expecting massive unprecedented economic gains from any tax reform is unrealistic; especially from one that is deficit-financed.

As the Trump Administration works with Congress to add more details to this plan, we hope they make it much more fiscally responsible and that they couple it with the important spending and entitlement reforms necessary to put the country on a sustainable fiscal path.