Is the Fed Buying Our New Debt?

So far, the legislative response to the COVID-19 pandemic has injected around $1.5 trillion of fiscal support into the economy. In combination with underlying structural deficits and economic feedback (mainly lost revenue) from the economic crisis, actions taken so far will lead to roughly $4 trillion of borrowing in fiscal 2020 alone — four times as much as in fiscal year 2019. Just last week, the Treasury announced it will be borrowing $3 trillion in this quarter — the equivalent of $1 trillion per month and over five times the previous record of $569 billion set in the fourth quarter of 2008. But where will the money come from? Who will finance all this new debt?

In a COVID Money Tracker webinar today, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget's Marc Goldwein tried to answer that question. His slide deck is available here and a video of his webinar here. The short answer: the Federal Reserve has indirectly bought the vast majority of debt issued since the crisis began. Whether this is debt monetization or more conventional quantitative easing is up for debate.

This blog post is a product of the COVID Money Tracker, a new initiative of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget focused on identifying and tracking the disbursement of the trillions being poured into the economy to combat the crisis through legislative, administrative, and Federal Reserve actions.

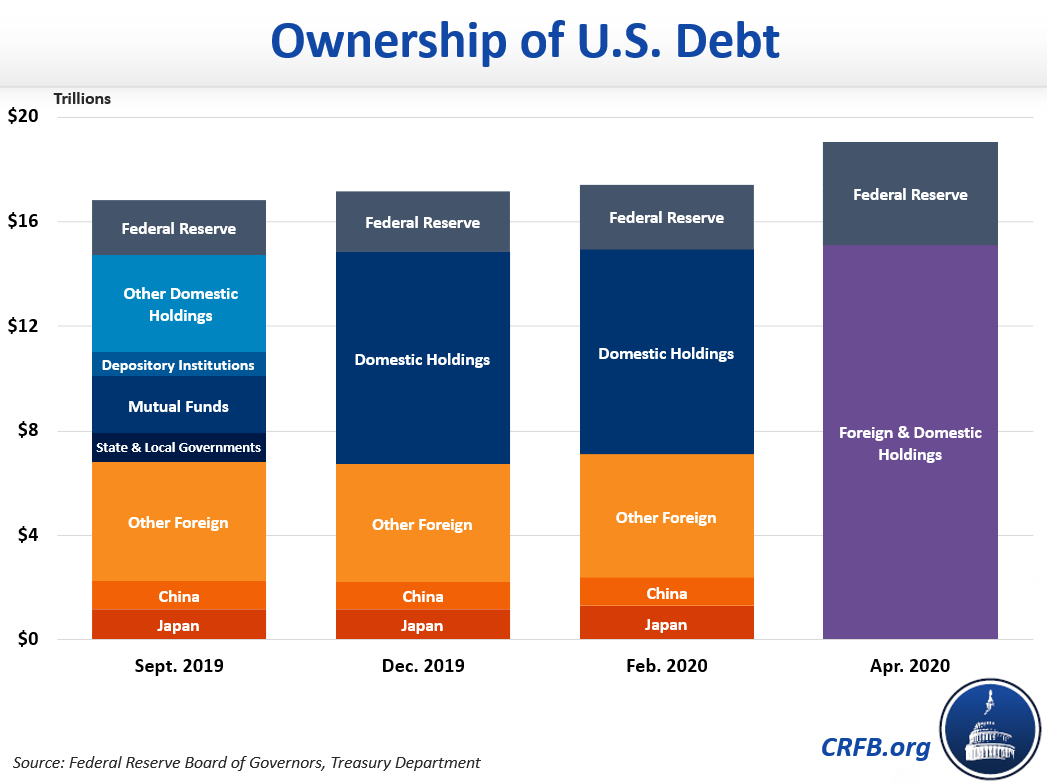

When the federal government runs deficits, it must sell bonds in order finance its borrowing. The plurality of these bonds (almost half in September of 2019) are held domestically by mutual funds, pensions, banks, state and local governments, private businesses, and individual bondholders. Most of the remaining bonds (40 percent in September of 2019) are held by foreign companies, individuals, investment portfolios, central banks, and governments — China and Japan are the largest foreign holders of U.S. Treasuries, each holding about 7 percent. The remaining debt (13 percent in September of 2019) is held by the Federal Reserve — the central bank of the United States.

Since the crisis began, neither domestic nor foreign holdings of debt have increased significantly. Instead, the Federal Reserve has sharply increased its ownership of U.S. debt.

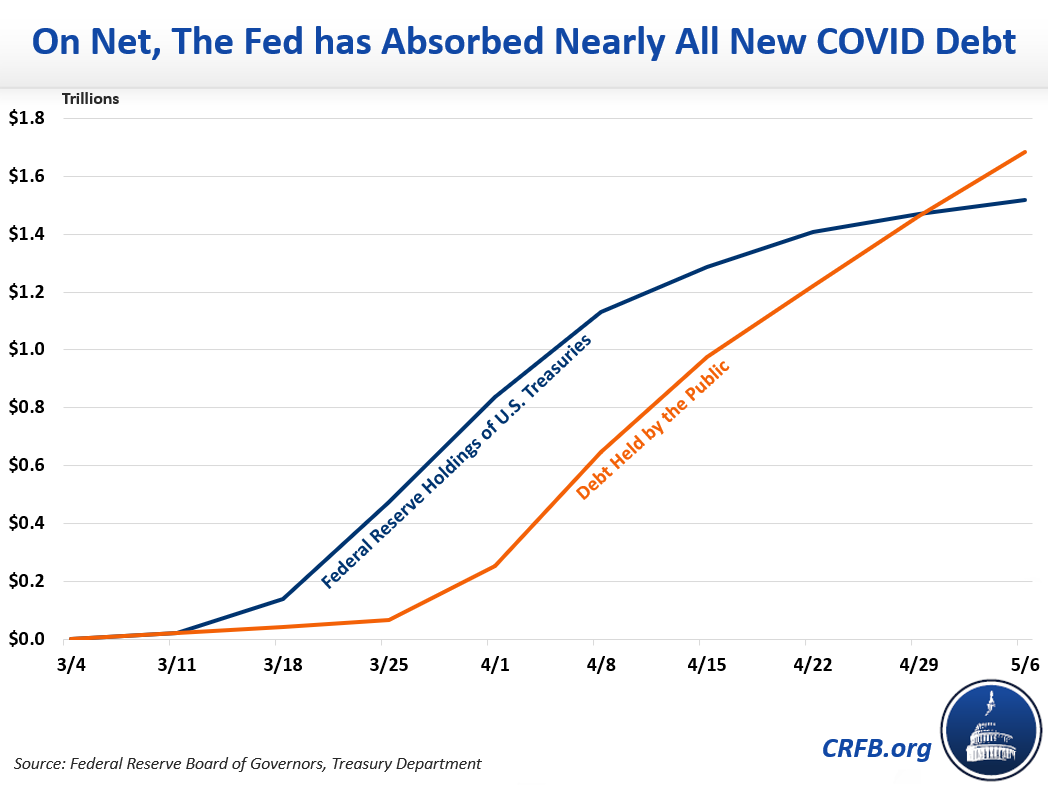

In fact, the Federal Reserve has indirectly purchased nearly all new debt issued since the recent crisis began. Since the signing of the first coronavirus response bill into law on March 4, debt held by the public has increased by $1.68 trillion while Federal Reserve holdings of Treasury bonds have increased by $1.52 trillion.

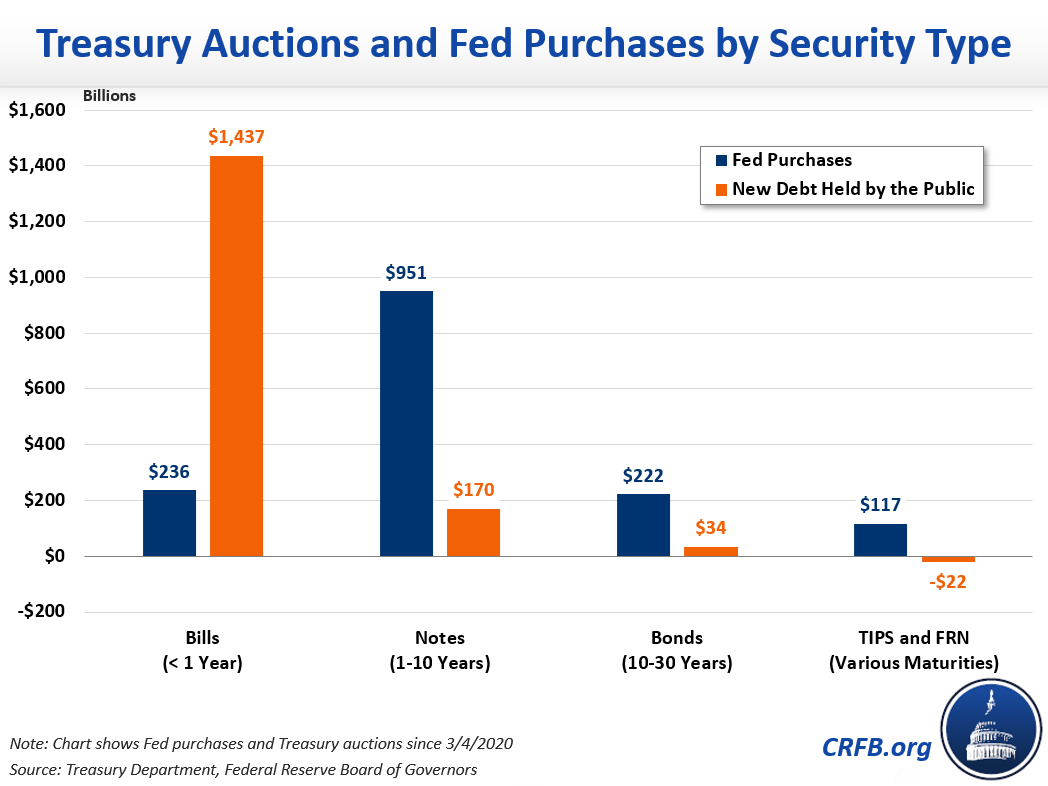

In practice, the Federal Reserve does not directly buy debt from the Federal Government — it only buys from so-called primary dealers. Instead, private actors buy federal debt at auction from the Treasury Department while the Federal Reserve simultaneously purchases debt from the private sector.

For the most part, the Federal Reserve is not even buying the same kind of debt as the Treasury is selling. Issuances have been largely for short-term notes and bills, whereas the Federal Reserve has mostly been purchasing medium-term notes and long-term bonds.

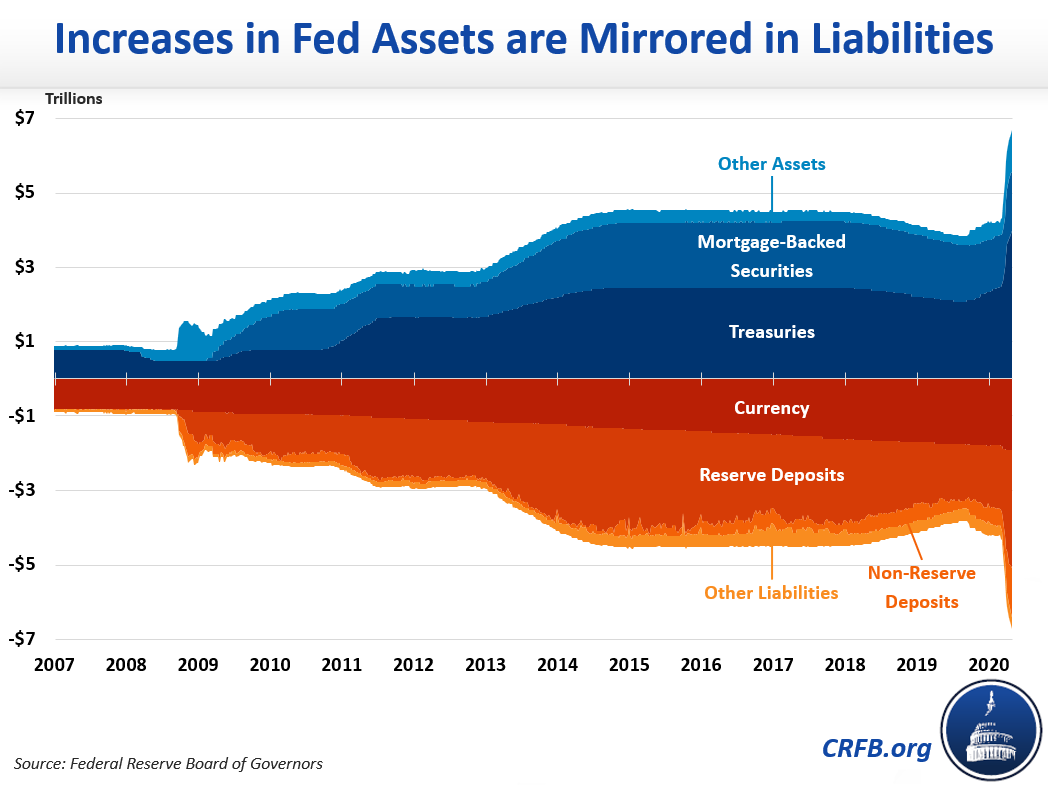

Whether this represents "monetization" is a topic of great debate. The Federal Reserve does not appear to be expanding currency at an accelerated rate, but it is dramatically expanding "reserve deposits," digital money held on behalf of private banks to allow them to expand their lending. On the other hand, its purchases of Treasuries, Mortgage-Backed Securities, and other assets are part of a broader strategy for quantitative easing and market stabilization. So far, the Fed has committed to as much as $5.5 trillion and disbursed over $2.0 trillion to support the economy.

It also is not clear whether the Federal Reserve will continue to buy federal debt at the pace it is being issued. When they began their most recent bond-buying program, the Federal Reserve was purchasing $75 billion of bonds per day; now it is purchasing $35 billion per week.

Yet even just the commitment to engage in as much bond-buying is needed to stabilize the market sends a message to the market that the central bank is willing to supplement demand for Treasuries as long as is needed, making it difficult for investors to punish the United States for fiscal largesse.

Regardless of who is buying our debt, it is growing rapidly and will soon reach record levels as a share of the economy. After this crisis is over, lawmakers will also have to consider the reality that the Federal Reserve will eventually begin to wind down its balance sheet once again, removing the central bank cushion and heightened demand for U.S. debt. Setting the nation down a path toward fiscal sustainability will therefore be crucial in the months and years to come.