After Tax Reform, Tax Expenditures Remain Costly

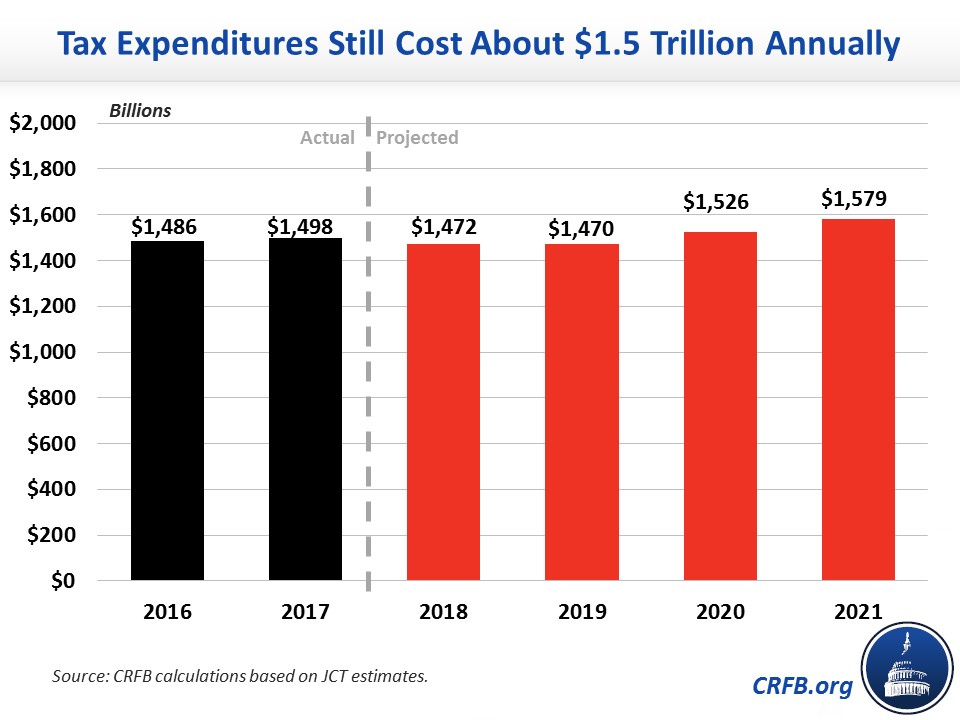

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently released its latest tax expenditure estimates. The report shows that despite the 2017 tax law, which was billed as an effort to reduce tax breaks, tax expenditures will continue to cost $1.5 trillion per year.

Specifically, the individual and corporate income tax expenditures sum to $1.47 trillion in 2018 and 2019, compared to $1.49 trillion in 2016 and $1.50 trillion in 2017. In other words, the tax bill kept the cost of tax breaks from rising in the short term but did too little base broadening to reduce their cost relative to prior years.

A main goal of tax reform was supposed to be to eliminate tax preferences. This goal was central to prior tax reform plans, including from the Tax Reform Panel in 2005, the Simpson-Bowles commission in 2010, and former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp's (R-MI) Tax Reform Act of 2014.

The original House Better Way tax plan from 2016 called for repealing all itemized deductions other than for charitable giving and mortgage interest, reforming many of the largest tax preferences, and repealing most "special interest" exemptions, deductions, and credits on the individual and business side. More recently, the final 2017 tax law has been touted as "eliminating costly special-interest tax breaks."

Yet a quick survey of JCT's tax expenditure report makes clear that only one major tax expenditure was repealed – the Domestic Production Activities Deduction (Section 199). To be sure, other tax preferences, such as the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, morgage interest deduction, and the orphan drug tax credit, were scaled back. But the legislation also expanded tax breaks – for example, the child tax credit and expensing of equipment. And it created new tax breaks, the largest being a 20 percent deduction for pass-through business income.

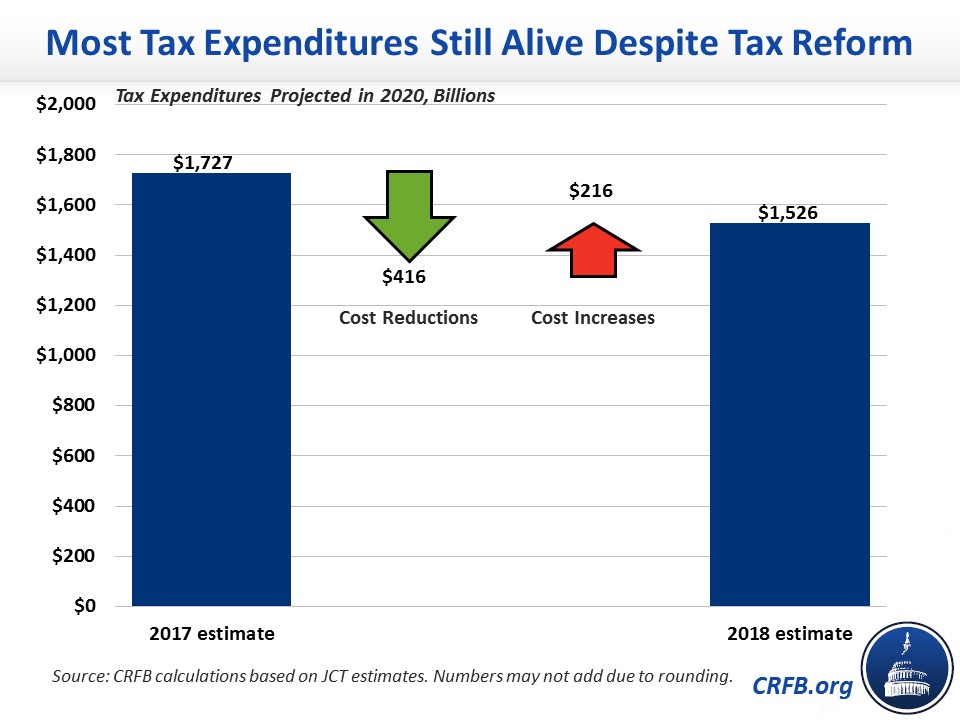

On net, the cost of tax expenditures is lower than it otherwise would be absent the law. The combined cost of tax breaks in 2020 will total about $1.53 trillion under JCT's current estimates, compared to $1.73 trillion under JCT's prior projections. The lower cost is driven by roughly $415 billion of reductions in cost of tax expenditures – largely a direct or indirect* result of the 2017 tax law – partially offset by $215 billion of increased costs.

Importantly, these numbers include some reductions to non-tax expenditure base provisions, which JCT views as "negative tax expenditures." But it excludes other reductions to those provisions – like the elimination of dependent exemptions in favor of a larger child tax credit and a non-child dependent credit – which also broaden the base (it also excludes the expanded standard deduction, which narrows the tax base).+

Still, JCT's estimates make clear that the 2017 tax law did relatively little to reduce tax breaks, and most tax expenditures continue to remain available for lawmakers to repeal or reform. Any further action on tax reform should focus on just that.

*For example, the value of the charitable deduction falls as a result of more individuals opting for the larger standard deduction, and the values of nearly all deductions and exclusions fall due to lower rates.

+If the child tax credit were removed for purposes of parity, the 2020 value of tax expenditures would have declined from $1.67 trillion in last year's estimates to $1.4 trillion this year.