The Affordable Care Act and the HI Trust Fund

Update: Charles Blahous has posted a response to his critics here.

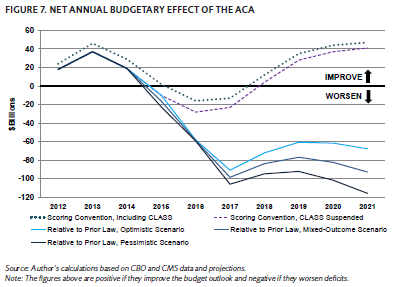

Charles Blahous, a Social Security and Medicare Trustee, has released a new report on the Affordable Care Act that has made some waves. The study claims that ACA will increase--rather than reduce--deficits by anywhere from $346 billion to $527 billion from 2012-2021. By contrast, CBO estimated that the bill would reduce deficits by $210 billion from 2012-2021 in their most recent comprehensive estimate.

The differences come from numerous sources. First, taking out the CLASS Act reduces revenue by about $85 billion. Second, Blahous uses different assumptions that could result in larger costs or fewer savings (these assumptions are why there is a range on his estimates). He surmises that: the exchange subsidies could be more expensive due to higher enrollment from employers dropping coverage or Congress increasing their growth rate; the mandated IPAB savings could be greater than zero and be overridden; the health insurance excise tax thresholds will be indexed to a higher growth rate, thus limiting their reach; and the thresholds for the new HI taxes would be indexed to keep the revenue at a constant percent of GDP, rather than not be indexed at all.

However, the biggest difference stems from how he treats the Medicare savings. Under current projections, the savings would total $850 billion from 2012-2021 and extend the life of the HI Trust Fund from 2016 to 2024. Of course, as we have said before, it's a rhetorical fallacy to say that these savings can both be used as offsets and to extend HI solvency. Blahous takes this a step further by arguing that most of these savings aren't actually savings, since when the HI Trust Fund runs out in 2016, spending would automatically have to be cut. CBO does not account for this fact, instead assuming that Medicare spending continues as scheduled. When you take out the savings that would have had to happen anyway, it reduces the amount of Medicare savings by $470 billion. In other words, he assumes $470 billion of Medicare cuts would already take place.

Is this a correct way of accounting? In a technical sense, yes, since the trust fund legally cannot pay out more in benefits than it takes in or otherwise has in reserve. However, this is not the way that conventional scoring from CBO would view it. The difference from CBO is one of baselines: in Blahous's baseline, deficits are lower than in CBO's baseline and the ACA raises them to CBO levels. Of course, using this method would require one to apply this to other trust funds whose solvency is projected to expire within the ten-year window (disability insurance, for example) and would further lower baseline deficits; in addition, the long-term outlook would change if you account for Social Security benefits being reduced in 2036 and beyond.

As you can see below, current law debt is lowered significantly if you take into account the insolvency of the Social Security Disability Trust Fund, the Highway Trust Fund, the HI Trust Fund, and the Social Security Old Age and Survivors Trust Fund.

But if you break away from trust fund accounting and use a unified budget perspective in which benefit levels are fully funded, this last point really doesn't change the estimate of the Affordable Care Act. The other points--about whether certain aspects of the law will go forward as scheduled--are more relevant when using this perspective. The difference between the current law assumptions and his most pessimistic assumptions is about $180 billion. If you take those pessimistic assumptions, add them to the most recent budget impact projection and take out the CLASS Act, the ACA would increase deficits by as much as $55 billion through 2021. Using his "mixed-outcome" scenario, which splits the difference between current law and the pessimistic scenario, the ACA would reduce deficits by about $30 billion through 2021. Still, these alternative scenarios are not true estimates, but the effect of ACA assuming that future Congresses undo the cost-constraining or cost-controlling aspects of the law that may be politically difficult to sustain.

In short, the Affordable Care Act can only extend the life of the HI Trust Fund to the extent that it does not offset the coverage expansions in the law (or vice versa). At the same time, one cannot claim that repealing the Affordable Care Act would reduce the deficit while saying that it would not shorten the life of the trust fund. We'll get into more details about Blahous's points in a blog soon.