Primer: Understanding the Tax Gap

One of the most fair and efficient ways for policymakers to raise revenue would be to close some portion of the “tax gap.” The tax gap is the difference between taxes paid and taxes owed by law. In this primer, we answer the following questions:

- How Big is the Tax Gap?

- Why Is There a Tax Gap?

- Which Unpaid Taxes Contribute to the Tax Gap?

- Who Contributes to the Tax Gap?

Reducing the tax gap could raise additional revenue without increasing taxes and should be a key legislative priority for both parties. In future pieces, we will discuss ideas and options for how to close it.

How Big is the Tax Gap?

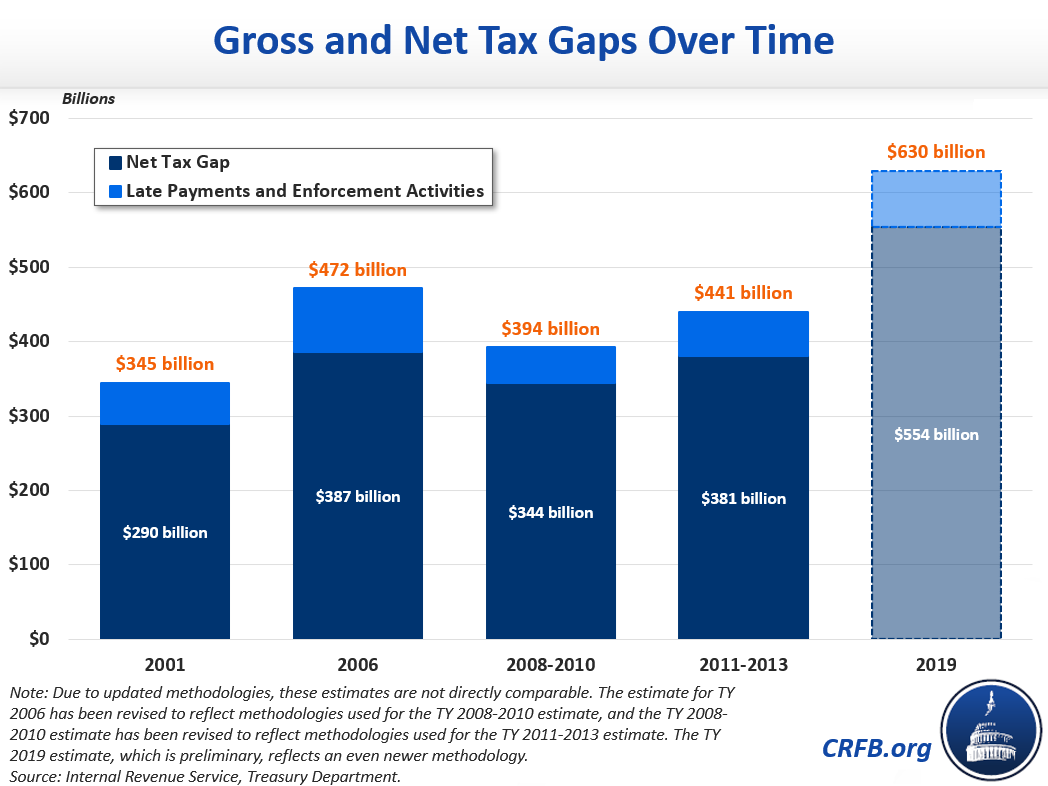

The Department of the Treasury recently estimated a "gross tax gap" of $630 billion in tax year 2019, with over $3.6 trillion of taxes owed but only about $3 trillion paid voluntarily. After accounting for $76 billion of additional revenue from Internal Revenue Service (IRS) enforcement activities and late payments, Treasury estimates the “net tax gap” totaled $554 billion in 2019, which is 2.6 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), or 15.2 percent of total tax revenue owed.

Treasury’s estimate is based on a more detailed analysis published by the IRS in 2019, covering tax years 2011 through 2013. Over that period, the IRS estimated the gross tax gap averaged $441 billion per year, while the net tax gap averaged $381 billion.

The more recent estimate also incorporates additional underreporting of offshore wealth and pass-through entities not captured in the IRS’s 2011-2013 estimate. This additional underreporting added $46 billion to the estimate for tax year 2019 and would have added $33 billion per year to the 2011-2013 estimate. However, none of these estimates include non-filing of corporate income taxes, which the IRS has never been able to accurately estimate. Furthermore, none of these estimates account for contributions to the tax gap from sources of income that have emerged more widespread since 2011, such as work and transactions in the gig economy or through cryptocurrency.

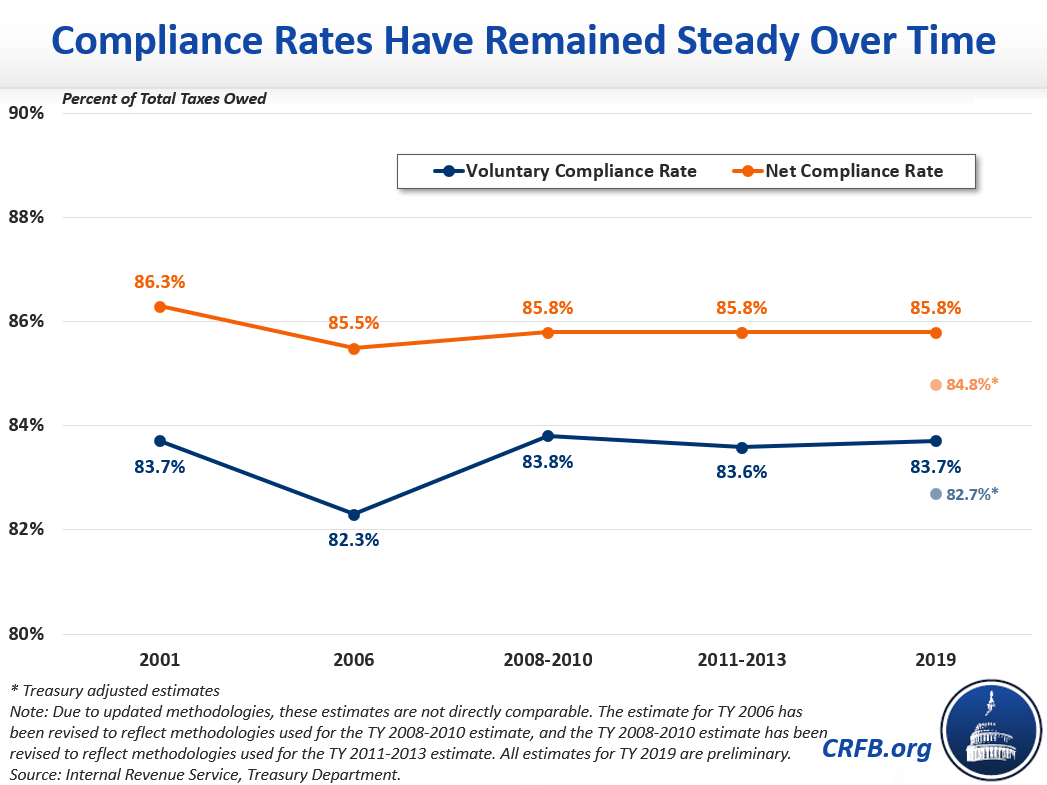

One way to measure the size of the tax gap is as a share of total taxes owed. The Voluntary Compliance Rate (VCR) describes what share of taxes is paid voluntarily (corresponding to the gross tax gap), while the Net Compliance Rate (NCR) describes the share of taxes ultimately paid (corresponding to the net tax gap).

The IRS recently estimated the average VCR was 83.6 percent from 2011 through 2013, while the average NCR was 85.8 percent – meaning enforcement has only increased compliance by two percentage points and 14 percent of taxes owed remain uncollected. These compliance rates are roughly in line with previous IRS tax gap analyses covering tax years 2001, 2006, and 2008 through 2010 – though the VCR dipped to 82.3 percent in 2006.

Importantly, the figures above may be in some ways incomplete. Incorporating certain offshore funds, Treasury estimates the tax year 2019 VCR was 82.7 percent and the 2019 NCR was 84.8 percent – meaning more than 15 percent of taxes remain uncollected.

The process of estimating the tax gap is extremely complex and time consuming, which is why official analyses are published by the IRS only periodically and feature data that lag several years behind. However, the IRS is currently developing a new methodology that will produce more accurate, comprehensive, and timely estimates of the tax gap. According to testimony submitted by the IRS to the Senate Finance Committee, applying this new methodology to its official estimates of the tax gap from 2011-2013 suggests that the gross tax gap for tax year 2019 was approximately $600 billion, which is consistent with Treasury’s recent estimates.

Others have estimated the tax gap could be even larger. In a 2019 paper, economists Larry Summers and Natasha Sarin estimated that the gross tax gap would be approximately $630 billion in 2020 and would total approximately $7.5 trillion from 2020 through 2029. During a recent Senate Finance Committee hearing, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig estimated that the true tax gap could be as large as $1 trillion per year if newer and more elusive sources of income were included, such as trading in cryptocurrencies, foreign-sourced income, and business income improperly passed through as individual income.

Why Is There a Tax Gap?

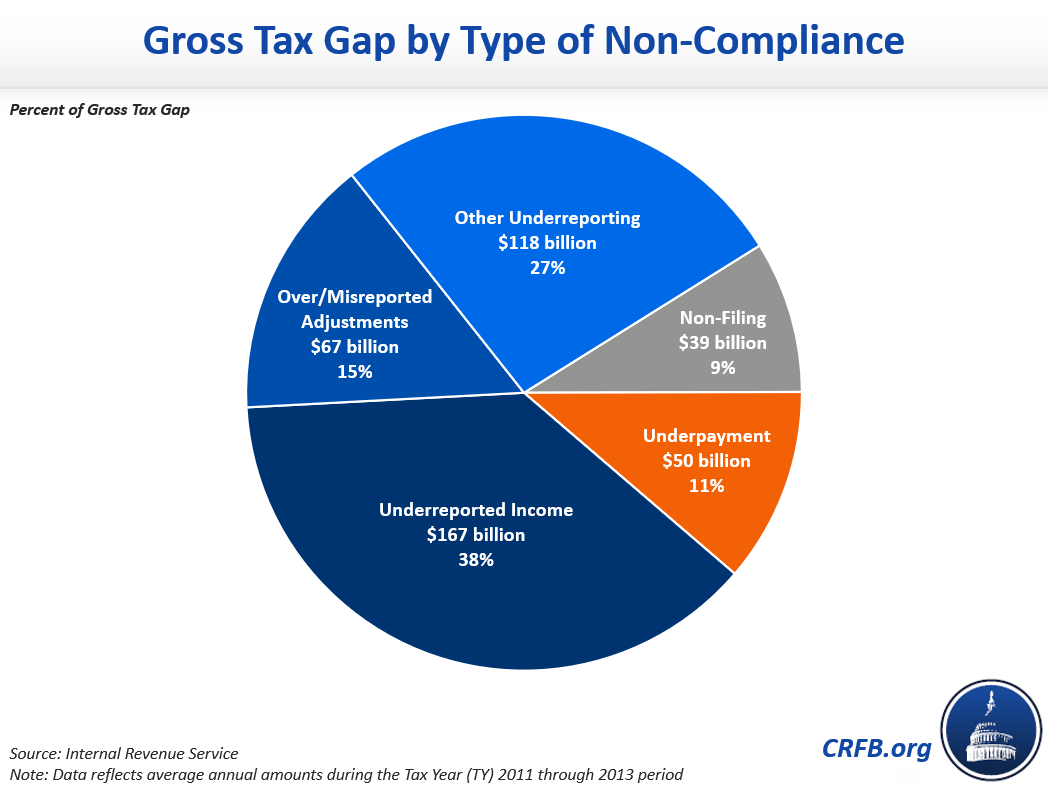

Taxes are underpaid for one of three reasons – either tax returns are never filed, taxes owed are underreported, or taxes are accurately reported but underpaid.

According to IRS data, 9 percent of the gross tax gap comes from non-filing, 11 percent from underpayment, and 80 percent from underreporting – with at least 38 percent due to underreporting of income and at least 15 percent due to over-reporting or misreporting of adjustments (the remaining 27 percent is not defined).

Non-filing occurs when an individual or business that earned taxable income and should have filed a tax return with the IRS fails to do so. For the 2011-2013 period, the non-filing gap averaged $39 billion per year, or 9 percent of the annual gross tax gap, with the vast majority coming from individual income tax filers.1

Underpayment occurs when an individual or business that did file a tax return with the IRS fails to pay all the taxes it owes on that return. For the 2011-2013 period, the underpayment gap averaged $50 billion per year, or 11 percent of the annual gross tax gap. Again, the vast majority of this gap comes from individual income tax filers.2

By far the biggest contributor to tax gap is underreporting, or when an individual or business files a tax return that incorrectly underreports the taxes it owes in a given year. For the 2011-2013 period, the underreporting gap averaged $352 billion per year, or 80 percent of the annual gross tax gap.

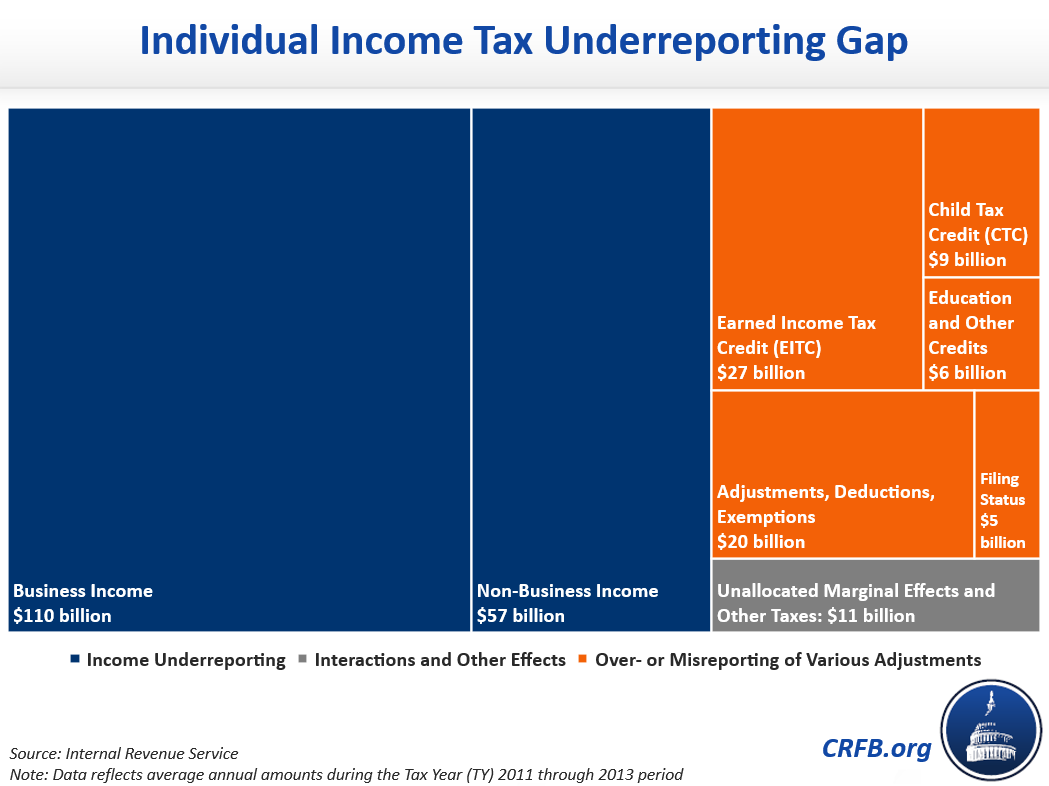

Of the $352 billion in estimated underreporting, $245 billion comes from individual income taxes, $69 billion from payroll taxes, $37 billion from corporate income taxes, and $1 billion from the estate tax.

Over two-thirds of individual underreporting comes from underreporting of income – $110 billion from business income and $57 billion from non-business income – and more than a quarter comes from over-reporting or misreporting of various adjustments (the rest comes from interactions and other effects).

Of the $67 billion that comes from over- or misreporting of various adjustments, $27 billion comes from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); $9 billion comes from the Child Tax Credit (CTC); $6 billion comes from education-related and other tax credits; $5 billion comes from misreporting of filing status; and the remaining $20 billion comes from other deductions, exemptions, and adjustments.3

Which Unpaid Taxes Contribute to the Tax Gap?

Overall, approximately 71 percent of the gross tax gap comes from the individual income tax, 18 percent comes from payroll taxes, and nearly 11 percent comes from the corporate income tax and other taxes.

In the 2011-2013 period, the individual income tax accounted for $314 billion, or 71 percent, of the $441 billion annual gross tax gap. After accounting for $43 billion from late payments and enforcement, individual income taxes accounted for $271 billion of the $381 billion net tax gap.

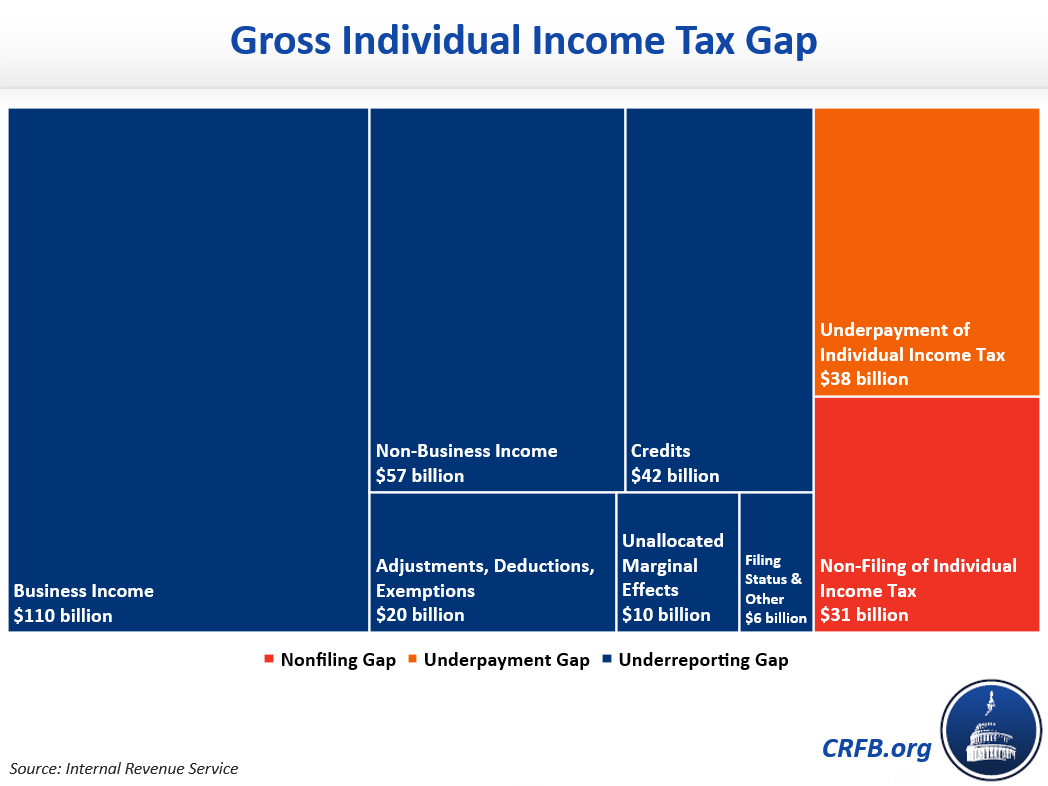

Of the $314 billion gross individual income tax gap, $31 billion was due to non-filing (about 10 percent), $38 billion was due to underpayment (about 12 percent), and $245 billion was due to underreporting (about 78 percent). Within that $245 billion of underreporting, $110 billion – nearly half – was attributable to taxes on “pass-through” business income. Another $57 billion came from non-business income; $42 billion from overpayment of credits; $20 billion from awarded adjustments, deductions, and exemptions; and $16 billion from incorrect filing statuses, other taxes, and unallocated marginal effects.

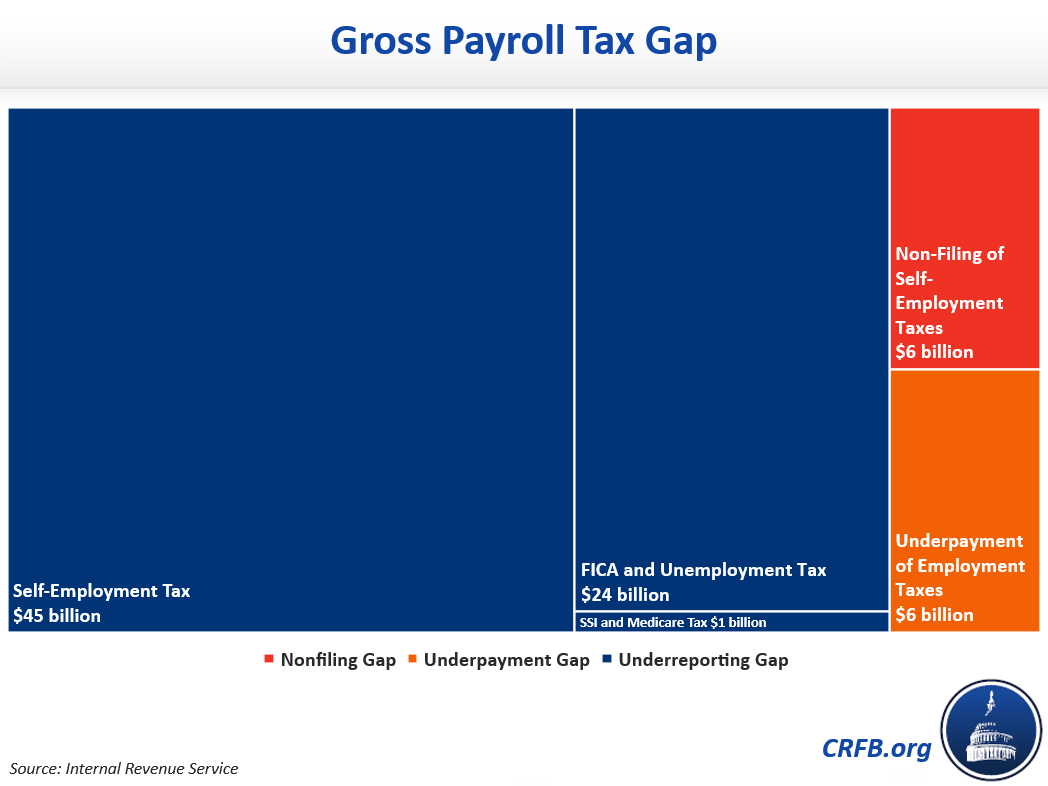

Unpaid payroll taxes account for $81 billion of the gross tax gap, or $77 billion of the net tax gap. Of the gross amount, $6 billion was due to non-filing (over 7 percent), another $6 billion was due to underpayment (over 7 percent), and $69 billion was due to underreporting (over 85 percent).

Most payroll taxes that went unpaid from 2011-2013 – including $45 billion from underpayments and $6 billion from non-filing – came from self-employment taxes paid by small business owners, sole proprietors, and independent contractors. Underreported and underpaid employee and employer payroll taxes made up another $25 billion and $6 billion, respectively

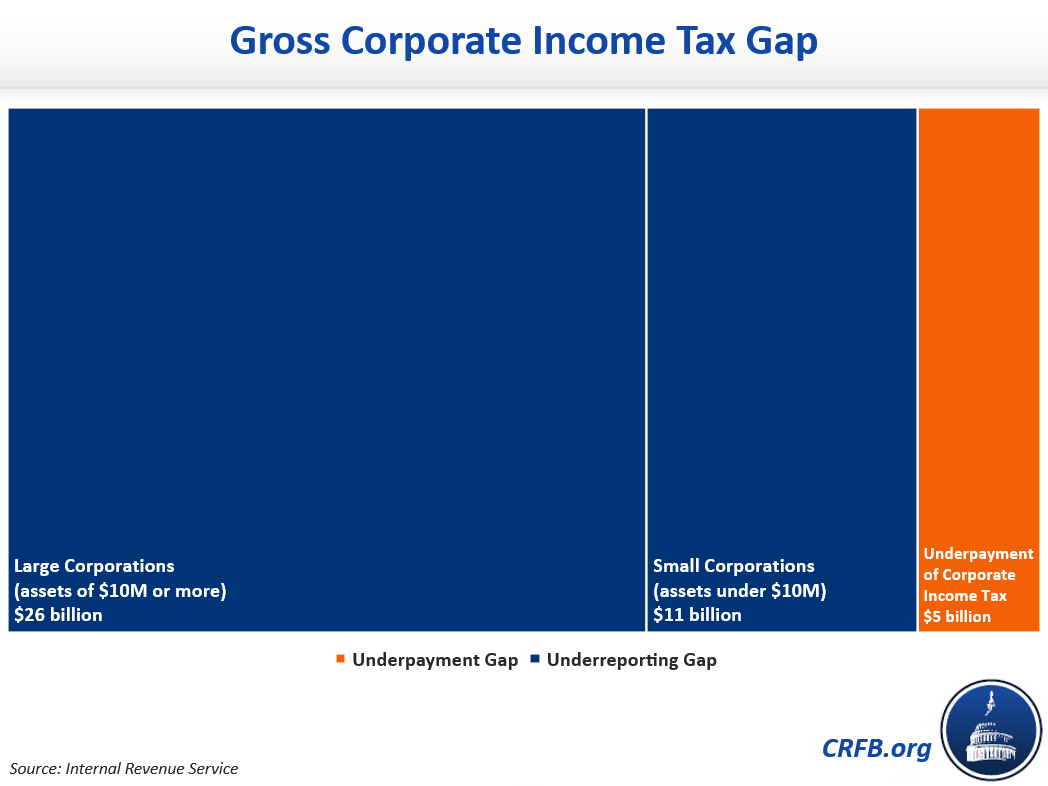

Meanwhile, the corporate income tax accounted for $42 billion of the gross tax gap, or $32 billion of the net tax gap after $10 billion of late and recovered payments.

This gross figure includes $5 billion due to underpayment (about 12 percent) and $37 billion due to underreporting (about 88 percent). The IRS breaks this number down further into underreporting of corporate income taxes from “small corporations” with assets of less than $10 million and underreporting of corporate income taxes from “large corporations” with assets of $10 million or more, which accounted for $11 billion and $26 billion, respectively.

Because the IRS currently lacks an accurate method for estimating unpaid taxes due to non-filing of corporate income tax returns, the actual figures may differ significantly.

Finally, a very small part of the overall gross tax gap comes from unpaid estate taxes and, to a much lesser extent, unpaid excise taxes. In 2011-2013, unpaid estate taxes contributed approximately $3 billion per year to the annual gross tax gap, or less than 1 percent. Unlike most other categories of tax, most unpaid estate taxes are due to non-filing, representing $2 billion per year. Another $1 billion per year in unpaid estate taxes come from underreporting, and less than $500 million comes from underpayment. Underpaid excise taxes represent less than $500 million annually.

Also, unlike most other categories of tax, the majority of estate taxes that were not paid in a timely manner – 55 percent or an average of $2 billion per year – were eventually collected through late payments or enforcement activities. This means that just over $1 billion (less than one half of one percent) of the $381 billion annual net tax gap from 2011-2013 came from estate taxes. The net tax gap attributable to unpaid excise taxes averaged less than $500 million per year during that period.

Who Contributes to the Tax Gap?

Most of the gross tax gap – 58 percent by our estimate – comes from unpaid or underpaid business and self-employment income taxes, the vast majority of which (49 percent of the total gross tax gap) comes from pass-through entities such as sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations.

We estimate only 18 percent of the tax gap comes from taxation of wages, salaries, government benefits, and other ordinary income, even though this category covers the majority of taxable income and taxes paid.

Another 15 percent of the tax gap comes from credits, deductions, filing status, and other adjustments, and about 9 percent comes from unpaid or underpaid taxes on capital income.

| Individual Income Tax | Payroll Tax | Corporate and Other Taxes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business and Self-Employment Income | 36% | 12% | 10% | 58% |

| Labor and Other Income | 12% | 6% | - | 18% |

| Credits, Deductions, and Adjustments | 15% | - | - | 15% |

| Capital Income | 8% | - | <1% | 9% |

| Total | 71% | 18% | 11% |

Source: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, based on IRS Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2011-2013

That so much of the tax gap comes from business income – and pass-through income in particular – is a consequence of the way these entities report their taxes. While taxes are withheld from wages when they are paid and are at least reported for most other types of ordinary and capital income, business income (and especially self-employment income) is effectively reported on a voluntary basis with little, if any, third-party verification.

As an example, the IRS estimates wages and salaries have a one percent misreporting rate, while sole-proprietor business income has a misreporting rate closer to 60 percent.

* * * * *

The federal government loses well over $500 billion per year from unpaid taxes. Four-fifths of those unpaid taxes are due to underreporting, more than two-thirds are individual income taxes and three-fifths come from business and self-employment income, mainly from self-employed workers and pass-through entities. The vast majority of the tax gap is associated with income or tax breaks where there is no withholding and little information reporting.

Policymakers should work together to enact legislation to reduce the tax gap and improve tax compliance.

1 To measure the non-filing tax gap, the IRS first identifies all individuals who did not appear as primary or secondary taxpayers on a timely or late-filed return (using a process it calls the Administrative Data Method), then assembles comprehensive data for these individuals from third-party reporters. It then assigns these individuals to hypothetical tax units, which are stratified to correspond with aggregate income distributions observed in Census data. Finally, the IRS estimates the tax liability of those non-filers who likely did earn taxable income and subtracts from that an estimate of the tax those individuals likely did pay through withholding and other means.

2 Of the three types of noncompliance, underpayment is by far the easiest for the IRS to estimate because all the income in question has already been made visible to the IRS through filed tax returns. To measure the underpayment gap, the IRS simply calculates the difference between the amount of taxes owed as reported on returns and the amount of taxes paid on time.

3 The underreporting gap is the most difficult of the three to estimate. The IRS primarily relies upon actual audit data taken from a stratified, random statistical sample of tax returns performed under a program called the National Research Program (NRP). Unlike typical compliance or risk-based audits, NRP audits are broad in scope and meant to glean as much information as possible, which then helps inform the IRS’s risk-based audit selection tools and other compliance efforts.