Was the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Tightening Unprecedented?

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, House Ways and Means Committee Ranking Member Kevin Brady (R-TX) and former National Economic Council director Larry Lindsey argue that the 2017 tax law will produce a sustained increase in economic growth rather than a sugar high, and they criticize the Federal Reserve for taking unprecedented action to undermine the economy in response to the tax cuts.

While reasonable people can disagree on the merits of recent Federal Reserve tightening, it is far from unprecedented. We rate this claim as misleading.

In arguing against Fed actions, Brady and Lindsey say that "From December 2017 to 2018, it raised its target for the federal-funds rate by 1%, the biggest hike in any calendar year since 2005. In addition the Fed shrank its monetary base by nearly $400 billion during 2018. That is the fastest calendar-year drop in history." The authors also claimed this tightening was in response to the tax cuts.

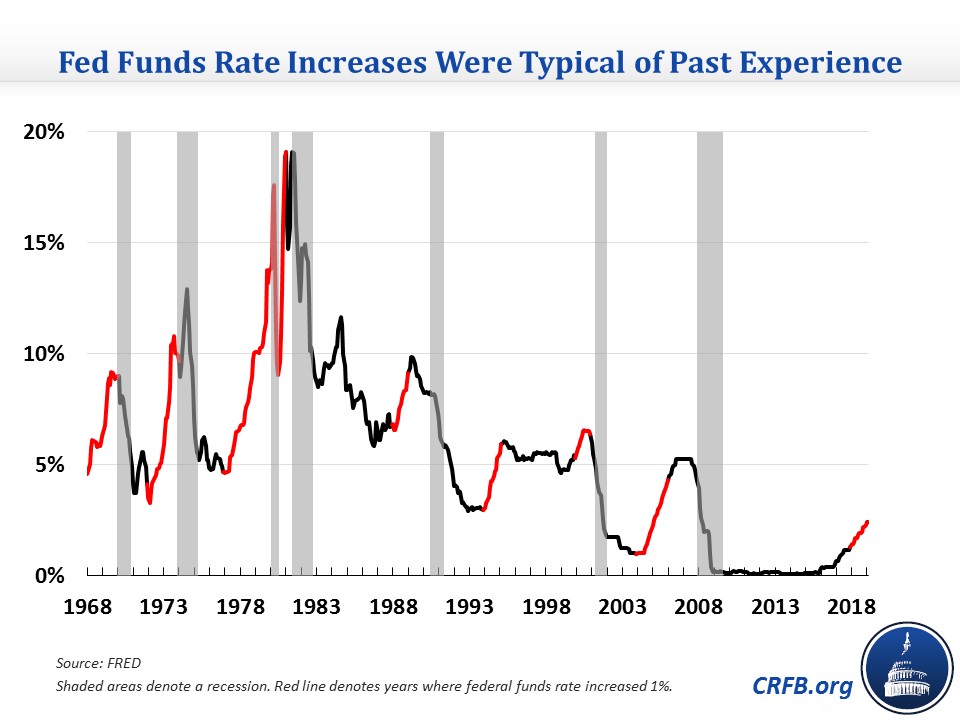

It is true the last year's increase in the federal funds rate is the largest since 2005, but that is because the mid-2000s was the last time (prior to the end of 2015) that the Federal Reserve raised rates at all. Indeed, rate hikes like those called for last year are quite common at this point in the business cycle. In the past 50 years, the 1 percentage point increase was matched or exceeded in calendar years 1968, 1969, 1972, 1973, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2004, and 2005. In many of these years, the Fed raised rates by over 2 percent.

It is also true that the Fed's balance sheet had never been reduced by $400 billion, but this too is misleading. The Fed's balance sheet has never declined by $400 billion because it has never been as large (in nominal dollars) as it was in 2017, when it held $4.5 trillion. Prior to the Great Recession, the balance sheet had never been over $900 billion in size. Relative to the size of the balance sheet, unwinding in 2018, which occurred by allowing some long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities to mature, totaled about 9 percent. Similar reductions occurred after the last major balance sheet expansion around the Great Depression and World War II.

Finally, the authors suggestion that tightening was in response to the tax cuts appears to be only partially true at best. Reductions in the balance sheet, for example, were announced in June 2017, before the tax cuts were even considered, and started in October before any legislation had been produced. The policy continued as planned after passage.

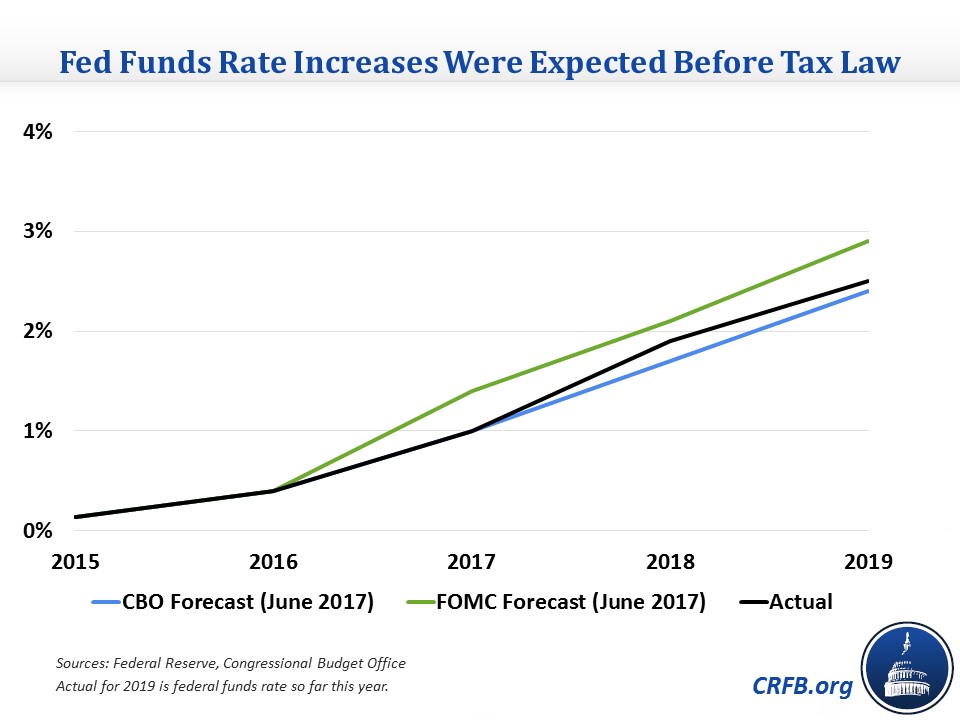

Interest rate increases were also mostly a continuation of Fed policy pre-tax cut. The Federal Reserve increased rates by 0.25 percentage points in 2015, 0.25 points in 2016, and 0.75 points in 2017 before the tax cuts were enacted, and the Fed followed them with an additional 1 point hike over the course of 2018. Estimates suggest this increase was modestly higher than it would have been in the absence of the tax cuts, but not dramatically so. Indeed, the federal funds rate today is lower than the Fed's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) projected and only a few tenths of a percentage point higher than CBO had anticipated it would be when they made their projections prior to the tax cuts.

While Fed interest rates might not have risen as fast absent the tax cuts, it is clear that they did not tighten dramatically in light of the tax cuts.

Unfortunately, Brady and Lindsey also get several other claims wrong in their op-ed. For example, they claim that JCT "expected the benefits of the tax cuts to peter out after a year" and "argued that the tax law would stoke inflation." In fact, JCT and CBO both projected the tax cuts would continue to boost the economy by increasing amounts well into the 2020s and expected only a negligible effect on inflation.

In addition, the authors appear to conflate the possibility that the tax cuts may provide some permanent boost in the level of GDP, which CBO and JCT project will happen, with the idea that it would permanently increase the economy's growth rate, which no one projects will occur.

Finally, they argue that "there is no reason to expect the American growth machine to sputter out soon", even though growth already appears to be slowing. Just yesterday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated the economy grew at 2.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018, compared to 4.2 and 3.4 percent in the prior two quarters. Projections for the first quarter of 2019 are even lower.

Despite claims to the contrary, there is little evidence that the country will be able to sustain the 3 percent growth rate we experienced last year. And while it is possible Federal Reserve action will somewhat slow near-term growth, those actions are far from unprecedented and have only a little to do with the recent tax cuts.