The Still Unsolved Health Care Mystery

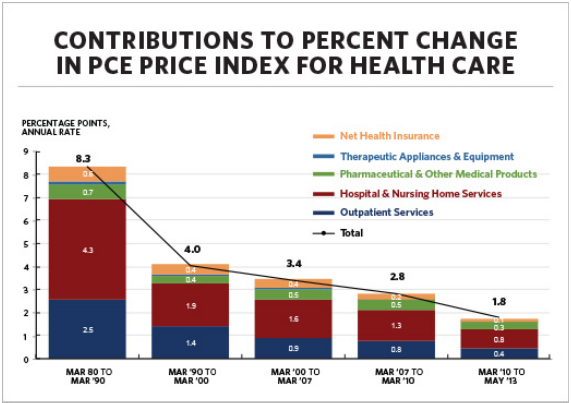

In yesterday's Washington Post, Robert Samuelson explores the unsolved "health spending mystery," whether the recent slowdown in health care spending growth is a permanent result of structural changes in health care, or just a temporary aberration from the recession. Samuelson's piece was prompted by a recent White House blog post from Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors Alan Krueger, who uses the chart below to show the significance of the deceleration of health care inflation, which he implicitly suggests could be related to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. But beyond the question of how much credit the ACA deserves is a more important question: how likely is it that the current trend will continue?

As we have discussed before, the growth of national health care spending has slowed in recent years, averaging 3.9 percent in each of the last three years compared to the historical mark of over 7 percent. This is a very welcomed development, especially if much of it is due to structural changes which are bending the health care cost curve rather than temporary economic factors or one time savings which reduce the level but not rate of health spending.

Source: White House

As we’ve explained before, the slowdown is almost definitely from a mixture of factors. Unusually low inflation means slower price growth everywhere. Deep economic recessions tend to reduce utilization and put downward pressure on prices. One time shifts in what or how we use or pay for medicine (including shifts caused by some upfront cuts in the Affordable Care Act) appear to be reducing the level of health spending. And some structural changes in the way we produce and consume health care are hopefully slowing future growth rates. The trillion dollar question is how much of the slowdown is explained by each factor, and the evidence on that question is mixed.

A notable report from the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Altarum Institute found that 77 percent of the slowdown could be explained by changes in the broader economy, suggesting that much of what we are seeing is just temporary. By contrast, Harvard Professors David Cutler and Nihkil Sahni argue that 55 percent of recent trends cannot be explained in their model, ascribing 37 percent to economic conditions and 7 percent to a decline in private coverage, which could indicate fundamental shifts are taking place. Without clear evidence to the contrary, it is hard to assume a dramatic slowdown.

We very much hope that Cutler and Sahni are right, but history should caution policymakers from becoming too optimistic. The 1990s also saw a slowdown in health care cost growth, which was initially attributed to the expansion of managed care and Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), along with legislated reductions in Medicare spending. Unfortunately, this trend was reversed in the early 2000s. It is too early to draw conclusions from recent events with any confidence.

Although the current slowdown buys some breathing room for the Medicare and Medicaid programs, it should not be used as an excuse to make worthwhile reforms which rationalize cost-sharing rules, improve the way we pay for care, reduce fraud and abuse, and pay providers based on value. Even if health spending were definitely under control, it would still be incumbent on policymakers to spend scarce taxpayer dollars as efficiently and effectively as possible. This is especially true given not only the likelihood that per person health spending will rise, but also the fact that the majority of the increase in federal health care spending over the next few decades is not due to health but to aging.

As the Baby Boom generation moves into and makes its way through retirement the number of Medicare beneficiaries will grow substantially and those collecting Medicaid long-term care benefits will grow as well. Meanwhile, the older population within those programs will mean higher per-person costs, as the elderly population is the most expensive and especially so toward the end of life.

Recent health care trends have been encouraging but it's important not to overreact and conclude that the long-term health care spending problem has been solved. There are many health care options that should be on the table, ones that can reduce costs while preserving our commitment to health care. It isn't wise to just wait it out to see if our most optimistic hopes are realized.