Rep. Larson Proposes Social Security Reform

Rep. John Larson (D-CT) earlier in the summer unveiled his plan to reform Social Security, a plan that has now been evaluated by the Social Security Administration's Office of the Chief Actuary (OACT). The reform would fully close Social Security's 75-year shortfall and about three-quarters of the 75th year deficit, meaning that it would ensure 75-year solvency but not sustainable solvency.

First, thank you. It is tremendous to see a Member of Congress addressing Social Security’s challenges with real fixes. As we have pointed out, the longer we delay, the harder those fixes will be.

The plan is certainly a useful contribution to the debate, recognizing not only the magnitude of the changes that will have to be made to close Social Security’s gap, but also that increasing scheduled benefits, as the plan does, will require significant revenue increases that go beyond just higher taxes on the wealthy.

- Raise the payroll tax rate by 2 percentage points to 14.4 percent, phased in over 20 years

- Apply the payroll tax to income above $400,000 unindexed (the current taxable maximum would catch up around the mid-2040s due to indexation) and credit benefits for that income through a special lower "AIME+" benefit factor

- Increase the income threshold for the taxation of Social Security benefits to $50,000/$100,000

- Increase the lowest PIA factor in the benefit formula from 90 to 93 percent

- Use the faster-growing CPI-E for cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs)

- Create minimum benefit of 125 percent of the poverty line for people who have worked 30 years or more

- Invest one-quarter of the trust fund in equities

- Re-allocate revenue to the DI trust fund to keep it solvent

| Larson Plan Effects on Social Security Shortfall | ||

| Policy | Change in 75-Year Shortfall | Change in 75th Year Deficit |

| Adopt CPI-E | -14% | -11% |

| Increase lowest PIA factor | -9% | -6% |

| Increase minimum benefit level to 125% of poverty | -8% | -7% |

| Increase thresholds for Social Security benefit taxes | -4% | -0% |

| Re-allocate revenue to DI trust fund | 0% | 0% |

| Subtotal, Benefit Increases/Tax Cuts | -35% | -24% |

| Increase payroll tax by 2% | 53% | 41% |

| Apply payroll tax to incomes above $400,000 | 67% | 49% |

| Diversify investment of trust fund assets | 14% | 0% |

| Subtotal, Pay-Fors | 135% | 90% |

| Total Effect | 102% | 74% |

Source: OACT

Note: Numbers may not add up due to rounding and interactions

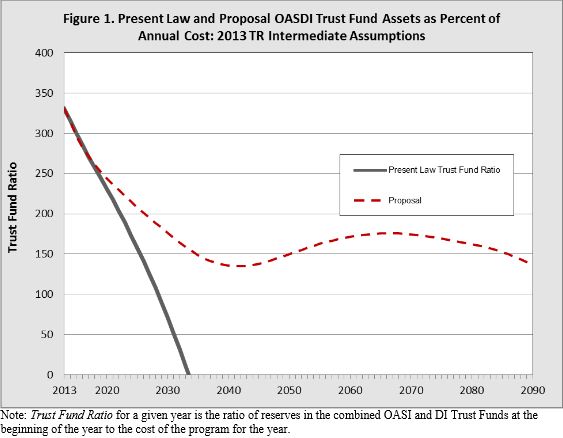

Overall, the plan would reduce the 75-year shortfall by 2.77 percent of taxable payroll, enough to close the 2.72 percent shortfall (OACT evaluated the plan based on last year's Trustees report). In the 75th year, the plan would reduce the 4.8 percent of payroll shortfall by 3.55 percentage points (about 75 percent), meaning that the plan does not reach sustainable solvency and the trust fund ratio (the ratio of assets to benefits) would be declining at the end of the projection period. Thus, more would need to be done in later years to keep the trust fund solvent. The plan would not entirely eliminate cash-flow deficits in any year (though it would come close in 2050), but it would keep them small enough to maintain the trust fund over the next 75 years.

Source: OACT

The plan would certainly make a large improvement to the program's finances. Closing all of Social Security's 75-year gap and three quarters of its 75th year gap is no easy feat, and this plan recognizes the need for some tough medicine -- in this case, opting to raise taxes on all workers -- to do so. At the same time, we do have some concerns.

The plan includes tax increases equal to more than 1.6 percent of GDP -- with about one quarter of that revenue paying for new spending. That's five times larger than the taxes raised in the fiscal cliff deal -- which was incredibly contentious. Given the need to finance an underfunded highway system, various new priorities supported by both parties, and rapidly growing health care costs, it's not clear that putting all that revenue into Social Security makes sense. Certainly, we are not opposed to raising revenue to help fund Social Security, as bipartisan plans have done including Simpson-Bowles and Liebman-MacGuineas-Samwick, but if that revenue is so large that it leaves no revenue on the table for other needs, it becomes a concern.

Second, at a time when Social Security costs are already growing significantly, this plan would increase those costs by spending more on everyone. New costs would be more manageable if it instead pursued targeted benefit enhancements. Instead, the plan would increase spending not just for low earners, but also for the middle class, the upper-middle class and even millionaires and billionaires (although the increases are better targeted than in Senator Harkin's reform bill).

One of these benefit increases is from adopting the CPI-E (which attempts to measure inflation experienced by the elderly) for COLAs, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics itself and CBO have found to have a number of methodological flaws. The CPI-E suffers from substitution bias, small sample size bias, problems accurately measuring the growth in health prices, problems appropriately measuring housing costs, and problems measuring senior discounts, among other flaws. Indeed, CBO has argued that "it is unclear, however, whether the cost of living actually grows at a faster rate for the elderly than for younger people."

There is also the matter of the proposal's plan to close 15 percent of the 75-year imbalance by investing the trust fund in equities instead of government bonds. While stocks do indeed grow faster than bonds, on average, they also come with higher risk and volatility, which is not captured in the estimate above. Moreover, every dollar invested in equities means a dollar increase in debt held by the public. This is not to say diversification of the trust fund should not be on the table, but it is no free lunch.

Social Security will be insolvent by 2033, and reform grows more difficult as time passes. Congress should strive to reform Social Security sooner rather than later. By introducing a proposal that makes the program solvent, Larson has made a positive contribution to the reform conversation. However, policymakers should be mindful of the limited resources available when looking to align Social Security benefits and revenue. While it may well make sense to fix Social Security separately from the rest of the budget, we still need to think about the budget overall when considering what government priorities (including closing the fiscal gap) should lay claim to new revenues.