Once Again, the Chained CPI Is Not Regressive

After being included in both the most recent White House and Republican offers, the "chained CPI" has been front and center as a potential piece of any compromise to avoid the fiscal cliff. A number of critics of the policy (see here, here, and here) have voiced concern about the chained CPI, attacking the option as a regressive Social Security cut and tax increases. To address these concerns, we explored the distributional impact of chained CPI in the most recent update of our report, "Measuring Up: The Case for Chained CPI."

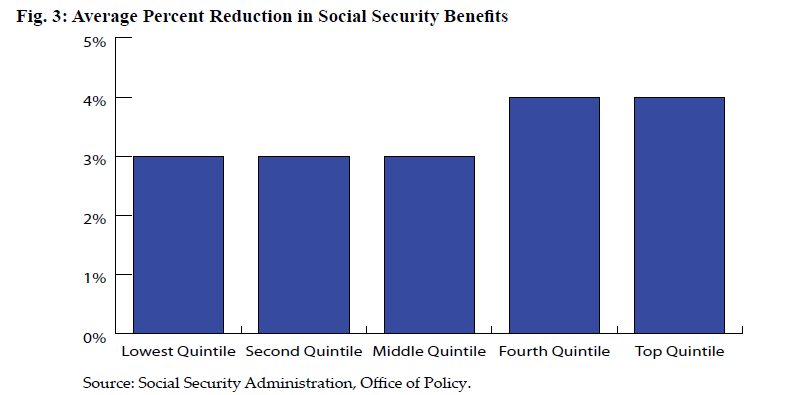

On Social Security, cost-of-living adjustments offer the same percentage increase for all their beneficiaries, therefore a COLA that grows more slowly would be distributional neutral in theory. Differences due to other factors, including a greater cut for those who receive benefits for a longer time, actually make the change slightly progressive. This table from the Social Security Administration show that the benefit cut would be greater for those in the top two quintiles.

On the tax side, switching to chained CPI would affect tax brackets, the standard deduction, personal exemptions, and other features of the tax code. Other than those who have a negative tax burden, most everyone would be affected - with TPC finding each quintile on average receiving a 0.2 percent reduction in their after tax income over the next decade. On average, the chained CPI's effects are roughly distributionally neutral -- though those at the very very very bottom and very very top would bear a smaller relative burden.

Standing alone, switching to chained CPI is more or less distributionally neutral. But policymakers may want to achieve an outcome more progressive than the current system and may want to protect certain vulnerable populations. With regards to Social Security, the best way to do that is to enact a comprehensive package which makes the system solvent in the context of modifying the benefit formula and offering other features such as a minimum benefit. Short of that, however, policymakers could protect the old-old by combining chained CPI with a benefit bump-up for the very old. As an example, the Simpson-Bowles plan included a flat dollar increase equal to 5 percent of the average benefit available phased in beginning 20 years after eligibility.

Whereas by itself benefit reductions are equal by income group in the same cohort, the change is quite progressive when combined with such a policy. The graph shows the benefit change at age 86, since that is when the bump-up would be fully phased-in under a Simpson-Bowles type policy.

Source: Social Security Administration, CRFB Calculations

Likewise, switching to the chained CPI on the tax side has clearly not prevented major bipartisan plans from being substantially more progressive than the current code.

It makes no sense to continue overstate inflation if the most vulnerable can be protected with additional policies.

Click here to read our updated Measuring Up report.