OCO Gimmick Makes an Unwanted (and Unnecessary) Comeback

A few weeks ago, we talked about the Senate veterans bill proposed by Senator Bernie Sanders, which would increase spending on veterans and pay for it by extending some expiring savings provisions and by using the war gimmick. That bill is now set to move forward in the Senate this week.

Only one thing has changed since we first wrote about it: the military cost-of-living adjustment reduction repeal has already taken place for current service members as enacted in the debt ceiling bill. This repeal eliminates the savings from the COLA reduction for at least 20 years, so repealing it entirely no longer has a cost in the ten-year CBO score (although it would have longer-term costs). As a result the bill now reduces mandatory spending -- the spending that would occur without further action by Congress -- by slightly more than $1 billion rather than increasing mandatory spending by approximately $5 billion.

The bill does authorize an additional $21.7 billion for discretionary programs, but spending on those programs are subject to appropriations. Under budget rules, the costs of discretionary programs are scored to appropriations bills that actually provide spending authority and are subject to the discretionary caps in law. The discretionary authorizations in the bill do not by themselves affect actual spending or the deficit; only the provisions affecting mandatory spending would do so. Thus, enactment of the bill would reduce the deficit by more than $1 billion.

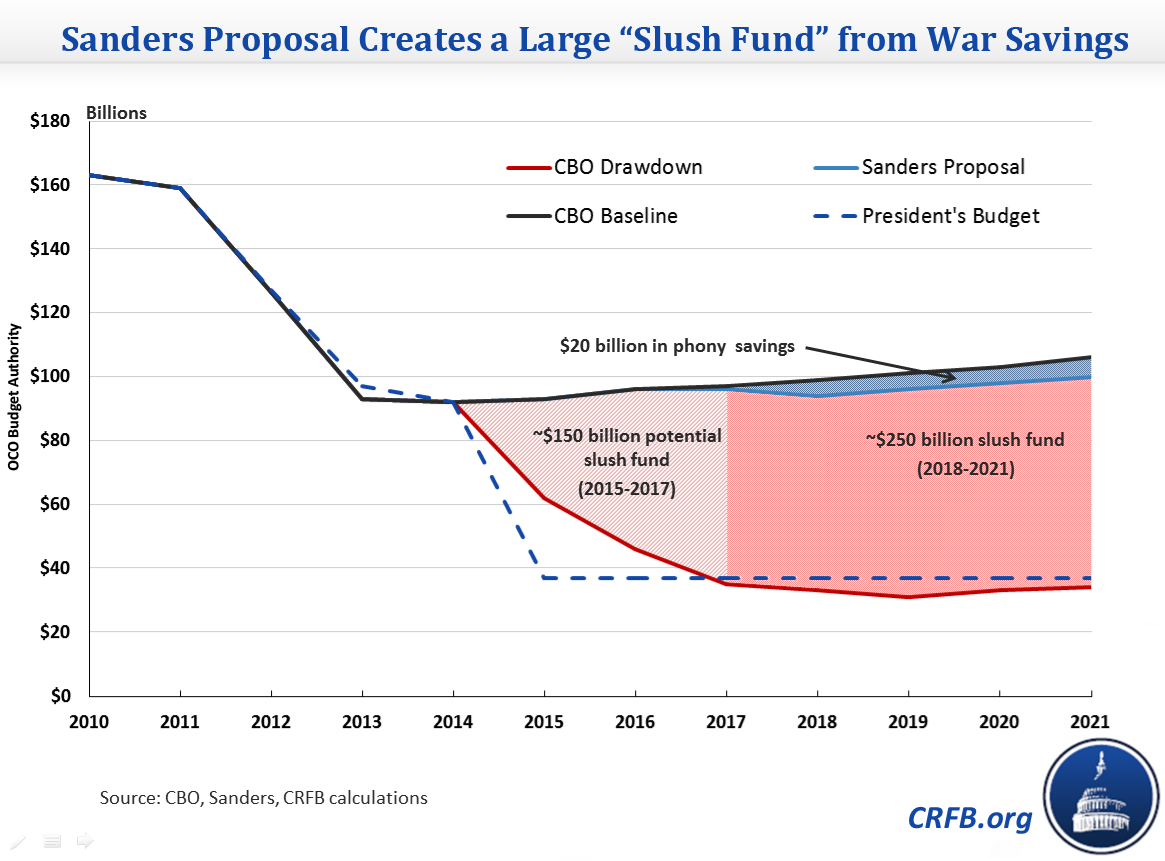

The problematic part of the bill is that it still maintains the war gimmick by putting in caps in 2018-2021 that are $5 billion lower per year than in CBO's baseline for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). While the gimmick no longer necessary to offset the military COLA reduction, it still leaves open the possibility -- and makes more likely -- the future use of war savings as an offset. Since the war spending caps the bill would put in place are barely a drawdown from CBO's baseline, it would not restrain war spending but would formalize OCO as a slush fund.

Congress could provide funding for base defense spending that could not fit within the existing defense caps through the OCO category and justify it by saying the spending was still below the OCO caps. Moreover, establishing caps well above anticipated future war spending would create a mechanism that would allow Congress to claim hundreds of billions of future "savings" to offset mandatory spending increases by continually lowering the caps to more realistic levels that Congress would likely abide by anyways. Essentially, this would legitimize the use of war spending caps as a slush fund to circumvent budget rules without placing any meaningful restraint on war spending.

We've pointed out many times that using war spending as an offset is a gimmick since the caps are simply meant to reflect plans already in place. To quote CBO (emphasis added):

The proposed limits on appropriations are $20 billion below the $409 billion projected for such operations over the 2018-2021 period in CBO's baseline. That $409 billion figure, however, is just a projection; such funding has not yet been provided, and there are no funds in the Treasury set aside for that purpose. As a result, reductions relative to the baseline might simply reflect policy decisions that have already been made and that would be realized even without such funding constraints. Moreover, if future policymakers believed that national security required appropriations above the capped amounts, they would almost certainly provide emergency appropriations that would not, under current law, be counted against the caps.

Creating this slush fund is unnecessary for the underlying bill itself and opens the door for fiscally irresponsible legislation that use the war gimmick as offsets. To be sure, repealing the reduction in military retirement COLAs for future enrollees will have a long term cost that will place pressure on the defense budget and should be replaced by other long term savings, ideally from other reforms of defense entitlements. Likewise, increasing discretionary authorizations places increased pressure on appropriations, and identifying savings in other discretionary authorizations can reduce that pressure. But setting a cap on OCO spending does not serve either of these purposes, particularly one set at a such a high level that will have no practical effect.

If lawmakers are to put caps on war spending, they should set them at levels to reflect the drawdown underway to lock should in those savings already expected to occur and prevent the OCO category from being used to circumvent restraints on other parts of the budget without taking credit for achieving new savings. Otherwise, they are simply playing games with it.