Maya MacGuineas: A Social Security ‘Fix’ That Falls Short

Maya MacGuineas, President of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, wrote a commentary that appeared in the Wall Street Journal Washington Wire. It is reposted here.

It’s election season, which means the time to demagogue Social Security is again upon us. Those trying to avoid difficult trade-offs in Social Security reform often say that all we have to do to is “tweak” the system by lifting the $117,000 payroll tax cap so all wages are subject to the tax.

Taxing all income above $117,000 at 12.4% would raise more than $100 billion a year–far from a tweak. And never mind that the government has many other priorities that might be a better use for new funds, such as covering growing health-care costs, making overdue investments in infrastructure and R&D, or controlling the national debt.

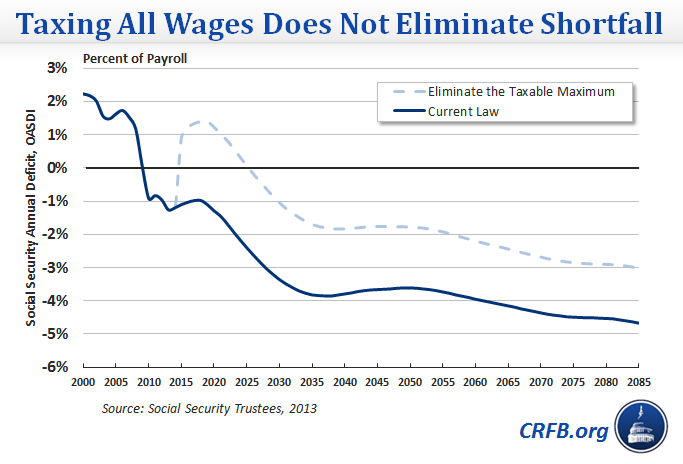

Even if we eliminate the cap–and there is a good case for at least raising it–that wouldn’t make Social Security even close to solvent.

According to the Social Security Administration (SSA), eliminating the cap would close about 70% of the system’s 75-year imbalance. According to Congressional Budget Office accounting, it would close only 45% of the gap.

The SSA found that eliminating the cap on payroll taxes would close only one-third of the shortfall in the 75th year. This is important because it shows whether the reform would help make the system structurally sound or whether it would generate largely short-term savings. Eliminating the cap would generate only 10 years of surpluses before the benefits Social Security pays out again begin to exceed the revenue it takes in.

Part of the reason the change would not be more effective is that while Social Security might begin taking in more revenue, it would also be on the hook for paying out larger benefits down the road. One smart way to address this would be a form of means-testing, where there would be no additional benefits associated with the additional contributions from those making more than $117,000. This would generate more revenue for Social Security while better targeting its benefits. But this change is often opposed by progressives who fear it would break the traditional link between contributions and benefits. Those critics need to decide whether providing new benefits to people who don’t need them is really worth giving away a significant portion of the gains that would be achieved by lifting the cap.

But even if Social Security didn’t pay out additional benefits should it take in increased revenue, eliminating the taxable maximum would still close only about 85% of the shortfall, according to Social Security Administration calculations (and much less according to the CBO), and just half of the deficit in the 75th year. So under any scenario, lifting the cap on taxing wages would need to be accompanied by other changes to bring the program’s spending and revenue in line.

So the next time you hear candidates say they would solve the Social Security shortfall by eliminating the cap on wages, ask what else they would do. Lifting the cap isn’t enough, and we’re running out of time to make smart, gradual changes to avoid insolvency, protect those who depend on Social Security most, and give workers sufficient time to plan and adjust.

"My Views" are works published by members of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, but they do not necessarily reflect the views of all members of the committee.

Related Posts:

- CRFB's MacGuineas Dispels Five Social Security Myths

- Report: Analysis of the 2014 Social Security Trustees' Report

- Setting the Record Straight On Social Security