The Longer We Wait, The Tougher the Choices Become

In our recent paper, "Our Long-Term Debt Problems are Very Far From Solved," we showed that while the debt problem may be long-term, solutions need to start today. Similar to our analysis of the cost of delaying reform to Social Security, the cost of closing our fiscal shortfall rises over time as we lose the ability to take advantage of compounding interest savings and the ability to spread the adjustment over more years.

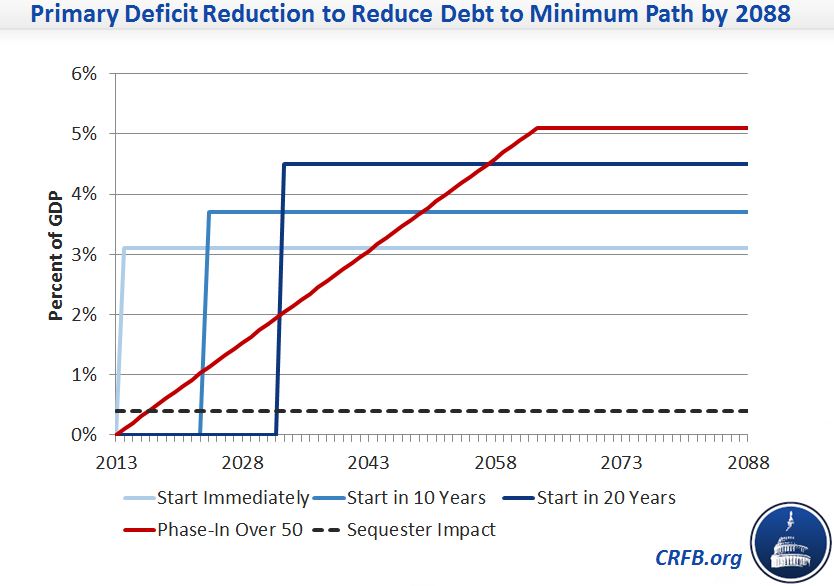

In our analysis, we modeled the minimum changes necessary to bring debt down to historical levels of GDP by 2088, as in our "Minimum Path," to put the debt on a clear downward path as a share of the economy.

In order to put debt on a clear downward path through 2088, policymakers would need to enact immediate and permanent spending cuts or tax increases (excluding interest) equal to 3.1 percent of GDP. However, if lawmakers were to wait 10 years before acting, an adjustment of 3.7 percent would be needed; if they waited 20, an adjustment of 4.5 percent would be required. If savings were slowly phased in over 50 years, which is far more likely than a massive immediate adjustment, spending cuts and tax increases (excluding interest) would need to reach 5 percent of GDP. Keeping the sequester in place only reduces the necessary deficit reduction by 0.4 percent - still leaving large adjustments to be made down the road if lawmakers delay additional deficit reduction policies.

As the above graph makes clear, the longer we wait the deeper any cuts or tax increases must be. This is doubly true given that fewer cohorts of people will be able to share in the burden of these adjustments (meaning more cuts per person).

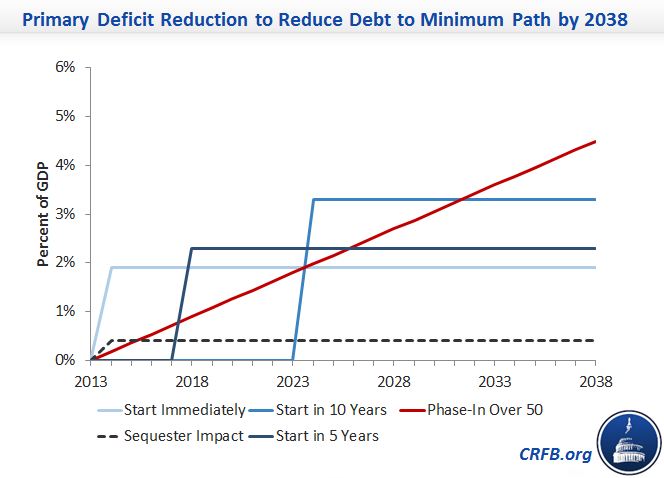

Our paper showed estimates over a 75-year timeframe. But what about a shorter timeframe? Over a 25-year time horizon, our Minimum Path suggests that debt levels should fall from 73 percent of GDP today to just below 60 percent – dropping by about 0.6 percent of GDP per year. To close this gap, an immediate 1.9 percent of GDP adjustment would be necessary. Yet this rises dramatically to 3.3 percent if lawmakers wait ten years before starting and to a virtually unachievable 8.3 percent of GDP if they wait for 20 years.

Note: The "Starting in 20 Years" has been excluded from the chart for comparability, but would require an adjustment of 8.3 percent

There is a cost to waiting regardless of which budget window lawmakers decide is appropriate; and it is important lawmakers keep that cost in mind when contemplating further delay in action.

It is preferable to phase in changes and adjustments gradually rather than begin them immediately, but even that phase in is not free. And while the benefits of phasing in a policy may outweigh the costs, it is hard to say the same about the benefits of delaying legislative action. The longer we wait to begin making changes, the larger and more abrupt any tax increases and spending cuts will have to be, the fewer people will be able to share in the burden of those cuts, and the less warning individuals and businesses will have to prepare.