Kamala Harris's LIFT the Middle Class Act

Democratic presidential candidate Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) has called for giving a $3,000 per person ($6,000 per couple) refundable tax credit for most middle- and working-class Americans through her LIFT (Livable Incomes for Families Today) the Middle Class Act.

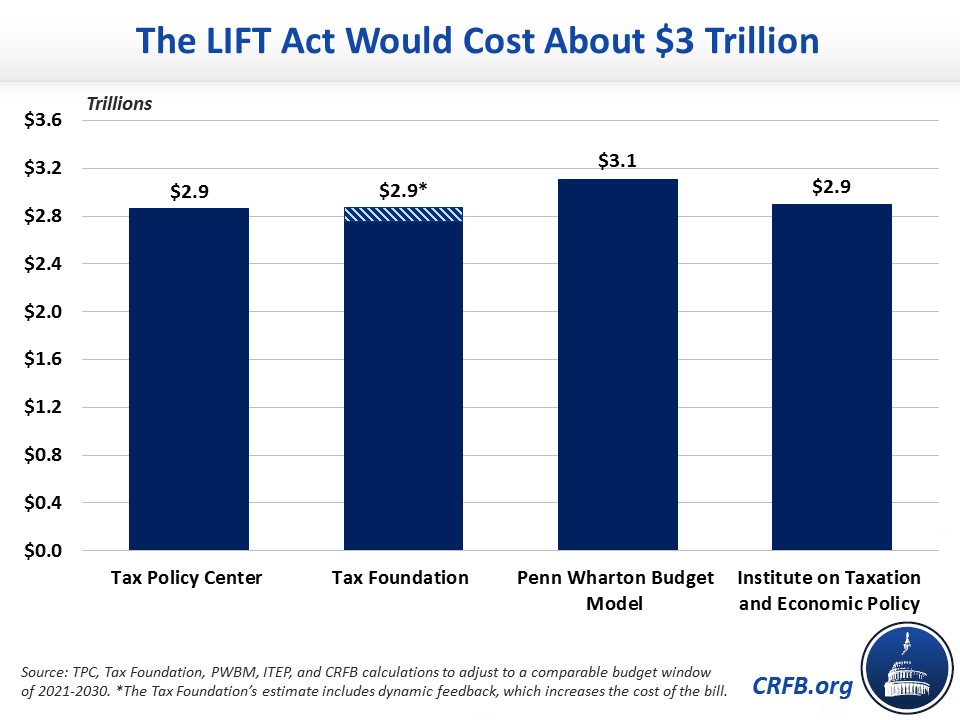

The LIFT Act would provide significant tax relief and benefits and, according to outside estimates, would cost roughly $3 trillion over the next decade, the equivalent of about 6.5 percent of current law revenue and 1.1 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In order to offset the cost of the LIFT Act, Senator Harris has proposed to enact a fee on large financial institutions and repeal all provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) except those providing relief to taxpayers earning less than $100,000 per year. The amount the LIFT Act would be offset depends on interpretation.

Repealing the TCJA tax provisions while retaining only tax relief for those making less than $100,000 would raise enough revenue to cover about one-fifth of the act’s cost through 2030. A much more aggressive interpretation that assumes provisions in the TCJA are retained (including revenue-increasing provisions) except for tax relief for higher earners and corporations would raise enough to cover roughly 85 percent of the cost.

The following is a policy explainer generated as part of US Budget Watch 2020, a project covering the 2020 presidential election. In the coming weeks and months, we will continue to publish analyses of candidate proposals that are having the greatest impact on the debate over our nation’s future. You can read more of our policy explainers and factchecks here. US Budget Watch 2020 is designed to inform the public and is not intended to express a view for or against any candidate or any specific policy proposal. Candidates’ proposals should be evaluated on a broad array of policy perspectives, including but certainly not limited to their approaches on deficits and debt.

What is the LIFT the Middle Class Act?

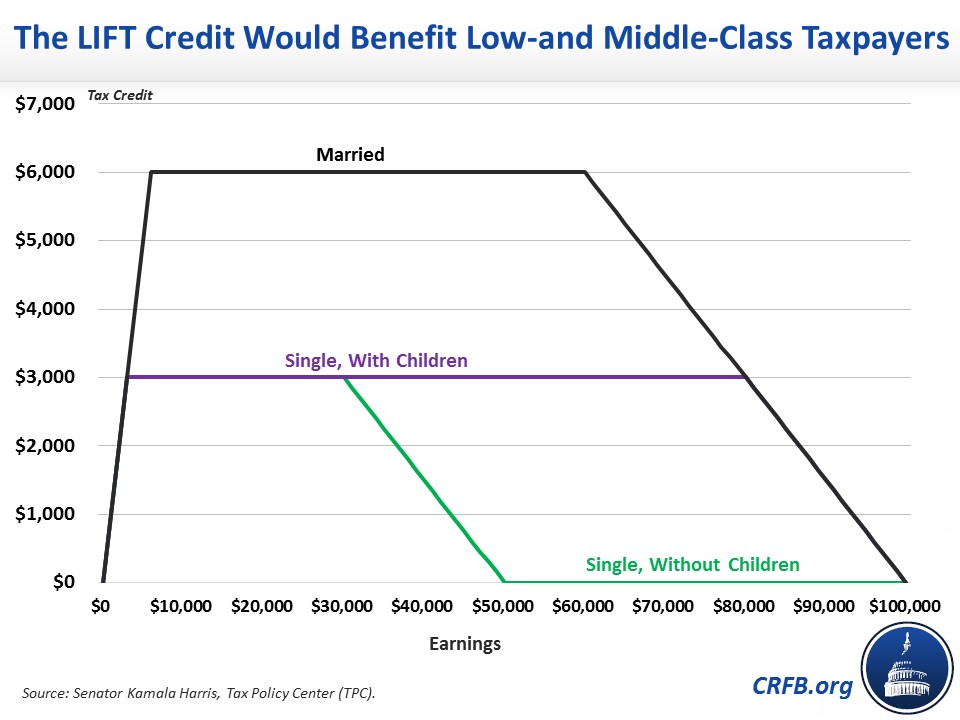

The LIFT the Middle Class Act would provide a refundable tax credit up to $3,000 per year for low- and middle-income adult workers and $6,000 per married couple. The LIFT credit would be structured much like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), though the size of the credit wouldn't be contingent on the number of children a taxpayer has.

For a childless individual, the LIFT credit would be refundable up to $3,000 for anyone earning more than $3,000 but less than $30,000 per year. If an individual earns less than $3,000 a year, the LIFT credit would match income dollar for dollar, meaning someone who earns $2,000 per year would receive a $2,000 credit. For those earning more than $30,000 per year, the credit would phase out by 15 cents for every dollar earned above $30,000, disappearing fully above $50,000 of income. The credit and phase-out thresholds would double to $6,000, $60,000, and $100,000 for a married couple. A single parent would receive a $3,000 credit, but the phase-out threshold would be between $80,000 and $100,000, rather than $30,000 and $50,000.

The LIFT credit would be offered on top of other tax credits – including the EITC and Child Tax Credit (CTC) – and would be available to households with labor earnings, Pell Grant recipients, and dependent taxpayers over the age of 18 who file tax returns. Claimants could collect the credit on a monthly or annual basis, and the credit would be indexed to inflation.

Overall, the LIFT credit would increase the progressivity of the federal tax code and increase after-tax income for most households earning less than $100,000 per year. The Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates that nearly half of all taxable units would receive a tax cut averaging $3,200 in 2019. The average tax cut among all taxpayers would be closer to $1,500, with almost no tax break for those in the top income quintile, an average credit of less than $900 for taxpayers in the second highest income quintile, and an average tax cut of about $2,000 for everyone else. Estimates from the Tax Foundation and Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) came to similar conclusions.

Because the LIFT credit is relatively flat outside of the phase-in and phase-out thresholds, it is very progressive relative to income, meaning lower-income taxpayers would benefit relatively more than higher-income taxpayers. TPC estimates a 12.6 percent boost in after-tax income for the bottom income quintile, a 6.3 percent boost for the second quintile, a 3 percent boost for the third quintile, and a 1 percent increase for the fourth income quintile. These estimates do not account for offsets that may be used to pay for the LIFT credit.

The LIFT credit would not be available to children or low-income Americans who do not work or attend school. It would also be unavailable to those with more than $3,850 in investment income.

How Much Would the LIFT Act Cost?

A number of estimates show the LIFT Act would cost roughly $3 trillion over a decade and may slow economic growth modestly, resulting in a small additional revenue loss.

On a conventional basis, TPC estimates the LIFT Act would cost $2.8 trillion through 2028, while the Tax Foundation estimates $2.7 trillion and PWBM estimates $3.1 trillion in costs. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) projects the LIFT credit would cost $270 billion in 2020 alone. We estimate that under these projections, the cost from 2021 through 2030, the ten-year budget window when Senator Harris would become President, would range from $2.8 trillion to $3.1 trillion.

The above estimates do not include feedback from the economic impact of the proposal. As PWBM, TPC, and the Tax Foundation explain, the LIFT Act is likely to slow economic growth modestly. The LIFT credit’s phase-out would increase a taxpayer's marginal tax rate by roughly 15 cents for each additional dollar earned (according to PWBM, a single worker earning $40,000 would face a marginal tax rate of 27.2 percent instead of 13.1 percent), which would reduce the incentive to work. The LIFT Act would also produce an income effect where individuals would work less knowing that they have additional income from the credit. Partially offsetting these effects, the LIFT Act would encourage work among taxpayers in the phase-in threshold, boost the number of Americans searching for work, and provide economic stimulus when first enacted.

Estimates from the Tax Foundation find the LIFT Act would reduce GDP by 0.7 percent over the long run. On a dynamic basis, this would lead to an additional $83 billion in ten-year revenue loss ($16 billion in 2028 alone), bringing the total projected cost of the LIFT Act to $2.8 trillion through 2028 (or about $3.0 trillion over 2021-2030). This estimate does not include the potential impact of borrowing or raising taxes in order to finance the LIFT credit. Based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates, either repealing the TCJA or increasing debt would further reduce economic output.

Would the LIFT Act Be Paid For, and How?

Senator Harris proposes a framework for offsetting the cost of the LIFT Act, though it is unlikely the pay-fors will cover the total cost, particularly over the long run. Specifically, Senator Harris calls for repealing all provisions of the TCJA except those that provide tax relief to taxpayers with less than $100,000 in annual income and imposing a fee on financial institutions with assets over $50 billion.

Because Senator Harris has not specified which provisions of the TCJA she would repeal, it is impossible to estimate the revenue implications of the LIFT Act with total certainty. However, it would require an aggressive interpretation of TCJA repeal in order to raise close to $3 trillion in revenue.

Since the costliest provisions of the TCJA are set to expire after 2025, repealing all the law’s tax provisions beginning in 2021 would only raise about $1.1 trillion (excluding changes to the individual mandate). With about three-quarters of the revenue loss going to taxpayers earning over $100,000, this implies roughly $800 billion in revenue if it were possible to repeal all tax cuts for those earning above $100,000 and none for those earning below $100,000. The legislation also calls for taxing large financial institutions. Although the legislation would allow Treasury to set the rate, similar policies estimated or proposed by CBO, President Obama’s budget, and the Tax Reform Act of 2014 would all have raised around $100 billion. Under this scenario, only about one-fourth of the total cost of the LIFT Act would be offset.

The TCJA is a complex piece of legislation with provisions that both reduce and increase taxes, many of which cut across income groups. It would be extremely difficult to literally repeal all tax cuts for taxpayers earning more than $100,000 and none going to those earning less than $100,000 since some provisions affect both groups (like the reductions in tax rates).

Instead, lawmakers would need to go provision by provision and decide whether to repeal, retain, or modify each. Different interpretations of Senator Harris’s offset framework would result in significantly different amounts of revenue. A very aggressive interpretation would be necessary to come close to covering the full cost of the LIFT Act.

On the lower end, one interpretation would involve repealing all tax provisions of the TCJA – including revenue reductions and increases – except for provisions that offer relief to taxpayers with annual income under $100,000. This would mean retaining the lower tax rates below $100,000 of income, the doubling of the standard deduction and CTC in place of personal exemptions, and the special pass-through deduction on income below $100,000; it would mean repealing all corporate tax provisions, the rate cuts and other tax relief for higher earners, various deduction limits, and a change in how provisions in the tax code are indexed each year. By our estimates, this interpretation of TCJA repeal would raise about $500 billion through 2030 (mostly by 2026) – or $600 billion when adding the tax on financial institutions. This would cover just about one-fifth of the full cost of the LIFT Act.

Repealing All Tax Provisions of the TCJA Except Tax Reductions for Taxpayers With Incomes Under $100,000

| Policy | Revenue Impact (2021-2030) |

|---|---|

| Raise individual income tax rates above $100,000 to pre-TCJA levels | $400 billion |

| Restore the Individual AMT, Pease Limitation, and estate tax to pre-TCJA levels | $200 billion |

| Repeal individual revenue-raising provisions in the TCJA | -$600 billion |

| Repeal pass-through provisions for those making over $100,000 | $100 billion |

| Repeal business tax reform, both tax cuts and increases | $400 billion |

| Tax large financial institutions | $100 billion |

| Total | $600 billion |

| Percent of LIFT Act covered (assuming $3 trillion cost) | ~20% |

Source: Very rough CRFB calculations based upon Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation, and Open Source Policy Center’s Tax Brain.

Raising enough revenue to cover most of the costs of the LIFT Act would require a much more aggressive interpretation – one which assumes all tax provisions of the TCJA are retained, including revenue-increasing provisions, except those offering (gross) tax relief for corporations and households making above $100,000 per year. Under this interpretation, the corporate income tax rate would be restored to 35 percent (from 21 percent now), but no corporate tax breaks that were repealed or reduced in the TCJA would be restored. At the same time, the higher individual income tax rates and lower alternative minimum tax (AMT) thresholds would be restored on individuals and couples making over $100,000 per year, while the $10,000 cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and other revenue raisers would remain for all taxpayers, including those earning less than $100,000. We estimate this scenario would raise $2.5 trillion in additional revenue and offset about 85 percent of the total cost of the LIFT Act.

Repealing Only Tax Provisions of the TCJA That Offer Reductions for Corporations and Taxpayers With Incomes Above $100,000

| Policy | Revenue Impact (2021-2030) |

|---|---|

| Raise individual income tax rates above $100,000 to pre-TCJA levels | $400 billion |

| Restore the Individual AMT, Pease Limitation, and estate tax to pre-TCJA levels | $200 billion |

| Phase out the expanded CTC starting at $100,000 of income | $200 billion |

| Repeal pass-through deduction for those making above $100,000 and retain the limit on high-income households using business losses to reduce other income | $200 billion |

| Raise corporate tax rate to 35 percent and keep corporate base broadening | $1,400 billion |

| Tax large financial institutions | $100 billion |

| Total | $2,500 billion |

| Percent of LIFT Act covered (assuming $3 trillion cost) | ~85% |

Source: Very rough CRFB calculations based upon Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation, and Open Source Policy Center’s Tax Brain.

While this aggressive scenario would offset most of the cost of the LIFT Act in the first decade, it would cover far less over the long term since most of the individual provisions of the TCJA expire after 2025 under current law. It is possible that Senator Harris proposes to pay for the LIFT Act relative to an alternative baseline that assumes provisions in the TCJA don’t expire in 2025 as scheduled, but this assumption is counter to current law and normal budget conventions.

It is also important to note that the combination of new borrowing and any of the repeal options above would likely slow economic growth modestly by reducing work, savings, and investment. The result would be a somewhat higher net cost than implied by the figures above.

Where Can I Learn More?

- Legislative Text, as Introduced in the 116th Congress – S.4 LIFT (Livable Incomes for Families Today) the Middle Class Act

- Senator Harris’s Senate Website – Harris Proposes Bold Relief for Families Amid Rising Costs of Living

- Senator Harris’s 2020 Campaign Website – Issues: Economic Justice

- Penn Wharton Budget Model – Analyzing the Budgetary and Incentive Effects of Senator Kamala Harris’s Proposed LIFT Act

- Tax Foundation – Analysis of Sen. Kamala Harris’s LIFT the Middle Class Act

- Tax Policy Center – Kamala Harris’s Tax Credit Would Cut Taxes Significantly for Low-Income and Moderate-Income Households But Could Add Trillions to the Debt

- Tax Policy Center – Senator Harris Seeks to Raise Incomes Using A New Tax Credit

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy – LIFT the Middle Class Act

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy – Shaking Up TCJA: How a Proposed New Credit Could Shift Federal Tax Cuts from the Wealthy and Corporations to Working People

- Vox – Kamala Harris’s New Basic Income-Style Bill is So Frustratingly Close to Being Great

- The Atlantic – Kamala Harris’s Trump-Size Tax Plan

****

With the 2020 campaign now in full gear, the presidential candidates are putting forward many ambitious proposals aimed at solving very real problems and concerns. The voting public deserves to know how much these proposals will cost and what it would mean for the debt we will be leaving to our children and grandchildren.

This policy explainer is part of our US Budget Watch series covering the 2020 presidential election. In the coming weeks and months, we will continue to publish analyses of candidate proposals that are having the greatest impact on the debate over our nation’s future. You can read more of our policy explainers and factchecks here.