Increasing Infrastructure Investment Must Be Paid For

In a recent interview with The New York Times, President Trump said that he wants to invest $1 trillion in infrastructure because "we are borrowing very inexpensively" right now; this implies an interest in deficit-financing new infrastructure investments. There is a strong case for increased infrastructure investment and a case for taking advantage of today’s low interest rates to frontload investment. However, with today’s post-war era record-high and rising debt levels, there is no good case for adding hundreds of billions of dollars to the national credit card without a plan to pay for it.

Below, we explain why despite low interest rates, any national infrastructure plan should be fully paid for over a reasonable period of time.

The National Debt is Too Damn High

Were the national debt under control and the budget roughly in balance, there might be a case for prioritizing pro-growth investment over further debt reduction. However, the national debt today is too high and growing too rapidly to justify further borrowing.

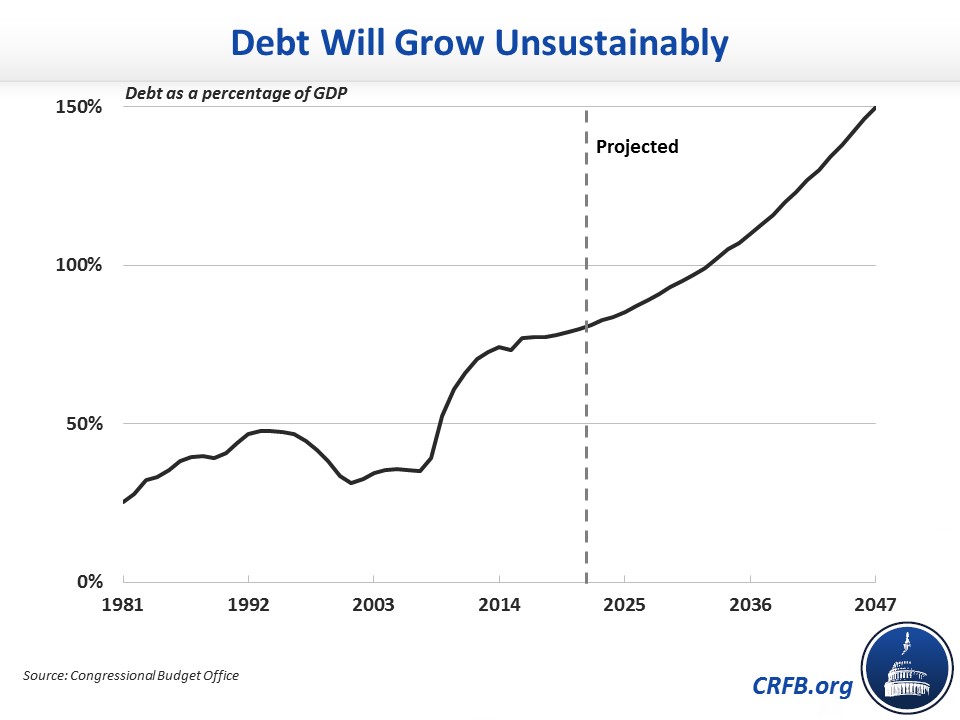

At 77 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), debt held by the public today is a larger share of the economy than any time in history outside of World War II, and it is projected to double over the next three decades. This trajectory is harmful to economic growth and ultimately unsustainable, and adding to it further by debt-financing new spending (or tax cuts) would be a huge mistake.

Even continuing to borrow as under current law would shrink the economy by three percent after three decades relative to a base case where debt does not rise. It would also reduce available fiscal space and increase the likelihood of a fiscal crisis.

Low Interest Rates May Be Temporary, But Debt is Forever

Some argue for investing in more infrastructure in order to take advantage of today’s historically low interest rates.

While there are certainly benefits to financing high-return investments with low-interest loans, most of those advantages disappear without a strategy to ultimately pay the loan back.

Today’s low interest rates are unlikely to last forever. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that interest rates on ten-year Treasuries will rise from 2.2 percent today to 3.6 percent in 2027 and 4.7 percent by 2047, while rates on three-month bonds will rise from 0.8 percent today to 2.8 percent by 2027. As a result, interest is already the fastest-growing part of the budget.

Without a plan to pay back borrowing, low-interest rate bonds will eventually be redeemed and replaced (“rolled over”) with higher interest rate bonds. Indeed, this situation could be exacerbated by a large debt-financed infrastructure package, since both the higher debt and higher public investment will have the effect of pushing up interest rates further.

One way to solve for this “rollover cost” would be to only finance projects that fully pay for themselves over time and therefore have little net cost by the time low-interest bonds are replaced with high-interest bonds. However, in order to pay for itself, a project would either need to create $4 to $6 of economic activity for every $1 spent* or else establish a lucrative new revenue stream (tolls or tickets, for example) for the government. It is doubtful that many investments meet those criteria, especially investments meant to serve a public purpose. CBO has estimated a typical debt-financed public investment will not only fail to pay for itself but will actually cost the federal government 10 percent more than its initial costs over a decade due to the economic cost of higher debt.

A way to protect against rollover cost may be to issue longer-term bonds. The Treasury Department is already increasing the average length of the bond it issues, and there may be a case to do so more aggressively. But, importantly, issuing bonds with a longer maturity period will increase interest costs today (for example, the interest rate on 30-year bonds is about 2.9 percent compared to 2.3 percent for ten-year bonds and 0.8 percent for three-month bonds). Moreover, without a plan to ultimately pay for increased investment, even the longer-term bonds will eventually be rolled over.

Debt-Financed Infrastructure Could Shrink the Economy

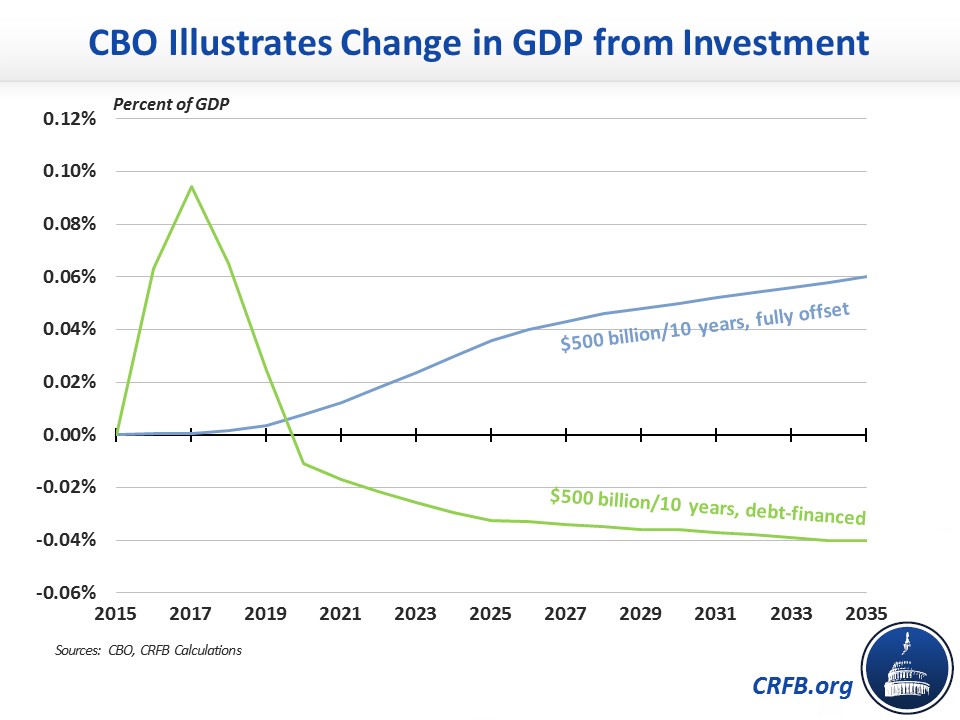

In June 2016, CBO issued a report analyzing the impact of increased federal investment on the budget and economy. In particular, they compared the impact of higher public investment that was paid-for to debt-financed investment (they assumed half of investment would go toward physical capital like infrastructure, while the rest would go towards education, training, and research and development).

CBO found that a $500 billion package of paid-for investment would increase the size of the economy by 0.04 percent after a decade and 0.06 percent after two decades. On the other hand, they estimated debt-financed investment would decrease the size of the economy by 0.03 percent after a decade and 0.04 percent after two decades.

In other words, while public investment would help to grow the economy, CBO estimates the harm from higher debt would do even more to stunt economic growth.

Low Interest Rates May Offer an Opportunity to Buy Now, Pay Later

With debt at record-high levels, temporary low interest rates don’t change the need for policymakers to fully pay for all new initiatives. However, these low rates may strengthen the case for borrowing more in the very near term and paying that borrowing back over time before much debt has been rolled over into higher interest rate bonds.

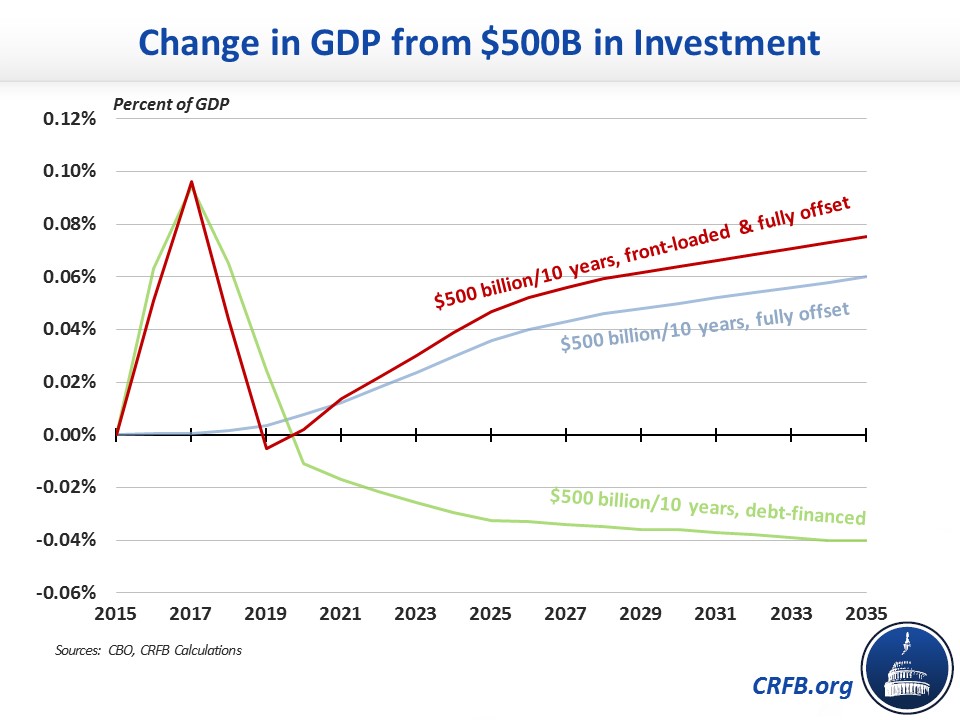

Last year, we modified CBO projections to estimate the effect of frontloading new investments. Rather than assuming the government appropriated (and offset) $50 billion of investments per year for ten years, as CBO did in its base case, we assumed the government appropriated $180 billion of investments over two years and then $40 billion per year after that. In other words, we assumed the same $500 billion as CBO but with much more of the spending occurring in the early years. Meanwhile, we assumed the offsets phased in gradually over five years so that new investments would only add to the debt in the early years, but these deficits would be completely paid off after a decade.

Whereas CBO estimated $500 billion of debt-financed investment would shrink the economy by 0.04 percent after 20 years and $500 billion of paid-for investment would increase it by 0.06 percent, we estimate that $500 billion of frontloaded but paid-for investment would grow the economy by 0.05 percent after ten years and almost 0.08 percent after 20 years. (As a side note, even that is still equal to only about 0.004 percent of increased growth per year, less than one five hundredth of what it will take to get to 4 percent growth.)

By taking advantage of today’s low interest rates but offsetting the costs of new investment before much debt is rolled over, it does appear policymakers can achieve of a win-win.

Importantly, though, that win-win still requires making choices of what spending to cut or what taxes to increase in order to make room for new investment. With trillion dollar deficits returning by 2023 – and the vast majority of those deficits financing interest and consumption spending – policymakers need to start prioritizing. Just as tax cuts must be offset and won’t pay for themselves, the same applies for infrastructure spending. There is no magic in budgeting – only choices.

*An average tax rate of 25 percent implies a policy would need to produce $4 of economic activity for every $1 spent to pay for itself on a present-value basis. However, higher immediate-term debt and growth effects are both likely to increase interest rates and therefore interest payments on current debt; this implies an even higher necessary return is needed.