How Does Our Corporate Code Compare to Other Countries?

In our newest paper, "Reforming the Corporate Tax Code," CRFB makes the case for why the U.S. needs to reform the corporate tax code, discussing its high marginal rates, its incredible complexity, and its relative inefficiency. Using data from the OECD highlighted in our paper, we can see how the U.S. stacks up with other countries.

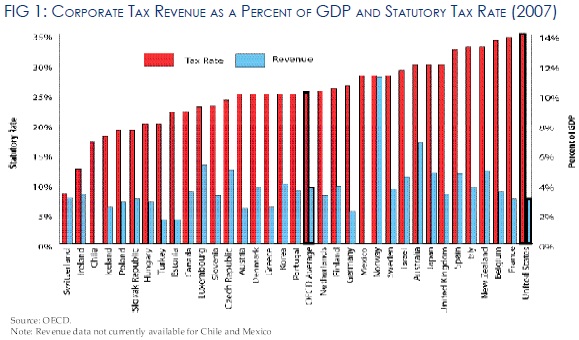

In 2010, when data were last available for revenue, the U.S. had the highest statutory corporate tax rate of any central government of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) at 35 percent. At the same time, the corporate tax raised 2.7 percent of GDP, compared to the OECD unweighted average of 2.9 percent of GDP. In 2007, the last pre-crisis year, the U.S. raised 3.0 percent of GDP, while the OECD average was 3.8 percent. According to CBO, the corporate tax will raise only 2.2 percent over the next decade. This relatively low revenue is partially due to the fact that the effective corporate tax rate is well below the 35 percent rate, but it also due to the fact that the U.S. is less restrictive on which businesses -- especially businesses with higher receipts -- can be classified as pass-through entities, which are not subject to the corporate tax.

Another area where the U.S. sticks out is in how they tax the foreign income of domestic multinational companies. The U.S. currently has a deferral system, in which companies are not taxed on foreign income by the U.S. until it is repatriated to the U.S. (although certain passive income is taxed as it is earned under Subpart F). This system simultaneously encourages countries to move resources abroad and discourages them from bringing resources back.

By contrast, many of our trading partners, particularly developed countries, have territorial systems, where income is only taxed by the country where it is earned. These countries also have put in regimes to tax passive income and prevent artificial profit-shifting to tax havens. Some tax reform plans would shift to a territorial system, while others would shift to a worldwide system, where U.S. multinationals are taxed by the U.S. on their worldwide income as it is earned.

It is clear that many other developed countries' corporate tax systems outperform the U.S.'s in terms of efficiency. There is definitely room for improvement. As our paper said:

By combining all the potential benefits of corporate tax reform done right, a fiscally responsible remake of the tax code can improve the strength of the economy, fueling job creation and wage growth in the future. However, corporate tax reform would be most successful if enacted as part of a broader effort to reform the entire tax code and put the national on a sustainable, downward path over the medium and long term.

Click here to read our corporate tax reform paper and click here to design your own corporate tax plan.