Deficit-Financed Tax Cuts May be Counterproductive

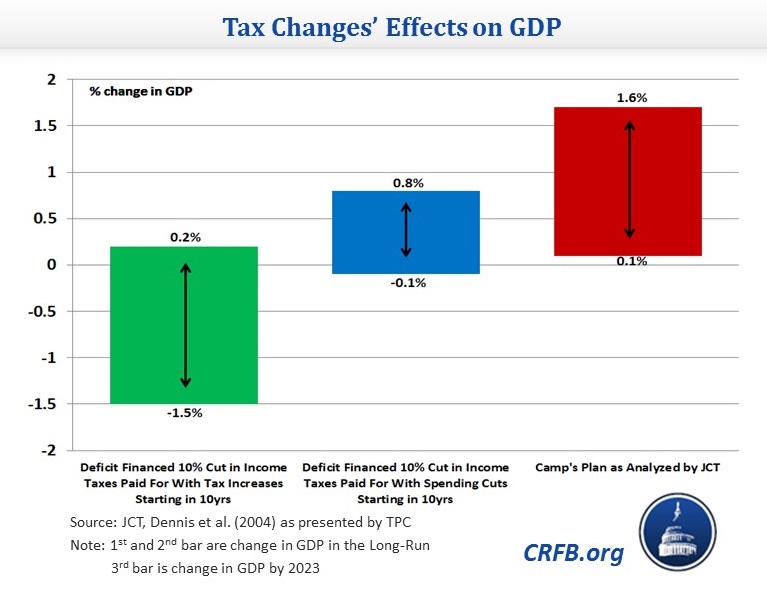

A new paper suggests that tax cuts that add to the deficit provide little boost to economic growth and may actually hinder it. Last week, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) put out a paper entitled “Effects of Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth,” summarizing the academic literature. According to the authors, Bill Gale from Brookings and Andrew Samwick from Dartmouth, the net economic impact of a deficit-financed income tax cut is either small or negative, with the negative effects of additional debt likely overwhelming the economic benefit of lower rates, particularly over the long term.

Tax cuts have the potential to grow the economy, but their benefit depends on how they are structured and financed. For tax changes to promote growth, changes should encourage work and investment through lower rates, efficiently encourage new economic activity (rather than providing a windfall for previous investments), reduce economic distortions, and create minimal (if any) increases in the budget deficit.

The key question is, how do you pay for tax cuts? If tax cuts are deficit-financed, the negative economic effects of debt will crowd out investment, which can outweigh any positive growth impact from the tax cut. CBO has found that an “Alternative Fiscal Scenario” representing roughly a $2 trillion increase in deficits over ten years would lead to a 7.5 percent smaller economy in 25 years, while a deficit reduction plan of $4 trillion would increase the size of the economy by 2 percent. Increased revenue has been a key part of many bipartisan plans for deficit reduction, including Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin.

Importantly, however, the lack of growth from deficit-financed tax cuts is distinct from the effects of either tax reform, which pairs rate reductions with base broadening, or tax cuts that are financed through simultaneous spending reductions to reduce government consumption. Using base broadening to pay for lower rates avoids crowding out other investment, but would likely temper the economic gains because some base broadening can push up effective marginal tax rates on taxpayers who were taking advantage of the closed loopholes.

The authors explain that tax cuts funded simultaneously either through base broadening or spending cuts likely have a positive effect on the supply-side of the economy—though the effects may be smaller than many policymakers think because many of the most positive results in economic literature are simulations of rather drastic and likely politically infeasible tax reforms.

The even greater advantage of deficit-neutral tax reform comes from reducing present inefficiencies and distortions in the tax code. Less growth comes from lowering marginal tax rates, because the benefits are partially counteracted by reductions in tax expenditures.

Luckily, there is a recent example of the economic benefits of tax reform. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) this spring put out an economic analysis of the Tax Reform Act of 2014 released by House Ways & Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI). JCT estimated an increase in GDP of between 0.1 percent and 1.6 percent by 2023 if the Camp Plan is implemented.

| 2014-2023 Economic Effect of the Tax Reform Act | |||

| Low Estimate | High Estimate | Average of All Estimates | |

| % Change in Real GDP | +0.1% | +1.6% | +0.65% |

| $ Change in Real GDP | +$0.2 trillion | +$3.4 trillion | +$1.4 trillion |

| % Change in Labor Supply | +0.3% | +1.5% | +0.6% |

| % Change in Private Employment | +0.4% | +1.5% | +0.8% |

| Change in Employment | +0.5 million | +1.8 million | +1 million |

| % Change in Business Capital Stock | 0% | -0.6% | -0.25% |

| Change in Revenues (Dynamic Score) | +$50 billion | +$700 billion | +$300 billion |

Note: Estimates for changes in economic output and labor force participation are rounded to the nearest $100 billion and 100,000 people, respectively.

See our blog post here for more information.

The TPC paper discusses individual income tax changes, so it does not discuss corporate tax reform, which is included in JCT’s analysis of the Camp plan. Because many businesses pay tax under the individual income tax code, many experts prefer tax reform which covers both individuals and corporations simultaneously, so that policymakers can address business taxation in a comprehensive way.

The paper also points to research that dispels the myth that higher taxes will necessarily slow the economy. Research such as a 2012 Congressional Research Service study by Thomas Hungerford indicates a lack of correlation between higher tax rates and lower growth. Additionally, the paper points to a 2012 study from the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities that reminds readers that economic and job growth were higher after the 1993 tax increase than the 2001 tax cut.

TPC's paper illustrates that tax cuts are a poor way to boost the economy if they increase deficits. Furthermore, CBO confirms that deficit reduction plans that raise revenue could help growth, not harm it.

For more tax-related analyses and materials, check out our Tax Reform Resource Page, or try reforming the corporate tax yourself with our Corporate Tax Calculator.