Checking the Facts on the Steve Forbes-Maya MacGuineas Tax Discussion

On Mornings With Maria, publisher and former presidential candidate Steve Forbes made several claims about tax cuts and economic growth during a segment with CRFB president Maya MacGuineas (watch here). Below we explore those claims and include a number of relevant facts.

Claim #1: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the economy will grow by 2.6 percent for the next ten years, which Republicans have accepted

As Forbes later clarified, CBO actually projects Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of 1.9 percent for most of the decade. This figure is substantially slower than the 3.2 percent historical average for growth since 1950 because of the aging and retirement of the population. The historical average includes several periods of strong labor force growth, which will not be repeated without large changes in labor or immigration policy – dramatically decreasing likely growth. This is why pro-growth policies are so important to adopt (and is also why we should pay for tax reform rather than adding to the debt).

As we wrote in How Fast Can America Grow?:

The 4.3 percent growth of the 1960s coincided with the large baby-boom population entering the workforce; the 3.5 percent growth of the 1990s coincided with them reaching their prime earning and productivity years. Now the baby-boomers are joining the ranks of the retired population, and the result is a significant economic slowdown.

CBO is in the middle of private forecasters, who assume growth rates of between 1.6 percent and 2.1 percent.

The 2.6 percent growth that Forbes refers to is the target of the Congressional budget resolution, which allows a tax reform bill to add up to $1.5 trillion in deficits on the premise that the economy will grow by 2.6 percent – almost one-third faster than current projections. However, no credible model finds growth effects that back up these numbers.

Claim #2: We should easily be able to do 3.5 percent or 4 percent growth

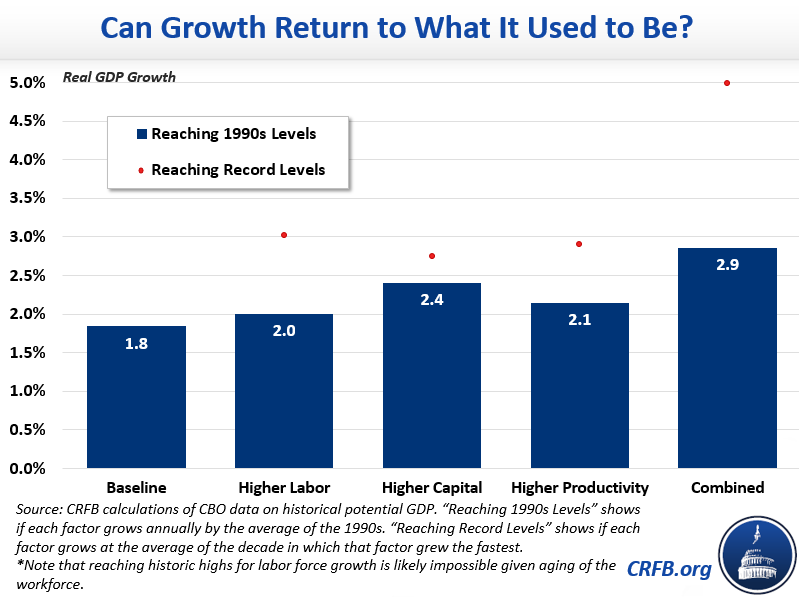

Easy? If only. Simply asserting a return to 3.5 percent growth is not enough to make it so. Growth estimates are based on the size of the labor force, the amount of capital available for investment, and the total productivity of the economy. But with an aging population, getting back to the historic average will take more than just tax reform.

To grow the economy by 3 percent annually, productivity growth, capital growth, and prime-age labor force participation would all need to return to the levels of the booming 1990s – an unlikely scenario given recent trends.

To reach 4 percent growth, productivity, capital investment, and labor force growth would each have to approach record levels. Hitting 4 percent growth would require tripling productivity growth, quadrupling capital investment, or reaching a totally unprecedented level of labor force growth – hardly easy and certainly not likely.

Claim #3: Every time we cut taxes across the board, like we did with Kennedy and Reagan, revenues went up not down, contrary to what CBO said… Reduce taxes and you’ll see revenues grow, as they always have in the past

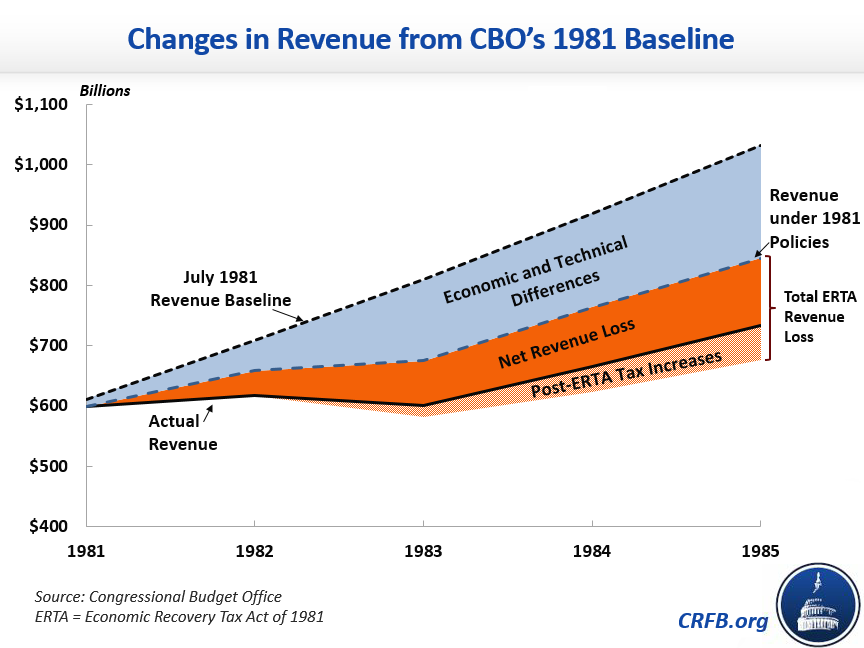

CBO was not around for the 1964 tax cuts, but contrary to Forbes's claim, the agency never predicted the 1981 tax cuts would cause nominal revenue levels to be lower than they were in 1981. Even without accounting for the subsequent tax increases, CBO estimated nominal revenues would still have increased from $599 billion in 1981 to about $677 billion in 1985 after the tax cut.

After the fact in 1985 and 1986, both CBO and President Reagan's own Office of Management and Budget actually said was that tax revenues were much lower than what they would have been without the tax cut. Both estimated the tax cuts lowered revenues in 1985 by about $170 billion compared to what they would have been otherwise, partially offset by subsequent tax increases enacted in response to the massive revenue loss.

The same is true of the tax cuts passed in 2001, 2003, and any other year. Tax cuts decrease revenue, they don't increase it.

Claim #4: Personal income tax receipts went up 50% from 1983 to 1989 after the Reagan tax cuts were fully phased in

Income tax revenues did increase by about 50 percent from 1983 to 1989 if measured in nominal dollars, but this has nothing to do with tax cuts growing the economy. Short of a major economic downturn or the years right after a major tax cut, revenues almost always increase in nominal terms each year because of inflation, population growth, and bracket creep. The real question is how much revenue did the government collect compared to what it would have been if we hadn't cut taxes.

It is much better to look at changes in revenue as a share of potential GDP, which helps control for factors like inflation, population growth, and recessions. Cyclically-adjusted revenue fell from 19.3 percent of potential GDP before the 1981 tax cuts to a low of 16.9 percent in 1986 before rising to 17.8 percent in 1989 – still well below the pre-tax cut levels.

And even this does not account for the fact that policymakers reversed a large portion of the 1981 tax cuts in subsequent years, and the economy was coming out of a deep recession in 1983, so a rebound in tax collections was expected. Revenues grew despite the tax cuts, not because of them.

Claim #5: Politically, you can only cut spending and reform entitlements when you have a booming economy, as was the case in the late 1960s and in the 1980s and 1990s.

If anything, this is a good argument for cutting spending and reforming entitlements now. While annual GDP growth has been below its historical average due to the aging of the population, the economy is essentially at full employment; the gap between actual and potential output is basically closed and the unemployment rate is just 4.1 percent.

However, when entitlement reforms occur has more to do with political leadership than it does with how the economy is performing. The landmark 1983 Social Security reforms were signed in April 1983, when the unemployment rate was over 10 percent, and the 1990 budget deal – which included reductions in Medicare spending and other mandatory programs – was signed when the economy was in a recession.

We are running out of time to address entitlements, which are already putting immense pressure on the rest of the budget. The longer we wait, the harder the problem is to solve. There are always excuses to kick the can, but the time for entitlement reform is now.

Claim #6: Kennedy and Reagan never tied tax cuts to spending cuts

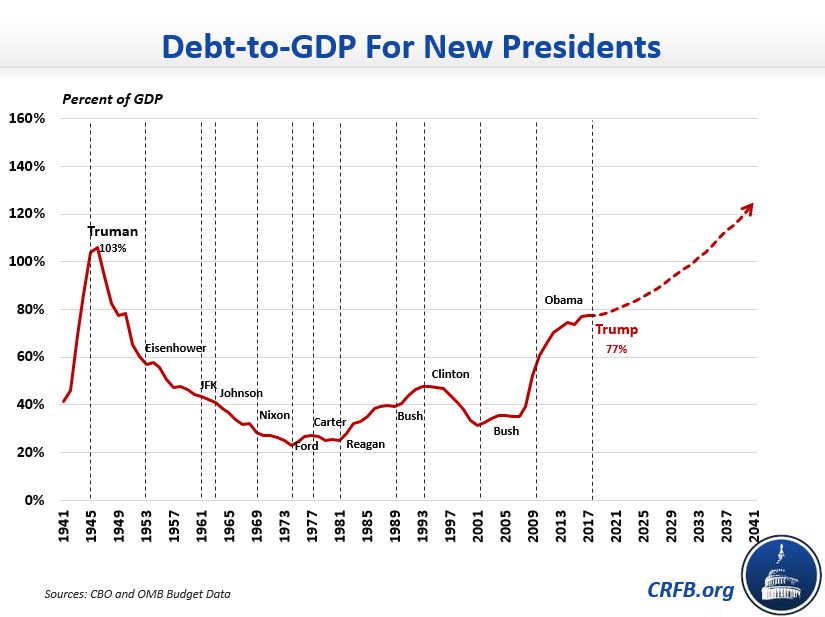

President Kennedy may not have tied tax cuts to spending cuts, but the country’s fiscal outlook in the 1960s was much different than it is now. In the fiscal year that Kennedy took office, the deficit was less than 1 percent of GDP and debt as a share of GDP was on a steady downward path. Now, the deficit is about 3.5 percent of GDP, and debt is projected to rise from its current post-World War II era high of 77 percent of GDP to an unprecedented 150 percent over the next 30 years. In addition, the top marginal tax rate before the 1964 tax cuts was 91 percent compared to 39.6 percent today – clearly a different situation.

President Reagan, meanwhile, pushed for significant cuts to both taxes and spending, even if he did deliver more on the former than the latter. The same day he signed the 1981 tax cuts into law, he also signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, which included significant spending cuts. The tax cuts enacted during Reagan’s first term were indeed much larger than the spending cuts, but that does not justify increasing the deficit now, especially given how much our fiscal situation has worsened since the 1980s.