Are We In For a (Tax) Cliff Hanger?

In honor of Tax Day on Tuesday, we will be doing blogs this week about the current shape of the tax code and what can be done to fix it. Our first blog will be about all the tax provisions that will expire at the end of the year, what has been labelled as "taxmageddon" (or the tax side of the fiscal cliff).

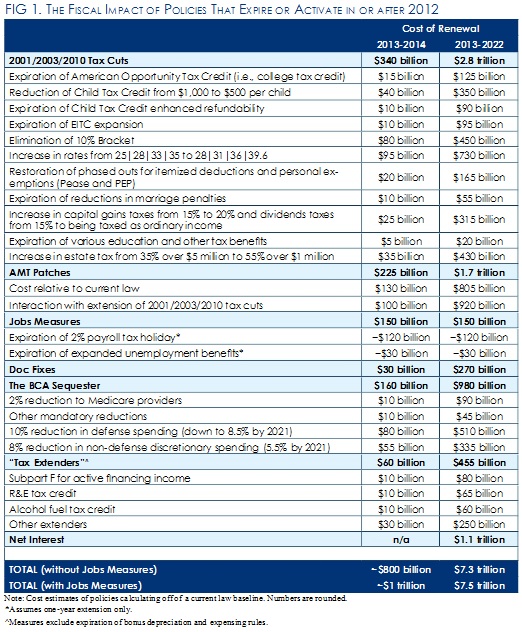

As our press release on Tax Day makes clear, the tax system has increasingly become temporary, and many temporary tax provisions are set to expire at the end of 2012, creating tremendous uncertainty for everyone. These expiring provisions affect taxpayers at all levels of income to varying degrees and affect a number of different targeted benefits that individuals and businesses receive; however, extending all of these would cost over $5 trillion over ten years. The provisions include:

- Tax rates: The 2001 tax cut lowered tax rates across the board, leading to tax brackets of 10, 15, 25, 28, 33, and 35 percent. If the 2010 tax cut expires, the 10 percent bracket will disappear and the other rates will be 15, 28, 31, 36, and 39.6 percent. Extending the brackets alone would cost about $1.3 trillion over ten years.

- Refundable tax credits: The 2001 tax cut increased the child tax credit from $500 to $1,000 per child and made it partially refundable, while increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit for married couples. The 2009 stimulus made the child tax credit more refundable, expanded the EITC for families with three or more children, and created the American Opportunity Tax Credit, a $2,500 refundable credit for college expenses that replaced the smaller non-refundable Hope credit. Continuing all of these credits at their current parameters would cost $665 billion over ten years.

- Capital gains and dividends: The 2003 tax cut lowered capital gains and dividends rates to 0 percent for people in the 10 and 15 percent brackets and to 15 percent for people above the 15 percent bracket. If these provisions expire, the rates would go back to 10 and 20 percent for capital gains and to ordinary income rates for dividends. Keeping these lower preferential rates would cost $315 billion.

- Estate tax: After the 2001 tax cut temporarily eliminated the estate tax in 2010, the 2010 tax cut reinstated the estate tax at a $5 million exemption (indexed for inflation beyond 2011; currently at $5.12 million) and a 35 percent top rate. If this provision expires, the estate tax will revert to the pre-2001 parameters of a $1 million exemption and a top rate of 55 percent. Extending the more generous estate tax parameters would cost $430 billion.

- Phaseouts: The 2001 tax cut also eliminated phaseouts of personal exemptions and itemized deductions for upper-income taxpayers (PEP and Pease, respectively), resulting in an effective rate cut for those who were previously hit by them. Permanently eliminating these phaseouts would cost $165 billion.

- Marriage penalties: The 2001 tax cut included a few provisions that were intended to reduce marriage penalties. These provisions extended the 15 percent bracket to higher incomes for married couples and increased their standard deduction. Extending these provisions would cost $55 billion.

- AMT patch: The Alternative Minimum Tax was originally created in 1969 to prevent high-income taxpayers from paying little or nothing in tax. However, the exemption was not indexed for inflation, so Congress has to act frequently to prevent the tax from hitting middle earners by increasing the exemption. The most recent patch expired at the end of 2011 but can be extended retroactively by the end of this year. The tax would only hit four million people if it is patched, but 30 million people if it isn't. Permanently patching the AMT would cost $800 billion on its own and $1.7 trillion if the other tax cuts are extended.

- Payroll tax holiday: The 2010 tax cut originally enacted the two percentage point payroll tax cut, which was scheduled to expire at the end of 2011. Congress acted late last year and again in February to extend it through this year. Although no official estimate currently exists, we estimate that extending the payroll tax cut for a year would cost about $120 billion.

- Other Tax extenders: Tax extenders are "temporary" and often narrowly-targeted tax provisions that are routinely extended (although that sounds like much of the tax code these days). The extenders are headlined by the popular R&E tax credit, which has been temporary for the past 30+ years. The extenders also include various energy incentives and other miscellaneous carveouts. All the extenders expired last year, but as with the AMT patch, they can be extended retroactively. Making them all permanent (excluding expensing provisions) would cost $455 billion.

As you can see from the descriptions above, there is something for everyone in these tax cuts. At the same time, there is a ton of money involved. How Congress handles all of these tax policies will be a major determinant in what our budget will look like going forward.

Note that the table and bullets above do not include taxes from the Affordable Care Act that will take effect in 2013, since those taxes are not temporary and are not generally discussed as a decision point to be made about the fiscal cliff. These taxes are highlighted by the 0.9 percent HI surtax on people making more than $250,000, and the 3.8 percent surtax that is applied to the investment income of those people.