Interest Payments in the Federal Budget

At a projected cost of over $300 billion this fiscal year, interest payments are a significant part of the federal budget. Net interest is currently the fifth-largest federal line item and costs more than federal spending on food and nutrition services, transportation, housing, education, or refundable tax credits.

This is true despite the record-low borrowing rates the federal government has faced through most of the COVID-19 pandemic. The growth in long-term Treasury yields this calendar year offers a reminder that low interest rates are not guaranteed to continue, as the pandemic-driven dip in long-term rates appears to be at least partially behind us. Regardless of whether interest rates maintain their upward trend, rising debt will cause interest payments to grow. In this paper we show that:

- Interest payments are a costly part of the federal budget. Even with exceptionally low interest rates, the United States is projected to spend over $300 billion on interest payments this fiscal year. That’s the equivalent of 9 percent of all federal revenue collections and roughly $2,400 per household.

- Interest rates declined due to COVID-19 but are now rising. The rate on ten-year Treasury bonds plummeted from 1.5 percent in February 2020 to just over 0.5 percent in early March 2020 and again in early August 2020. The rate has since rebounded to about 1.6 percent and could continue to rise. The Congressional Budget Office projects it will reach 3.4 percent by 2031 and 4.9 percent by 2051.

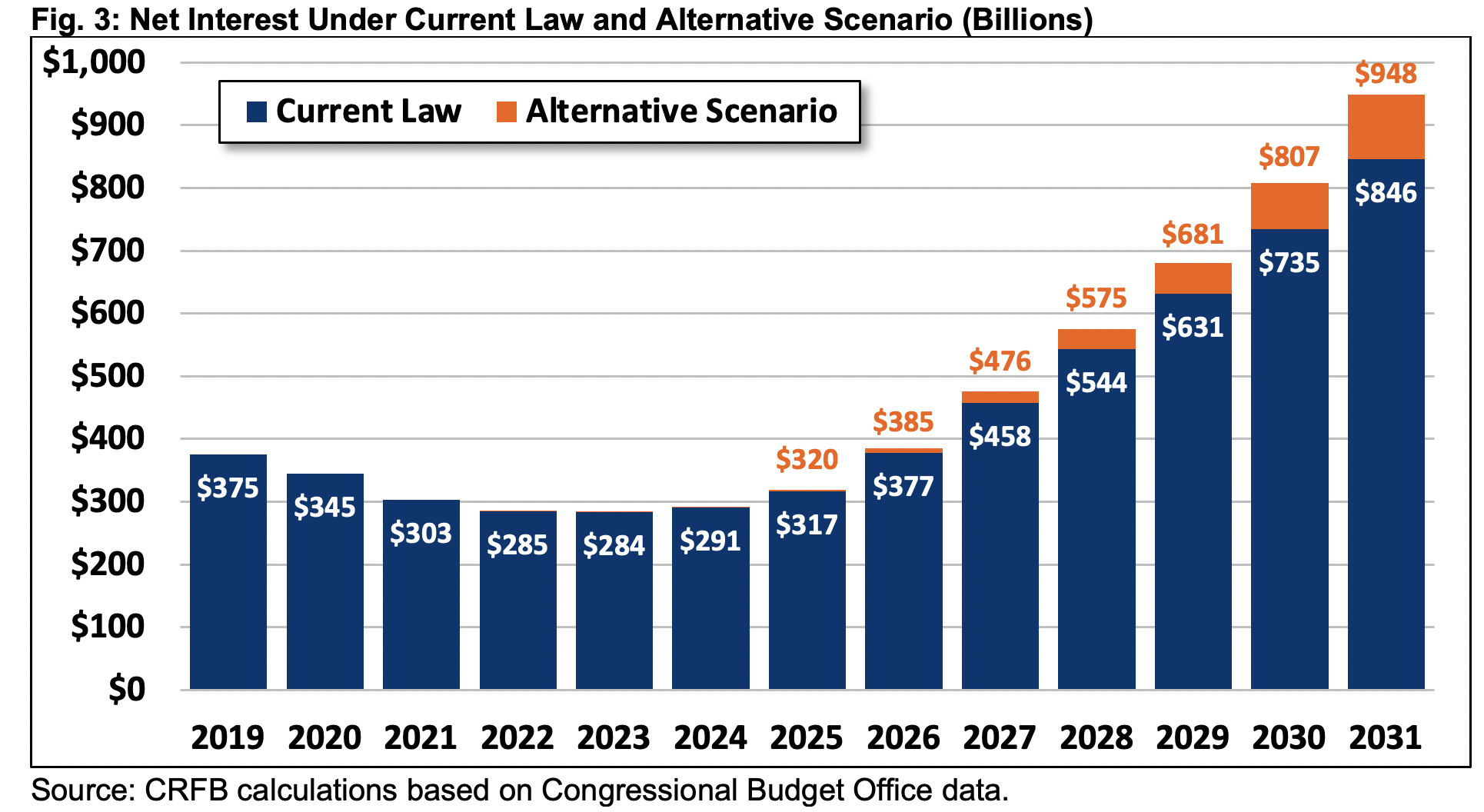

- Growing debt and rising interest rates will increase interest costs. As a result of recent rate declines, interest payments will decline from $375 billion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 to roughly $300 billion this year, despite nearly $7 trillion of new debt. Based on CBO projections, interest payments will fall further to $284 billion by FY 2023, then resume an upward trend. If rates rise as CBO projects (they are already higher than projected), interest costs will more than double, rising to $631 billion by FY 2029, $846 billion by 2031, and continuing to grow over the long term.

- Higher interest rates would further increase interest costs. We project interest spending to total $5.1 trillion over the 2021-2031 budget window. Yet, the interest rate on ten-year Treasury bonds is already more than half a percentage point higher than projected. If all rates end up being 50 basis points above projections, interest costs would increase by $1.7 trillion. Interest spending would increase by $3.6 trillion if rates were one percentage point higher than projected.

While no one can predict future interest rates with certainty, high levels of debt leave the country and the federal budget vulnerable to swings in interest rates. Already, interest payments consume a substantial share of the federal budget and crowd out other priorities. As debt and interest rates rise, the situation could worsen.

Interest Rates Are Rebounding

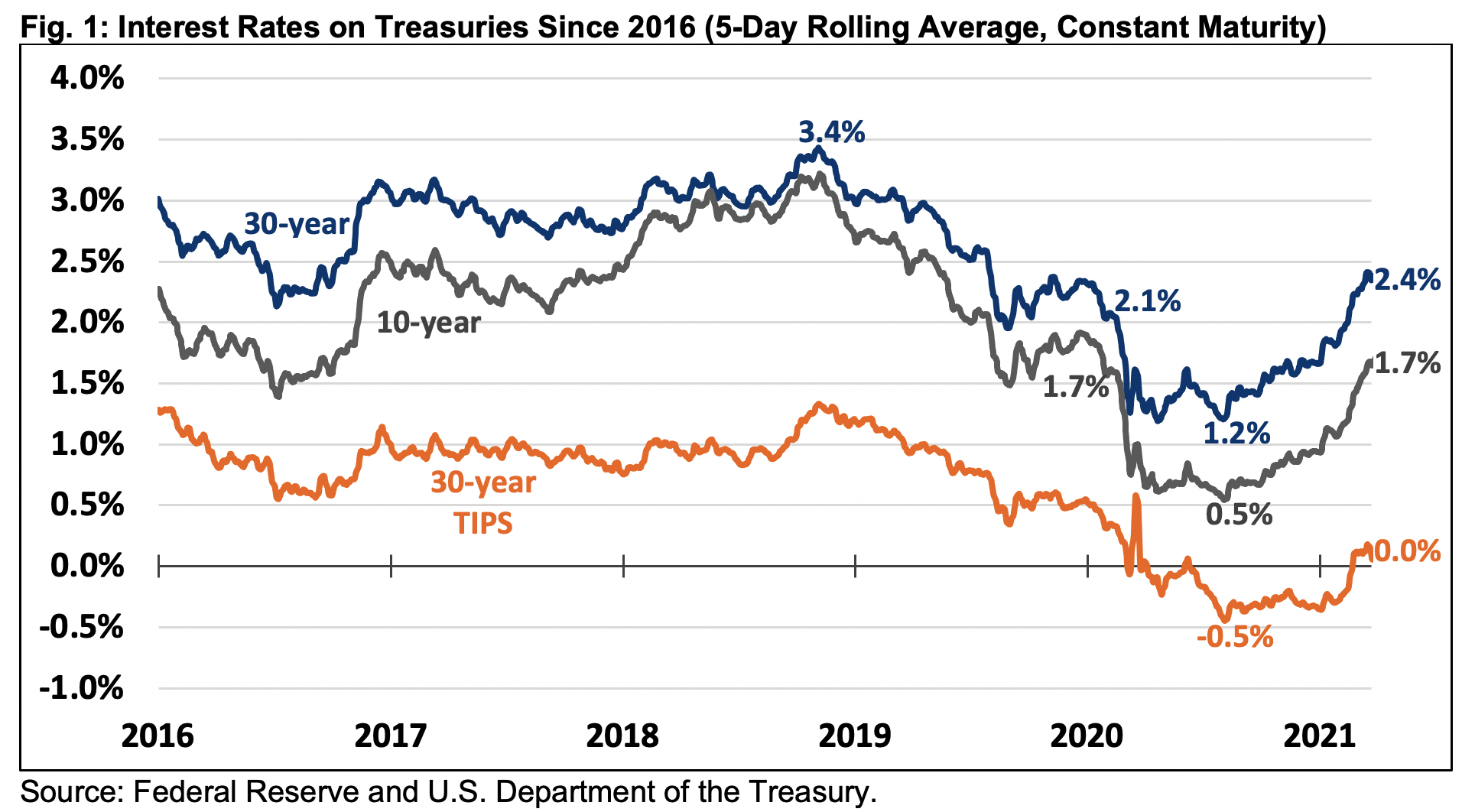

Interest rates across the Treasury term structure reached their most recent peak in 2018, then gradually fell over the course of 2019 and early 2020, and fell precipitously due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the fall of 2020, however, long-term rates have been rising toward their pre-pandemic levels, and they are projected to continue rising over the long term.

The COVID-19 pandemic, economic fallout, and subsequent policy response resulted in a deep but temporary decline in interest rates on all federal bond maturities. Thirty-year rates, which had already declined from a recent peak of 3.4 percent in 2018 to 2.0 percent in February 2020, dropped below 1.0 percent on March 9, 2020, and then remained between 1.2 percent and 1.8 percent through August 2020. Similarly, ten-year bond rates dropped from 1.5 percent in February 2020 to just above 0.5 percent on March 9, 2020, and then remained between 0.5 percent and 1.2 percent through the summer of 2020. Interest rates on short-term bonds – which are more directly influenced by Federal Reserve actions – all dropped from above 1.5 percent at the beginning of 2020 to below 0.1 percent on most days.

While short-term bond yields have remained low, long-term yields have been rising since last fall, especially between January and mid-March. Interest rates on ten-year bonds have risen from 0.7 percent in late September 2020 to 0.9 percent at the end of 2020, and to between 1.6 and 1.7 since the middle of March. Thirty-year bond rates have risen from 1.4 percent in late September 2020 to nearly 1.7 percent by the end of 2020, and to between 2.3 and 2.4 percent since March. Based on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) yields, this growth appears to reflect both higher real interest rates and an increase in inflation expectations.

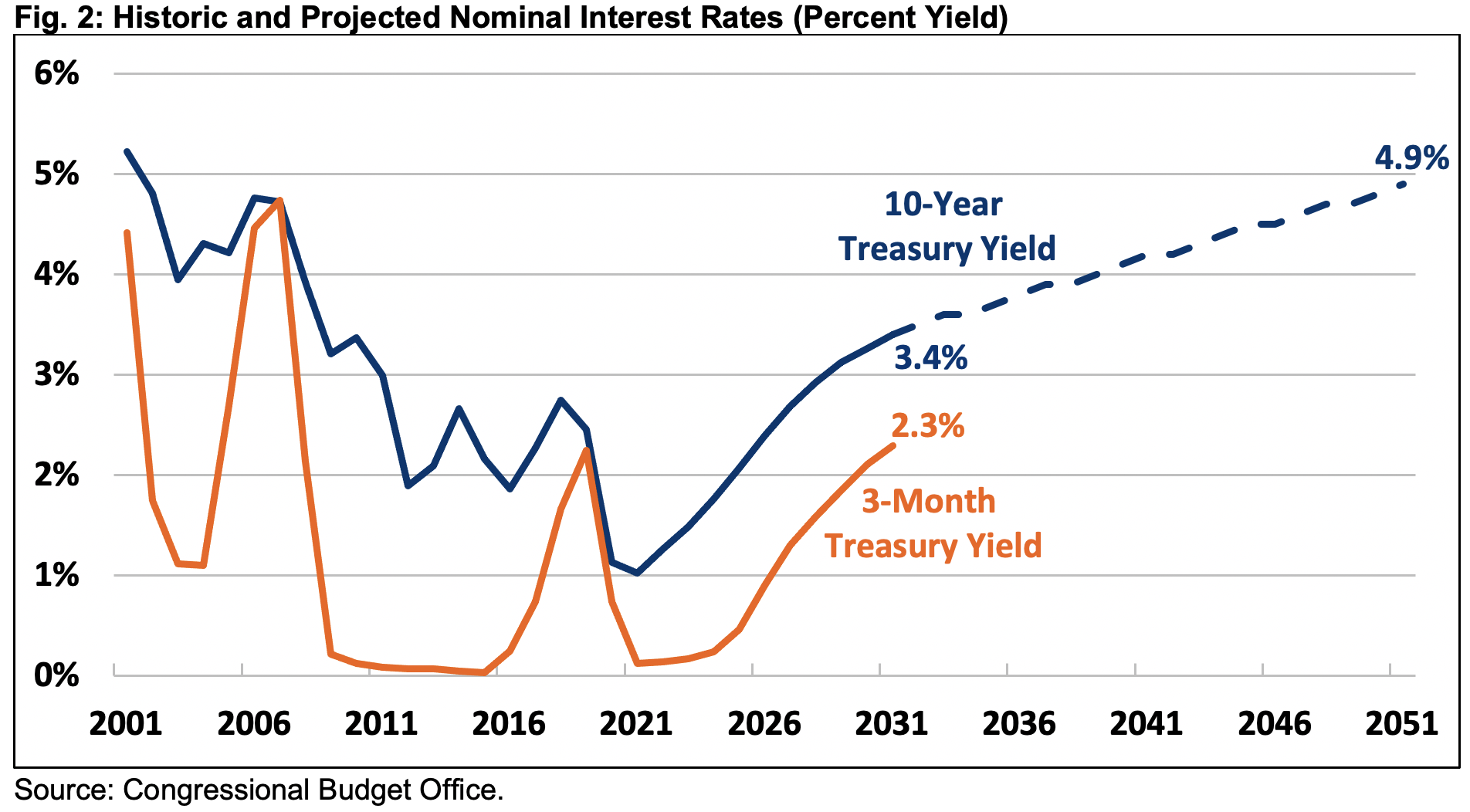

While the first quarter liftoff in interest rates was faster than anticipated, rates are expected to continue to rise over the long term under current law. In February, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected the interest rate on ten-year Treasury notes would rise from 1.1 percent this year to 2.1 percent in 2025, when CBO expects the economy to surpass its potential under its latest forecast, then rise further to 3.4 percent by 2031. Similarly, CBO projected the interest rate on three-month Treasury bills would rise from 0.1 percent this year to 0.6 percent in 2025 and to 2.3 percent by 2031. This rate will largely depend on the Federal Reserve’s response to inflation and employment data.

Beyond 2031, rates are projected to continue rising. In its latest Long-Term Budget Outlook, CBO projected the rate on ten-year bonds would grow to 4.2 percent by 2041 and 4.9 percent by 2051. These interest rate forecasts are based on projected levels of public debt, labor force growth, domestic and foreign savings, productivity growth, supply and demand for safe assets, share of income paid to capital, and inflation rates. Cyclical factors are excluded from interest rate forecasts.

Importantly, these projections are based on CBO’s March 2021 extended baseline and account for neither the effects of the recently-enacted $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, nor any future borrowing that might be undertaken for new priorities. Further borrowing would likely boost interest rates, though this would depend on the details of new spending increases or tax cuts.

As Interest Rates and Debt Rise, So Will Interest Costs

The COVID-19 pandemic-led decline in interest rates will temporarily reduce federal net interest payments – from $375 billion in FY 2019 to a projected low of $284 billion in 2023. These projections likely understate interest costs in light of the recent uptick in Treasury yields. If interest rates continue their upward trend, net interest payments could begin rising after 2023.

Under current law, net interest payments will more than double, rising from $284 billion in FY 2023 to $631 billion by 2029 and $846 billion by 2031. Under an alternative scenario that assumes policymakers extend most expiring tax cuts and grow annual appropriations with the economy rather than inflation, interest costs would more than triple, rising to $948 billion by FY 2031.

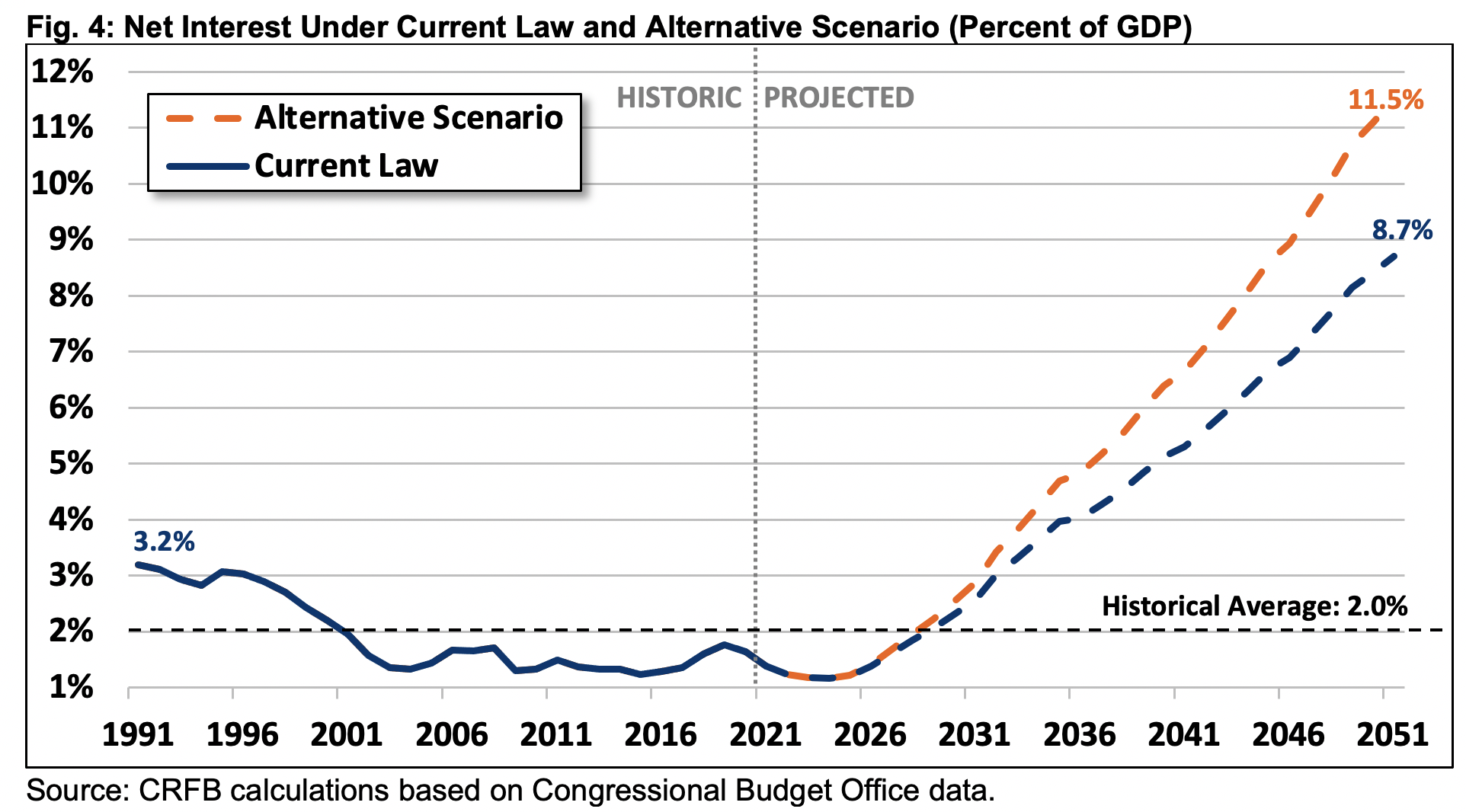

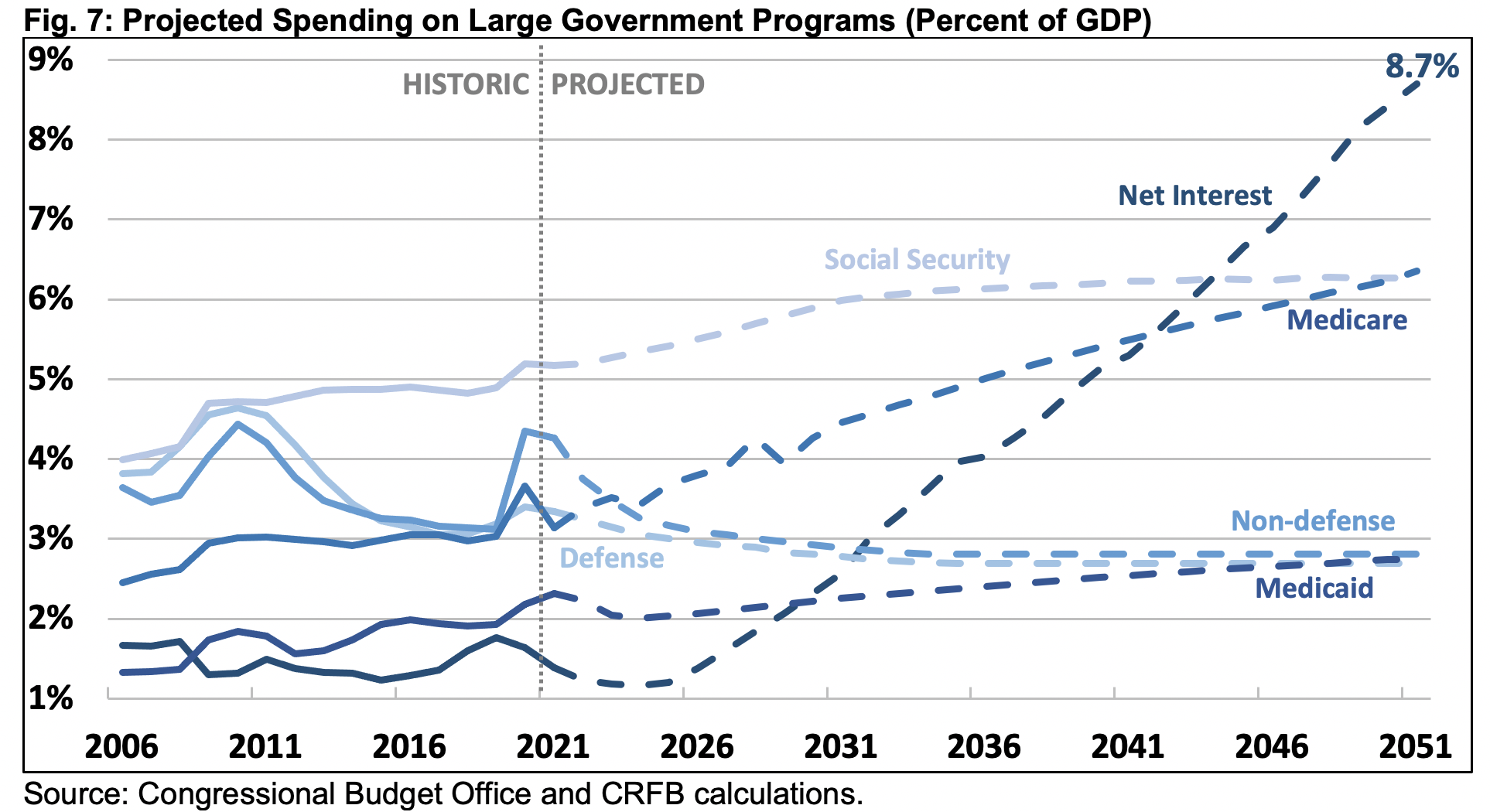

As a share of the economy, net interest costs will decline to a low of 1.2 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in FY 2022 and remain at that level through 2025 before rising to 2.6 percent of GDP by 2031. Over the long term, interest payments will grow to 5.3 percent of GDP by 2041 and 8.7 percent of GDP by 2051. Under the alternative scenario, interest costs would rise to 2.9 percent of GDP by 2031, 6.7 percent of GDP by 2041, and 11.5 percent of GDP by 2051. By comparison, interest payments have averaged 2.0 percent of GDP over the past 50 years and peaked at 3.2 percent of GDP in 1991.

Understanding the Decline in Long-Term Interest Rates

While the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a sharp interest rate contraction, rates have generally been trending downward for the last four decades. For example, the ten-year Treasury yield averaged 12.2 percent in the first half of the 1980s, but fell to 8.5 percent by 1990, 6.0 percent in 2000, 3.2 percent by 2010, and leveled off at an average of 2.3 percent in the second half of the 2010s.

About 40 percent of this ten-point drop in interest rates can be attributed to both lower inflation and lower inflation expectations. However, even real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates fell by roughly six percentage points between the 1980s and the late 2010s. Half of that decline took place during the 1994-2005 period. Importantly, interest rates around the world have also been falling.

A number of theories and factors can help explain this decline, including changes in monetary policy, slower productivity growth, population aging, increased international capital flows, a global savings glut, increased demand for safe assets, declining global investment, and cyclical factors. Some have also suggested the “secular stagnation” theory as a possible explanation.

At least three studies have aimed to disaggregate these effects, including a paper by Edward Gamber at CBO, a piece by Ernie Tedeschi, and a paper by Larry Summers and Lukasz Rachel. While each study looks at different time periods, all conclude that weaker economic growth – driven by slower productivity and an aging population – have played a substantial role.

In addition, all three studies concluded that a rising debt-to-GDP ratio has put upward pressure on interest rates, counteracting some (but not all) of the effects of the other factors. In part, this is why CBO projects interest rates to trend upward in the coming decades but remain well below their peak in the early 1980s. These projections come with a wide degree of uncertainty.

Interest Payments Are a Costly Part of the Federal Budget

Every dollar spent on interest on the debt is a dollar unavailable to fund new spending priorities, reduce taxes, or decrease budget deficits. In our recent paper, How High are Federal Interest Payments?, we showed that interest costs remain high even at today’s low rates.

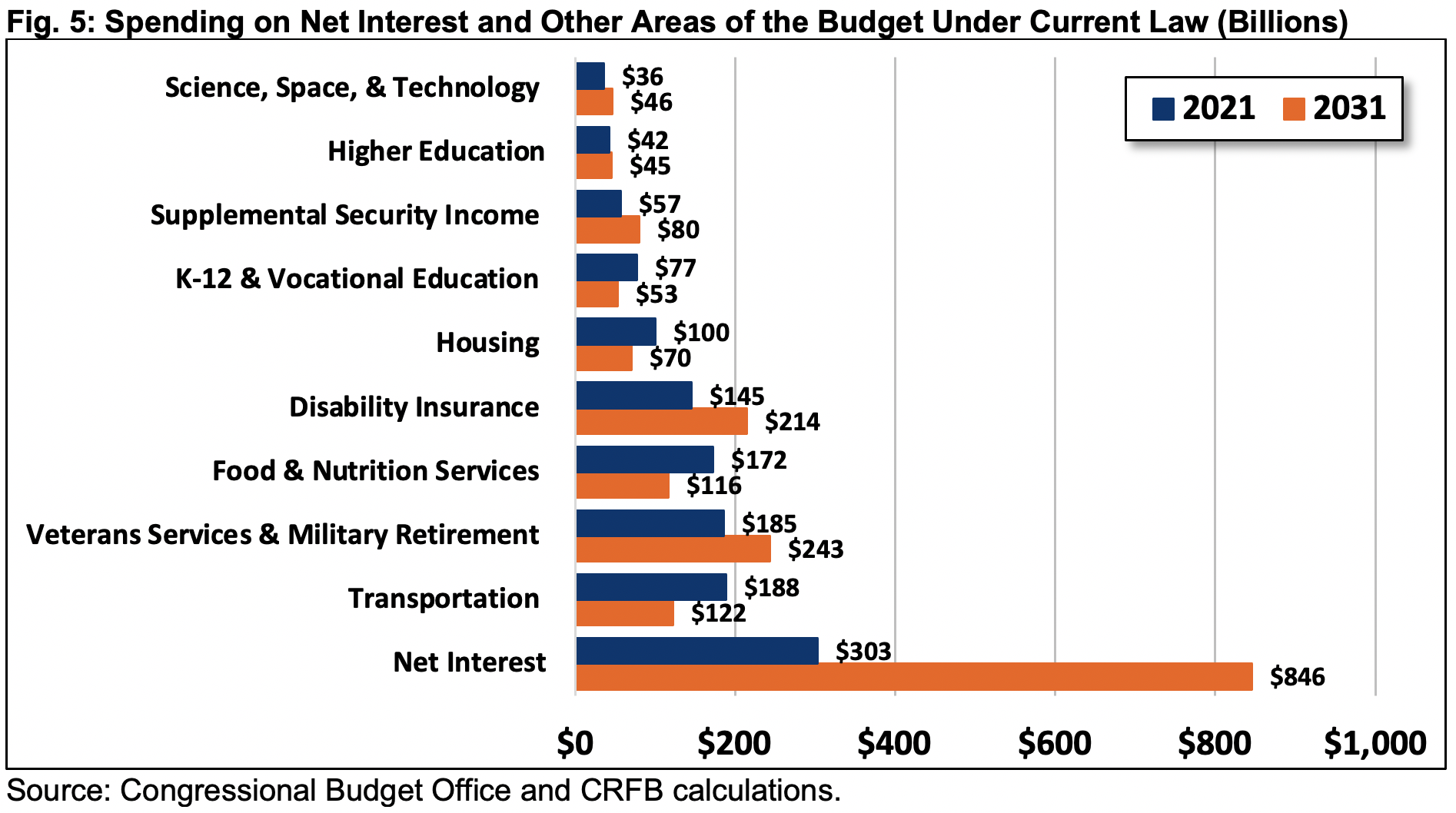

The roughly $300 billion the federal government will spend on interest payments this fiscal year is more than it is expected to spend on veterans’ services and military retirement ($185 billion); transportation ($188 billion); food and nutrition services ($172 billion), including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (“food stamps”); housing ($100 billion); K-12 and vocational education ($77 billion); and higher education ($42 billion). By FY 2031, interest costs are projected to be larger than federal spending on Medicaid and unemployment compensation, and over 90 percent as large as defense spending.

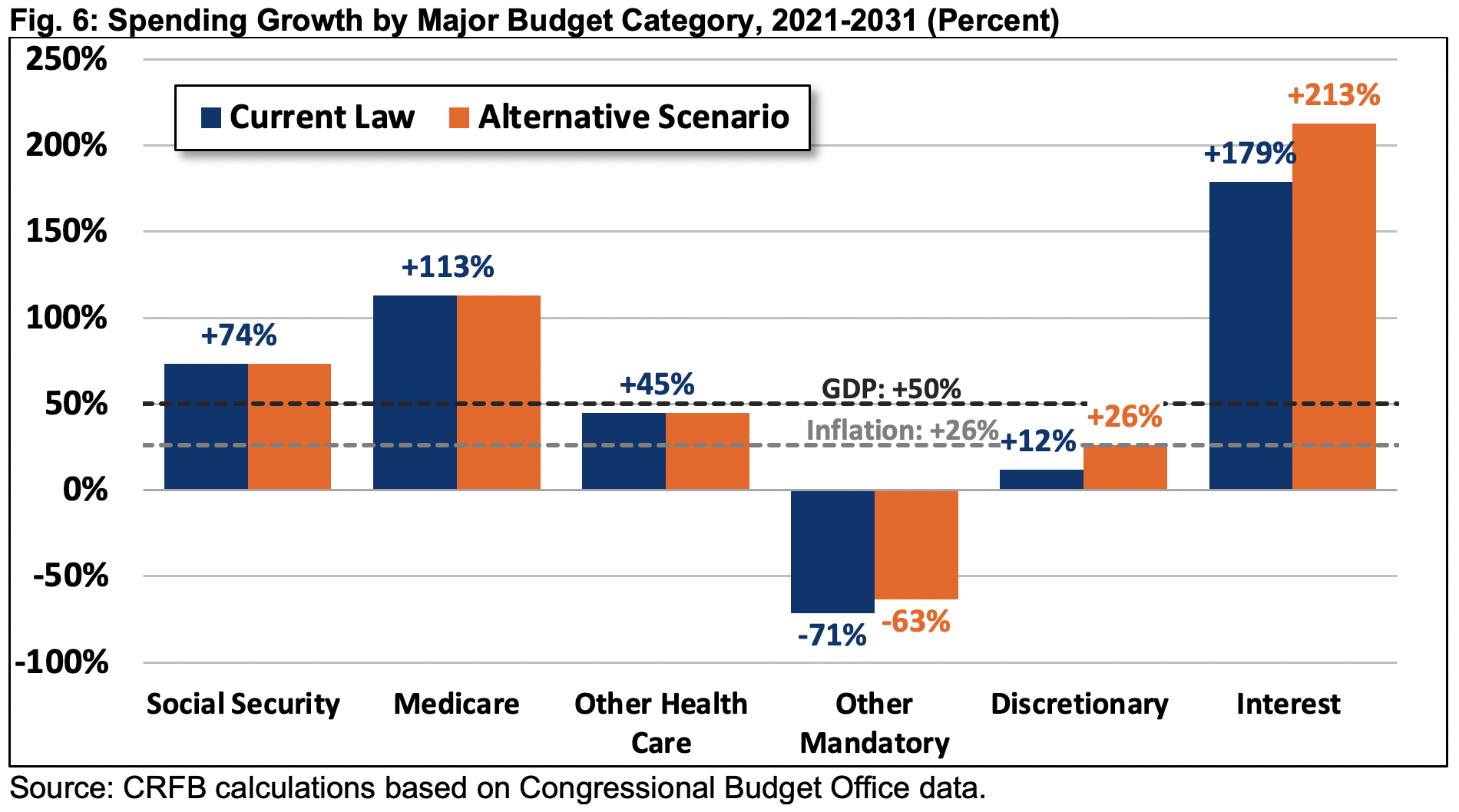

Over the next decade, interest will be the fastest growing part of the federal budget. By the end of the decade, interest costs will nearly triple. They will grow at nearly four-times the pace of growth in spending on Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and health insurance exchange subsidies, and over three-times the pace of growth in the economy. Meanwhile, Medicare costs will more than double, Social Security spending will grow by roughly three-quarters, and most other spending will grow slower than the economy or, in some cases, shrink.

Over the long term, interest costs will continue to outpace growth in other areas of the budget. Interest will exceed total non-defense and defense discretionary spending by FY 2032 and will go on to become the largest federal government line item – exceeding the cost of Social Security and Medicare – by 2045. By that point, spending on net interest will consume about 90 percent of all individual income tax revenue.

Higher Interest Rates Would Further Increase Interest Costs

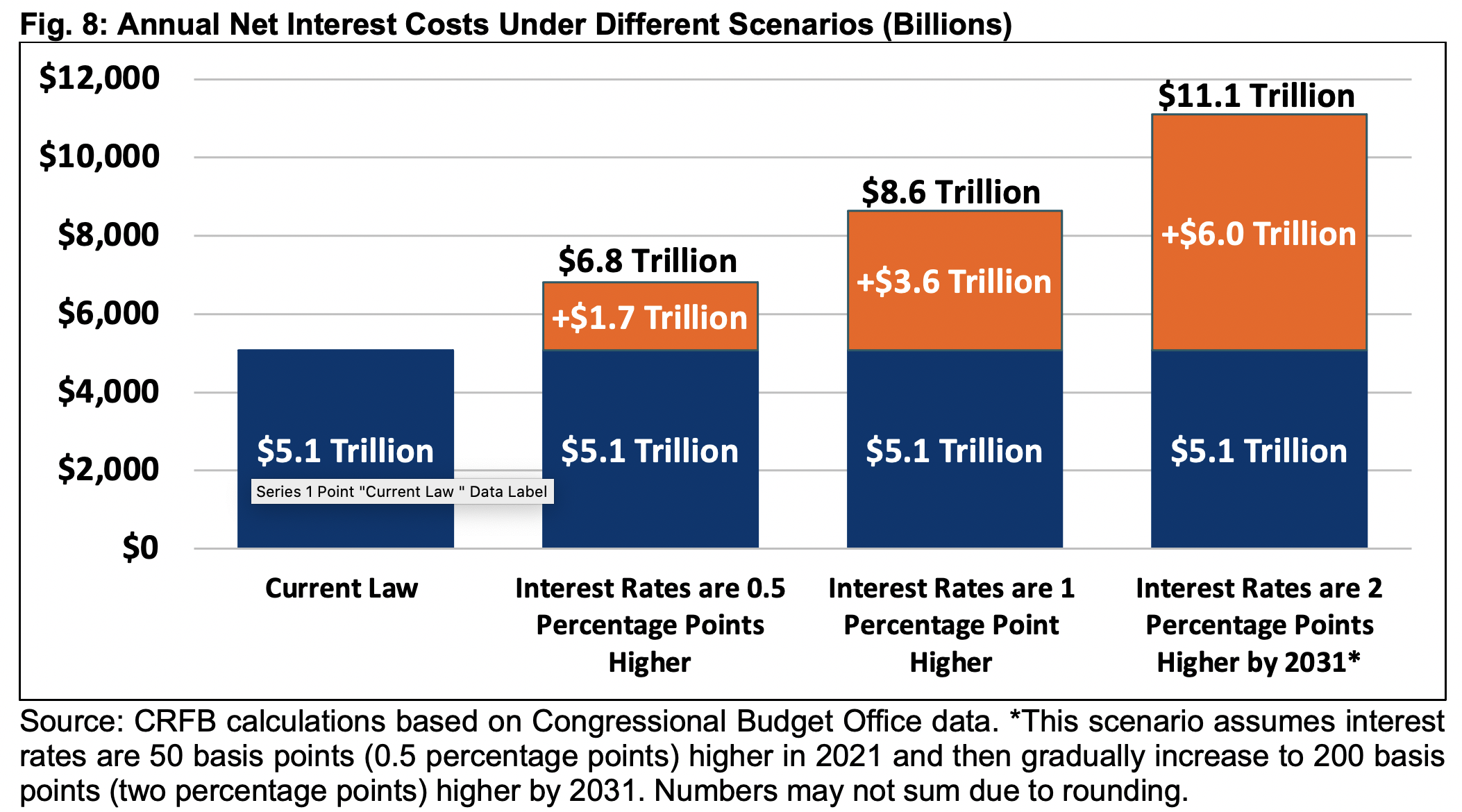

At about 1.6 percent, the interest rate on ten-year Treasury notes is currently about 50 basis points (or 0.5 percentage points) higher than CBO projected it would be this quarter. While interest rate projections are highly uncertain, should they continue to outperform CBO’s projections, the result will certainly be more debt and more spending needed to service that debt.

Under current law, we project interest spending will total $5.1 trillion over the 2021 to 2031 budget window. If interest rates on the projected annual debt stock were 50 basis points (0.5 percentage points) higher than CBO currently projects – reflecting the continuation of the current disparity between projections and reality – interest costs would increase by $1.7 trillion, to $6.8 trillion total. If interest rates were 100 basis points (one full percentage point) above CBO’s forecast, interest costs would total $8.6 trillion over that period, which is a $3.6 trillion increase over current law.

If interest rates begin at 50 basis points (0.5 percentage points) above CBO’s projections and gradually rise to 200 basis points (2 percentage points) above CBO’s forecast – bringing ten-year rates to just above their 30-year average of 4.3 percent by 2031 – interest costs would total $11.1 trillion over the 2021-2031 budget window, which is $6.0 trillion more than under current law.

Conclusion

As the national debt continues to grow at an unsustainable rate, federal interest payments on that debt will inevitably rise. And if interest rates rise from today’s low levels as projected, interest payments will rise quickly, increasingly crowding out other important priorities.

CBO’s projections of rising interest rates are based on underlying economic and demographic variables, but they come with a high degree of uncertainty. Interest rates could remain substantially below CBO’s forecasts or come in substantially higher.

Yet, even under today’s low rates, interest payments are the fifth-largest line-item on the federal budget, consuming nearly one-tenth of all federal revenue. If rates and debt grow as projected, interest will ultimately become the single largest federal government line-item by 2045.

High and rising debt can both drive interest rates higher and leave the country more susceptible to future interest rate increases or spikes. The best insurance against the risk of rising interest rates is a sustainable fiscal outlook where debt is not growing relative to the size of the economy.

Once the pandemic and economic crisis are behind us, revenue and spending reforms will be needed to bring the fiscal situation under control.