Can Tax Reform Generate 0.4% Additional Growth?

Well-crafted tax reform would improve economic growth. While pro-growth tax reform can generate some revenue to the Treasury from the added growth, as we’ve shown before, tax cuts don’t pay for themselves.

In the recent tax debate, a number of lawmakers and advocates have made a seemingly more modest claim – that tax cuts and reform can accelerate the economic growth rate by 0.4 percentage points or more per year and thus pay for the tax cuts currently under consideration. In reality, however, 0.4 percentage points more of annual growth will likely cover less than two-thirds of the House or Senate tax plans’ $1.4 trillion cost; and less than one half of the $1.9 trillion true cost, if various expiring provisions continue.

Additionally, while 0.4 percentage points might sound small, such an increase in growth is highly unlikely to materialize as a result of tax reform alone.

In this paper, we show:

- Reasonable estimates of the current tax proposals will likely increase growth by no more than 0.1 percentage points per year on an ongoing basis.

- Official government estimates of past tax reform proposals have never found a dynamic response as large as 0.4 percentage points per year.

- Rosy estimates of the House and Senate tax plans that suggest they could achieve a 0.4-point hike in the annual growth rate make the heroic assumptions of ignoring the cost of higher debt and assuming permanence.

- Even increasing the growth rate by 0.4 percentage points would not be enough to offset the cost of the House and Senate tax cuts.

The current momentum for tax reform, which has not occurred in more than three decades, is an important and historic opportunity. It should not be squandered on a plan that would increase the already-unsustainable national debt, thereby undermining the very growth it is trying to create.

Moreover, even thoughtful and fiscally-responsible tax reform is unlikely to achieve the 0.4-percentage-point annual growth boost that some are claiming unless it were combined with other pro-growth reforms such as changes to entitlement programs, immigration policy, regulatory reform, and controlling the national debt.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Will Likely Increase Growth by 0.1 Points or Less

The lower marginal tax rates, base broadening, and other changes in the House and Senate versions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) should help improve economic growth by increasing competitiveness and incentives to work and invest. However, higher levels of debt from the bills' $1.4 trillion costs will reduce any growth impact.

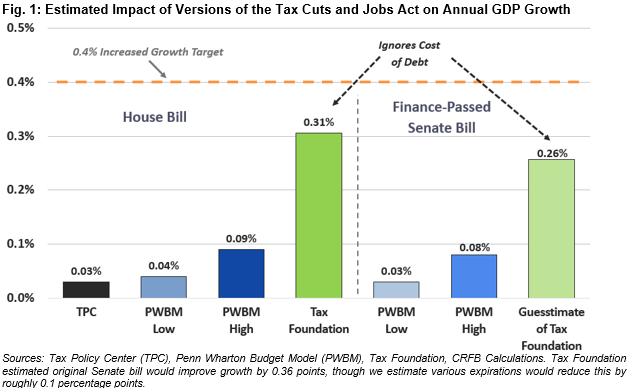

Outside organizations have produced a number of dynamic analyses of various versions of the TCJA. So far, no estimate that accounts for the economic impact of higher debt has found the bill would raise the growth rate by more than 0.1 percentage points per year. Rather, estimates of the growth boost range from 0.03 to 0.09 points per year – not even a quarter of the 0.4-point target.

For example, the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) – which employs a model similar to those used by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) – has found different versions of the TCJA would improve growth by between 0.03 and 0.09 percentage points per year. Likewise, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates the House bill would increase average annual growth by 0.03 points over the budget window, largely due to a short-term increase in output that dissipates over time.

Only the Tax Foundation, whose model ignores the cost of debt and incorporates other optimistic assumptions, projects the increase to average annual growth would rise by more than 0.1 percentage points. Their estimate of the House bill suggests it would raise growth by about 0.3 percentage points, and when they update their analysis of the revised Senate bill (incorporating its numerous expirations), they are likely to find that it will produce even less growth.[i]

No Previous Tax Plan Would Boost Growth by 0.4 Points Per Year

The TCJA could be made more pro-growth by further scaling back distortive tax breaks, making expiring policies permanent, and reducing the revenue loss. However, even the best-designed tax reforms are unlikely to produce the 0.4-point increase in the growth rate many have claimed.

The professional staffs at the Treasury Department's Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) and at JCT have produced numerous dynamic analyses and estimates over the years, and to our knowledge, they have never estimated that any tax reform plan would increase economic growth by 0.4 percentage points per year over a sustained period. (A one-time boost of 0.4 percentage points or more in the first few years is reasonable, to the extent tax cuts generate temporary Keynesian stimulus.)

The best growth estimate we are aware of from an official government estimator comes from Treasury's assessment of a low-rate progressive consumption tax, which they found could increase Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 0.2 to 2.3 percent in the first decade and would generate a 0.03 to 0.22 percentage point increase in the annual growth rate over two decades. Most estimates for traditional income tax reforms suggest growth that is much more modest.

Fig. 2: Dynamic Estimates of Past Tax Plans

| Tax Reform Plan | Increase in Long-Run GDP | 10-Year Change in GDP | Increase in Avg. Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBO, 2004: 10% Across-The-Board Tax Cut | -1.5% to 0.6% | 0.0% to 1.1%* | 0% to 0.14% |

| JCT, 2005: Deficit-Financed Ind. Income Tax Rate Cut | -0.6% to -0.2% | 0.0% to 0.5%* | 0% to 0.06% |

| JCT, 2005: Deficit-Financed Corporate Tax Rate Cut | 0.0% to 0.3% | 0.2% to 0.4%* | 0.02% to 0.05% |

| Treasury, 2006: Growth and Investment Tax Plan | 1.4% to 4.8% | 0.1% to 1.9%† | 0.02% to 0.18%^ |

| Treasury, 2006: Progressive Consumption Tax | 1.9% to 6.0% | 0.2% to 2.3%† | 0.03% to 0.22%^ |

| Treasury, 2006: Simplified Income Tax | 0.2% to 0.9% | 0.0% to 0.4%† | 0% to 0.04%^ |

| JCT, 2006: Illustrative Rev-Neutral Ind. Tax Reform | 0.2% to 3.5% | 1.1% to 1.9%* | 0.14% to 0.24% |

| JCT, 2011: Illustrative Rev-Neutral Ind. Tax Reform | 1.1% to 1.6% | 0.8% to 1.1%* | 0.10% to 0.14% |

| JCT Staff, 2011: Illustrative Rev-Neutral Corp Cut | 0.3% to 0.4% | 0.2%* | 0.02% |

| JCT, 2014: The Tax Reform Act of 2014 | N/A | 0.1% to 1.4%* | 0.01% to 0.17% |

Estimates for the GDP increase in the 10th year are not available. Figures with a * show the average increase in GDP over the last five years of the budget window, while figures with a † show the average increase over the entire budget window.

^ = Annual average growth rates estimated based on the change in GDP in year 20. For all other studies, average annual growth rate estimates assume the average increase in GDP over the last five years reflects the increase in GDP in the eighth year.

Claims that tax reform will generate 0.4 percentage points more of growth generally come from cherry-picking data. For example, a recent letter from several prominent conservative economists seems to suggest such an increase is possible because the Treasury Department previously estimated a 2005 tax reform plan would increase GDP by about 4.8 percent. However, 4.8 percent was a long-run estimate (after well more than 20 years), was the high end of a range (1.4 to 4.8 percent), and was in regards to a much more comprehensive and pro-growth plan (unlike the TCJA, it was revenue neutral and included permanent full expensing).

In reality, Treasury estimates suggest that the 2005 plan would increase the average annual growth rate by between 0.02 and 0.18 percentage points per year over two decades – far short of the 0.4-point goal.

Most Rosy Growth Estimates Ignore the Cost of Debt

While no outside models project that the current tax bills will increase the annual growth rate by 0.4 percentage points over the first 10 years, those that come closest do so in part by assuming away the economic cost of debt.

When the government issues new debt, it must be purchased from increased foreign investment, higher domestic savings, or a shift in domestic savings away from private investments. This shift is known as "crowd out,” and over time it leads to lower private investment and therefore slower economic growth.

Most sophisticated modelers assume a mixture of higher savings, increased foreign investment, and crowd out absorbs higher debt – consistent with substantial evidence that all three are occurring. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for example, assumes that a $1 increase in deficits leads to $0.33 in private investment being crowded out. In other words, roughly one-third of new debt is purchased in place of productive private investments. Thus, higher debt has some negative impact on economic growth.

By necessity or by choice, however, some models ignore the cost of debt altogether – assuming higher debt has zero effect on the economy. The Tax Foundation, for example, assumes zero crowd out due to an unlimited supply of foreign capital – even though their own critique of crowd out admits there is some cost to higher debt, and the studies they cite suggest the cost is significant. Economist Larry Kotlikoff's GGM model, meanwhile, assumes tax cuts have no direct debt impact because they are immediately offset with more efficient tax increases.

The analysis by the President's Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) looks only at the benefit of the lower rates without considering the mitigating economic impact of higher debt or various base-broadening measures that would indirectly increase effective tax rates. (CEA’s high-end growth estimate also assumes permanent expensing when the Unified Framework calls only for temporary expensing.)

Fig. 3: Treatment of Debt in Different Rosy Dynamic Analyses

| Model | Treatment of Debt |

|---|---|

| Tax Foundation | Assumes an unlimited supply of potential savings |

| CEA Analysis | Considers only the benefits of tax cuts and ignores the cost of financing |

| Kotlikoff-GGM | Assumes tax cuts are immediately paid for with more efficient tax increases |

| OLG Models | Assume future deficits are offset with future spending cuts or tax increases |

| Memo: CBO | Assumes every $1 in additional deficits crowds out $0.33 in private investment |

Even some models used by scorekeeping agencies understate (though they do not ignore) the negative impact of debt. Overlapping Generations (OLG) models used by CBO, JCT, and others require debt to be stable over the long run. Therefore, these models generally assume future deficit reduction to offset new debt from tax cuts – and in doing so they generally overstate the benefits of tax cuts. Most of the high-end estimates in Fig. 2 are generally based on OLG models.

Even Boosting Growth 0.4 Percentage Points Would Not Offset the Tax Bills

There is no evidence to suggest the House or Senate tax bills will increase economic growth by anywhere close to 0.4 percentage points per year on a sustained basis. Yet even if they did, it still would not be enough to offset the proposals’ $1.4 trillion costs. Based on CBO's rule of thumb, 0.4 percent faster growth would generate roughly $1 trillion – slightly less than two-thirds of the tax bills' costs. To fully pay for either bill, tax reform would need to increase the growth rate by nearly 0.6 percentage points, and by nearly 0.8 percentage points to offset the their cost assuming expiring provisions are made permanent and other gimmicks are removed.

The actual necessary increase in growth is almost certainly larger because CBO’s rule of thumb does not apply to tax-cut generated growth. While lower tax rates promote economic growth, they also reduce the share of that growth taxed by the federal government; meanwhile, higher debt further reduces feedback by increasing interest rates and other federal payments. In fact, PWBM estimates tax reform would have to increase annual growth by about 0.75 percentage points to offset the revenue loss of the amended Senate TCJA (that number would likely be closer to 1 point if all gimmicks were removed, or above 0.55 points if policymakers keep the bill’s gimmicks and use the current policy gimmick to reduce their revenue target).

No dynamic estimates of the tax bills find that they are even close to deficit neutral. The PWBM and TPC dynamic models find the bills will still cost $1.27 trillion to $1.7 trillion. While the Tax Foundation’s score of the current Senate bill may be less than $1 trillion, their estimates do not account for the economic cost of debt or the spending impact of higher growth.

Conclusion

Increasing growth by 0.4 percentage points on a sustained basis might sound doable, but such an increase actually means raising projected growth rates by more than one-fifth and is unlikely to occur because of tax reform alone.

Certainly, policymakers should work toward enacting reforms to improve economic growth by as much as possible, and tax reform is one critical piece of a comprehensive growth plan. But the tax reform plan under consideration is unlikely to generate more than 0.1 percentage points of increased growth per year, and over the long run it may actually slow economic growth. Lawmakers should not pretend otherwise but should instead both work to improve the bill and enact other pro-growth policies, including improving the debt trajectory, entitlement reform, regulatory reform, and labor market improvements. Here are some policies that might help.

Well-designed tax reform that broadens the base, lower rates, and improves our fiscal situation should be a part of this growth strategy; such reform would boost growth and in the process generate additional government revenue. But fiscally-irresponsible tax cuts do not pay for themselves, and tax reform in its current form will not boost growth by enough to avoid significant increases to the already too high national debt.

Note: on 11/27 we corrected a typo stating it would take nearly 0.9 percentage points of growth to offset the bills cost assuming expiring provisions are made permanent and other gimmicks are removed. It is nearly 0.8 percentage points

[i] At the time of publication, the Tax Foundation had not scored the most up-to-date version of the Senate bill. They did score the original version as presented by Senate Finance Committee Chairman Hatch. They found that the bill would increase annual growth rates by about 0.36 percentage points. The current Senate bill, however, introduced significant policy sunsets to make it Byrd Rule compliant. The Tax Foundation has indicated that temporary policies do not increase growth nearly as much in their model as permanent policies. Therefore, we “guesstimate” that based on the Tax Foundation’s score and the sunsets in the bill as reported by Senate Finance, the growth effects of a new Tax Foundation score would be about 0.1 percentage points less.