Can a Carbon Tax Fund Climate Investments?

Though the Senate will not consider the House-passed Build Back Better Act (BBB), there has been some discussion of reviving the legislation’s climate provisions as part of a new package that would also be designed to promote energy independence, reduce prescription drug costs, raise revenue, and reduce deficits.

The House-passed Build Back Better Act financed spending and tax breaks through a combination of tax increases on corporations and high earners, prescription drug savings, and near-term borrowing (along with arbitrary policy expirations).

In this analysis, we consider the implications of coupling the Build Back Better Act’s climate provisions with a carbon tax or other carbon pricing mechanism. We rely heavily on helpful modeling from Energy Innovation: Policy & Technology LLC for this analysis. 1 Based largely on modeling from Energy Innovation, this analysis finds:

- The Build Back Better Act’s climate provisions would cost roughly $550 billion over ten years and would reduce net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 17 percent in 2030 compared to a “business as usual” scenario.

- A $20 to $40 per-metric-ton carbon tax, indexed to grow 1 to 5 percent faster than inflation annually, would raise $650 billion to $1.55 trillion of new revenue over a decade and reduce GHG emissions by 14 to 21 percent in 2030.

- Incorporating interactions, a $20 per-metric-ton carbon tax would more than pay for the BBB climate provisions over a decade and generate long-term deficit reduction, while reducing GHG emissions by 25 percent in 2030.

- A $40 per-metric-ton carbon tax coupled with the BBB climate provisions would reduce deficits by $900 billion on net over ten years, save more in the second decade, and reduce GHG emissions by 30 percent in 2030.

Put simply, financing climate investments with a carbon tax could greatly improve their effectiveness in reducing emissions while leaving other revenue and spending offsets available to reduce deficits or fund other priorities.

Climate Provisions in the Build Back Better Act

The House-passed Build Back Better Act includes roughly $550 billion of spending and tax breaks designed to support clean energy and reduce carbon emissions.

Approximately $325 billion of these provisions are on the tax side of the ledger. To support clean electricity and renewable energy, the BBB would extend and expand several existing tax credits through 2026 while creating a few new tax credits, and then transition to a new, technology-neutral tax regime through 2031. The plan also includes new and expanded tax credits to support the purchase of various types of Electric Vehicles (EVs) and to promote energy efficient systems in homes and buildings, among other tax provisions.

The plan also includes $225 billion of increased spending. It would reduce air pollution and emissions from buildings through grants for installing low-emissions technologies. It includes funding for soil conservation, restoration of forests, and safe drinking water. The BBB would invest billions in building out EV charging networks, electrifying the federal vehicle fleet, building out passenger rail, and improving the climate resilience of critical infrastructure.3

The bill also includes a “green bank” program to help communities finance renewable energy projects and funds to help rural electric cooperatives transition to renewable energy sources. It includes additional funding for a “Civilian Climate Corps” and to fund research and development of new green technologies.

Not included in $550 billion of climate spending and investments is roughly $20 billion of climate-related offsets from a methane fee, Superfund tax, and leasing for offshore wind energy facilities.

The Fiscal Implications of Climate Action

The major climate provisions in the House-passed Build Back Better Act would cost roughly $550 billion, enough to increase debt by 1.8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2031 if not offset (the bill did include offsets, though also numerous budget gimmicks). A $20 per-ton carbon tax would fully pay for this spending; a $40 per-ton tax would generate substantial net savings.

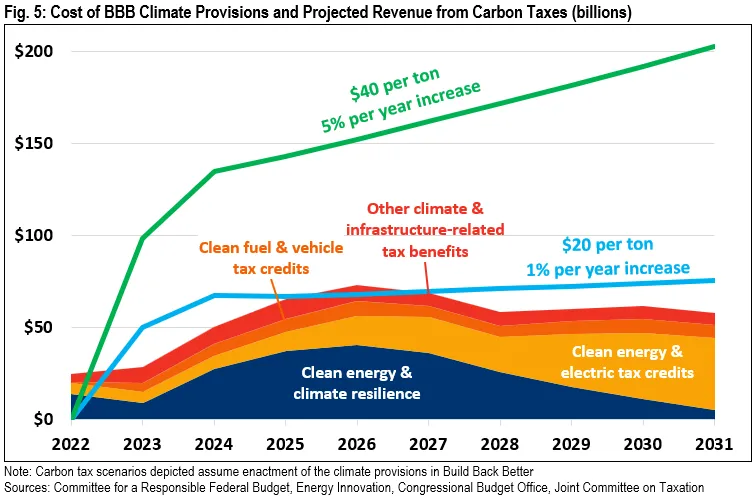

Based in part on modeling from Energy Innovation, we estimate a broad $20 per-metric-ton carbon tax, beginning in 2023 and growing one percentage point faster than inflation annually, would generate $650 billion of new revenue through 2031.4 A similar carbon tax starting at $40 per-ton and growing five percentage points faster than inflation would generate $1.55 trillion.5

Importantly, the BBB climate provisions would lower taxable emissions, resulting in less revenue from a carbon tax than if it were enacted on its own. Still, we estimate the $20 per-ton carbon tax would be more than sufficient to fully offset the BBB climate provisions’ cost over a decade. The $40 per-ton carbon tax in combination with BBB would raise roughly $900 billion.

While both versions of the carbon tax would fully fund new climate spending, the more aggressive version would also generate additional revenue, which policymakers could use for a variety of purposes. For example, $900 billion would be enough to reduce debt by 3 percent of GDP in 2031, replace the gas tax and make the Highway Trust Fund permanently solvent, issue a $265 per-person annual rebate, or cut the payroll tax rate by 1.2 percentage points.6

Both versions of the carbon tax would, in combination with the BBB climate provisions, reduce deficits in the second decade. Since much of the climate spending represents one-time investments and many of the tax breaks are designed to be temporary, costs will decline over time. Meanwhile, carbon tax revenue is likely to continue growing throughout the second decade.

The Environmental Implications of Climate Action

Both the Build Back Better Act’s climate provisions and the carbon taxes we’ve described would reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, which scientists have found to be a driving force behind climate change. Their effects would be even stronger if enacted in combination.

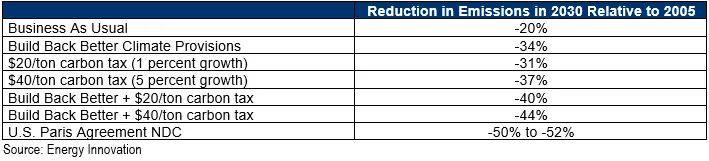

Energy Innovation estimates the BBB climate provisions would reduce 2030 net GHG emissions by around 17 percent compared to a “business as usual” baseline, from roughly 5.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide and equivalent (CO2e) emissions to 4.5 million metric tons.7 This would bring the United States almost halfway toward its Paris Agreement goal of reducing 2030 emissions to less than 50 percent of 2005 levels.8

By comparison, Energy Innovation finds that a $20 per-ton carbon tax, starting in 2023 and growing one percentage point faster than inflation annually (reaching $25 by 2030), would reduce emissions by 14 percent. A $40 per-ton tax, starting in 2023 and growing five percentage points faster than inflation annually (reaching $70 by 2030), would reduce emissions by 21 percent. On its own, the more aggressive carbon tax could bring the United States almost three-fifths of the way toward its Paris Agreement goal.9

Financing the BBB climate provisions through a carbon tax would further discourage the use of carbon-intensive products and services, encourage the adoption of cleaner alternatives, and incentivize the development of new technologies to reduce net emissions. Energy Innovation finds the combination of a $20 per-ton carbon tax and the BBB climate provisions would reduce 2030 emissions by 25 percent – more than two-thirds of the way to the United States’ Paris Agreement goal. The BBB provisions in combination with the $40 per-ton carbon tax would reduce 2030 emissions by 30 percent – nearly four-fifths of the way toward the Paris Agreement goal.

Conclusion

Financing the climate-focused provisions in the Build Back Better Act with a tax on greenhouse gas emissions would not only amplify their effect on emissions reductions, but also ensure they do not add to the national debt nor rely on revenue and spending provisions that could otherwise be used for deficit reduction.

On their own, the Build Back Better Act’s climate provisions would cost $550 billion over a decade and reduce 2030 emissions by 17 percent, while the carbon taxes we examined would raise $650 billion to $1.55 trillion over ten years and reduce 2030 emissions by 14 to 21 percent.

When combined, the Build Back Better Act’s climate provisions and the carbon taxes could generate between $50 and $900 billion of savings over a decade and reduce 2030 emissions by 25 to 30 percent.

These results are preliminary and would change based on the model used and depending on a number of variables, including the carbon tax rate, base, and phase in as well as the details of any final climate or energy-focused tax break and spending package.

While climate change represents a serious threat to the security and prosperity of current and future generations, so too does our skyrocketing national debt. Lawmakers should commit to addressing the former without exacerbating the latter.

1 We want to thank Energy Innovation for modeling these scenarios. The BBB climate provisions estimates are based on their “moderate” scenario, which assumes 66 percent of electricity generation in 2030 will be from clean sources, 75 percent of EV sales qualify for bonus credits, 15.9 percent union representation for power plant construction, a domestic content share of 65.4 percent for electricity generated from solar photovoltaics, and 65.4 percent for electricity storage. The “moderate” scenario assumes 100 percent domestic content share for electricity generated from solar thermal, geothermal, and municipal solid waste. The carbon tax scenarios assume carbon pricing applies to all emissions of GHGs throughout the economy, including non-energy emissions from the manufacturing sector and non-CO2 GHGs. They include land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF), exclude bunker fuels, and assume a rebate for sequestered CO2. You can read Energy Innovation’s analysis of the BBB climate provisions in isolation here: Modeling the infrastructure bills Using the Energy Policy Simulator (energyinnovation.org)

2 These emissions reduction figures are relative to projected 2030 emissions under Energy Innovation’s “business as usual” scenario, and thus represent a reduction from the baseline. The Paris Agreement NDCs are determined relative to net 2005 emissions levels, with the United States aiming to reduce emissions by 50 to 52 percent relative to 2005 levels. Below are reductions relative to 2005 levels:

3 An earlier version of the Build Back Better Act included a program called the Clean Energy Performance Program (CEPP), which relied on a series of financial penalties and rewards to encourage power utilities to adopt certain clean energy standards. CEPP did not make it into the House-passed legislation.

4 Our analysis assumes the carbon tax indexing begins in 2022, so the actual tax rate in 2023 would be somewhat higher in nominal terms.

5 Different policy, economic, and modelling assumptions could lead to different results. Using a model aligned more similarly to the Congressional Budget Office’s methodology, we estimate these carbon taxes would raise $650 billion and $1.4 trillion, respectively. We rely on the Energy Innovation modelling so that revenue and emissions numbers are internally consistent. Different phase-in schedules could help to close the gap between revenue differences without substantially changing the emissions impact.

6 The deficit reduction estimate is based on a 2031 net savings figure of $970 billion, which includes $900 billion in primary savings and $70 billion in reduced interest payments.

7 The “business as usual” scenario holds current policy constant and assumes a 48 percent share of clean electricity generation in 2030.

8 These findings are broadly similar to other estimates. For example, the REPEAT Project estimates the BBB climate provisions would reduce emissions by 23 percent in 2030. The World Resource Institute estimates a similar package would reduce emissions by 17 percent.

9 Using a model more similarly aligned to CBO, we find these taxes would reduce emissions 13 percent to 31 percent.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-