6 Ways to Reduce Health Care Costs

By JOSH GORDON AND DARBIN WOFFORD

This journal article originally appeared in the Milken Institute Review.

Here’s some old news that, depressingly, remains relevant: rising health care costs are projected to continue straining the budgets of families, employers, states and the federal government. Despite policymakers being aware of this problem for years, we are as close as ever to the first domino falling: the Medicare trust fund is projected to become insolvent by 2028.

Handwringing, of course, is cheap. That’s why the Health Savers Initiative, a project of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Arnold Ventures and West Health, has worked to identify concrete policy options to make health care more affordable without reducing its quality.

In 2021 the United States spent a total of $4.3 trillion on health, double the amount in 2000 even after adjusting for inflation. That’s over 18 percent of GDP, or nearly $13,000 per person. At $1.3 trillion (along with another half trillion dollars in tax breaks), health care is the largest category of outlays in the federal budget and is projected to grow faster than any other except interest on the debt.

What’s more, this spending far outpaces the rest of the industrialized world as a portion of GDP. In 2017, the most recent year for which we have comparison data, the U.S. shelled out more than double the OECD average and nearly 50 percent more than the next highest spending country, Switzerland.

We’ve lived with health care inflation for a very long time, but something is going to have to give soon. With the population aging rapidly and technology adding ever more expensive measures to the medical toolkit, health care costs will crowd out other important public and private priorities unless we deliver it far more efficiently.

Here are six policy options, each with pieces drawn from bipartisan proposals, that would result in substantial savings for consumers and insurers, private and public.

Option 1: Reducing Medicare Advantage Overpayments

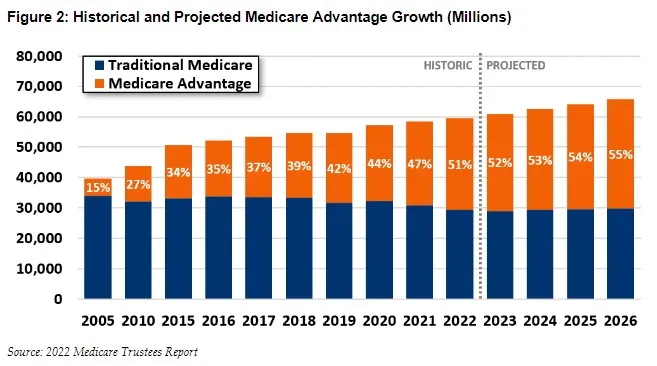

The Medicare Advantage (MA) program, which allows Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in federally funded private health insurance plans, is an increasingly popular alternative to traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare. Enrollment in MA has roughly doubled since 2010, with over half of Medicare beneficiaries now choosing private plans.

The original idea of Medicare Advantage was to make the Medicare maze both simpler to navigate and more comprehensive in what it provided, even as it saved Uncle Sam money through a combination of commercial insurance strategies and market competition. But in the free-for-all of American health care, no good deed goes unpunished: more than 100 percent of the savings have been pocketed by insurers. It now costs the federal government more, on average, for a beneficiary enrolled in an MA plan than it would if that same beneficiary were enrolled in FFS.

How could this be? MA plans are paid by the government based on estimates of how much fee-for-service Medicare costs to provide. But the MA plans are often able to wring out savings by negotiating lower reimbursement to providers and by reducing utilization of what they deem to be medically unnecessary services.

Now, commercial insurers typically devote much of those savings to lowering beneficiary cost-sharing and increasing benefits on things like dental, vision and hearing coverage — making them attractive options as they compete for clients in private markets. But the plans also have ways of gaming the payment structure that allow for more benefits and higher profits, and that wind up costing the government money.

The lion’s share of what are called overpayments stems from flawed risk adjustment in the payment system for MA plans. These plans are paid more for older and sicker enrollees and less for enrollees who are younger and healthier. That’s a normal feature in cost driven insurance markets. But with Medicare, risk adjustment is based primarily on the esoterica of physician diagnostic reporting (called “coding”), which gives MA plans powerful incentives to discover and code as much diagnostic information on enrollees as possible.

MA plans use a variety of strategies to report diagnoses. By contrast, similar reporting incentives don’t exist in FFS, where providers often code only enough to justify the use of the specific service for which the provider is seeking reimbursement. And this difference leads MA beneficiaries to appear sicker relative to FFS beneficiaries, which leads to higher payments. (The New York Times has written about how those strategies sometimes veer into fraud.)

Congress and the federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recognize the problem and have made some adjustments for coding intensity differences between MA and FFS. However, those adjustments fall short of the actual difference.

How do we know? You need not follow us very far into the analytic weeds since the explanation can be summed up succinctly. We used an adjustment protocol called the Demographic Estimate of Coding Intensity (DECI). The basic assumption underlying the DECI method is that, controlling for age, gender, etc., MA enrollees are no more in need of care as FFS beneficiaries. Indeed, the research suggests that Medicare Advantage enrollees are likely healthier.

Thus, even based on an assumption that may be too generous, we estimate that fully correcting for the gaming of coding intensity could save Medicare $370 billion over 10 years. About half of those savings would accrue to the Medicare Part A Hospital Insurance trust fund, thereby extending its solvency. In addition, Part B outpatient beneficiary premiums would be $57 billion lower.

Option 2: Equalizing Payments in Medicare Regardless of Site of Care

Within the uniquely inefficient U.S. health care system, hospital care is the largest single source of expenditures. Such high spending is, in part, driven by payment differences for virtually identical services based on the site of the treatment, regardless of safety or clinical effectiveness. This creates incentives to provide services in higher-cost settings, which are generally hospital-based locations instead of independent physician offices.

Importantly, these incentives encourage vertical integration with hospitals purchasing physician practices, nominally converting them to hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs), and thereby garnering higher payments. Between 2013 and 2018, the share of physician practices that were hospital-owned more than doubled. Today, at least one-third of physician practices are now hospital owned, and hospitals employ over 44 percent of all physicians. Because of these changes, the Congressional Budget Office has projected that fee-for-service payments to HOPDs will more than double over the next decade.

Another aspect of consolidation that is undesirable from the public’s perspective: vertical integration between hospitals and physician practices has increased the market power as well as the name-brand recognition of the big hospital systems. This allows them to bargain for even higher fee differentials (not to mention higher prices across the board) from commercial insurers who must account for patient preferences in creating preferred-provider networks. Maybe the worst part? There is substantial evidence that increased consolidation leads to inferior care.

Historically, there has been bipartisan political support for requiring Medicare to adopt site-neutral payments because it would reduce Medicare beneficiary premiums and cost-sharing, as well as total Medicare spending. It could also generate spillover savings for commercial insurers since Medicare’s stance could strengthen private negotiating leverage in moving toward site-neutral payment arrangements of their own. It would also reduce an incentive for hospitals to acquire physician practices. (For more about moving toward site-neutrality in commercial insurance, see Option 3.)

We estimate this policy change would cut federal deficits by $190 billion over 10 years. Medicare beneficiaries, for their part, would save $51 billion in lower premiums and $43 billion in reduced out-of-pocket cost-sharing, plus additional savings of $43 billion for mean between $30 billion and $90 billion in additional revenue collection over the period.

Option 3: Moving to Site Neutrality in Commercial Insurance Payments

The commercial market for health insurance suffers from site-based payment problems in part because insurers (and providers) often follow Medicare’s lead. The one big difference, though, is that Medicare can simply set the prices it pays for services. In the commercial market, insurers and their beneficiaries have limited pricing power, meaning they pay more than Medicare and must bear even more dramatic price differentials based on site-of-service.

The problems are two-fold. First, as with Medicare, the existence of payment differences based on site-of-service has led to an increase in the portion of services provided in the higher-cost settings — primarily on- and off-campus HOPDs. Second, as discussed earlier, the existence of wide payment differentials across sites in both Medicare and commercial insurance encourages provider consolidation. This increases the pricing power of the now-larger hospital systems, which can demand higher prices in negotiations with commercial insurers. (For more on high hospital prices overall, see Option 4.)

The Health Savers Initiative reviewed numerous services with the highest commercial payment differentials between independent physician offices and HOPDs, and our findings illustrate the problem in glaring terms. For example, the median payment for electrocardiogram monitoring in an HOPD is three times the fee when performed in a physician’s office. Relative payments for drug infusions are even higher, with HOPD fees 3.2 times higher than in physicians’ offices.

The first step to achieving commercial insurance site-neutrality would be to prohibit “off-campus” HOPDs — those not having an emergency department and located more than 250 yards from their hospital’s main campus — from billing add-on fees associated with hospital affiliation. This would require changes to federal rules governing billing and administrative complexity. Currently, hospitals that own physician practices (re-labeled as off-campus HOPDs) are allowed to charge facility fees on top of the fees they charge for actual physician services. And along with inflating total prices, they create confusion for patients receiving separate bills.

The single fee created in this first remedial step for each service provided in an off-campus HOPD would then be capped at the median paid for those same services when provided in an independent physician’s office. This, by the way, is similar to the approach already taken to calculate laboratory fees under Medicare. In addition, the median could be calculated for specific geographic areas to account for differences in regional costs. A final step could extend payment rate caps to all oncampus HOPDs as well. Those caps would only apply to services that are low-complexity and thus typically done in physician offices. Our models suggest potential savings for national health expenditures of around $460 billion over 10 years. That would include some $390 billion in lower commercial insurance premiums and $70 billion in reduced beneficiary cost-sharing. Note that these premium reductions would also increase taxable wages and lower the cost of ACA premium subsidies, leading to further revenue collection that could reduce federal budget deficits by $120 billion.

Option 4: Capping Hospital Prices

Ultimately, high hospital prices are not just an issue for services provided in outpatient departments. Hospitals command average prices in the commercial market that are more than twice as high as Medicare for all services, with over 300 hospitals charging at least three times as much. The pricing power of hospitals represents a market failure driven by many factors including the leverage that branding creates in negotiations with insurers, the limited information available to policyholders on value and quality and, of course, the increasing consolidation that may leave insurers with no realistic options. Research has shown that between 80 and 90 percent of hospital markets in the U.S. are now highly concentrated, up from 65 percent in 1990.

Note, moreover, that consolidation is associated with significant price increases, but no corresponding improvement in quality of care. And those prices are passed along to consumers, employers or the government in the form of higher premiums and out-of-pocket costsharing.

Legislative changes at the federal and/or state level could counteract the growth of hospital market power. At the very least, policymakers should look at altering the payment incentives that drive higher spending, like moving to site neutrality. However, given already high levels of consolidation, more dramatic regulation could be considered.

In a well-functioning market, commercial insurers would negotiate prices reflecting actual cost and perceived quality. Those negotiations would take place against a backdrop of competition among many providers, with no one provider having the ability to substantially influence prices. That doesn’t happen, which is why Health Savers Initiative has looked at the option of limiting commercial prices for hospital services to 200 percent of the Medicare rate.

Medicare sets fees paid to hospitals based on the national average of reported costs, accounting for both operating and capital expenses. Comparing commercial reimbursement rates to Medicare payment rates could thus allow for transparency and administrative feasibility in providing a benchmark for prices across geographic regions.

We estimate that a 200 percent cap would reduce total national health expenditures by just over $1 trillion over 10 years. A bit less than $900 billion would come in the form of reduced insurance premiums, and $100 billion in reduced patient cost-sharing. Note that since hospital charges vary widely today, the cap would only affect 44 percent of hospitals. Limiting the cap just to highly concentrated markets would reduce the captured savings by about 30 percent.

We also expect that, with premiums falling, employers would likely shift a share of worker compensation from non-taxable health care benefits to taxable wages, increasing government revenue. Meanwhile, lower premiums in the Affordable Care Act insurance marketplaces would reduce the cost of government premium subsidies. We estimate these changes would lower federal budget deficits by $220 billion over 10 years.

Option 5: Injecting Price Competition Into Medicare Part B Drugs

The prescription drug sector is another area rife with market failure and misaligned incentives. A good example is the way Medicare Part B (outpatient services) covers the cost of drugs that require delivery in a doctor’s office or in an HOPD: it reimburses physicians the average cost for each specific drug, plus a 6 percent markup. This arrangement thus pays physicians more for prescribing higher priced drugs, blunting competition especially within drug classes that have clinically comparable options but wide variation in prices.

While many conditions for which physician- administered drugs are used have only a single therapeutic option, others are in drug classes that allow choices. Yet Medicare bases payment for each of the interchangeable therapies separately without creating incentives for physicians to select the lowest-cost alternative or for manufacturers to compete on price within these drug classes. This failure increases costs to Medicare. And because Medicare beneficiaries face coinsurance costs of 20 percent (or pay for expensive supplemental insurance), their costs are higher as well.

The 6 percent markup for physicians is a separate fee on top of payment for their professional time administering a drug. It is designed to cover drug storage and handling costs, as well as covering drug costs for physicians unable to get discounts on drug purchases.

Physicians do have some incentive to purchase any given drug at the lowest available price because reimbursements are fixed at 106 percent of the average price, making it profitable to obtain the drug at a lower price. However, they still have an incentive to choose more expensive drugs if they can obtain those drugs with a similar discount. And the differences can be dramatic, with 10-fold differences between the least and most expensive therapy choices.

The Health Savers Initiative looked at implementing “clinically comparable drug pricing,” where Medicare payments for physician- administered drugs would be set at a single price for groups of drugs within the same therapeutic class. That price would be set at the weighted average of prices manufacturers charge for each of the clinically comparable drugs.

Insured patients would face standard cost sharing for the weighted average and could not be billed by providers for drug costs above that price. Beneficiary cost-sharing would also be based on the lower of the weighted average for the group or the average price for the specific drug used. This would not only prevent beneficiaries already on the lowest-cost drug from having their cost-sharing burden increase but would also strengthen the incentive to select a lower-cost option.

Note the potent change in incentives for providers. They would absorb all the extra costs associated with choosing a drug priced above the weighted average and would receive all the savings for choosing a drug priced below the weighted average.

In order to estimate the fiscal and financial impact of moving to clinically comparable drug pricing, we analyzed three important therapeutic classes: drugs to treat macular degeneration, rheumatoid arthritis and prostate cancer.

The wide discrepancies in prices among comparable therapies in these classes dramatically highlights the missed opportunity of not leveraging competition to obtain savings. For example, the annual per-beneficiary cost for treatment of “wet” age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with the drug Eylea exceeds $9,000, while treatment with Lucentis exceeds $8,000. By contrast, the annual cost for treatment with Avastin, an effective treatment originally developed for cancer, is as little as $300.

The price differential among treatments for rheumatoid arthritis is also substantial, if less theatrical. Treatment with Orencia and Rituxan exceed $27,000 and $38,000 annually, respectively, while treatment with the biologic drug Remicade and its biosimilars Inflectra and Renflexis costs between $10,000 and $11,000.

The third class of therapeutics, for prostate cancer, presents somewhat less dramatic differences. Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that Zoladex and Trelstar cost double what Eligard costs without offering superior outcomes.

From these three drug classes alone, we estimate that changed pricing incentives would save Medicare more than $120 billion over a decade. Furthermore, since it could (and should) be applied to other classes of drugs, too, savings from a broader implementation of this policy could be considerably higher.

Because Medicare’s price is derived from prices paid by all purchasers, the new policy would influence the commercial market as well. Manufacturers of drugs for which Medicare represents a significant market share may find it challenging to maintain higher commercial prices in the face of this new, lower Medicare payment.

We looked at an example of such commercial savings using the rheumatoid arthritis drugs, since commercially insured patients do use a substantial share of all relevant drugs. A rough estimate of the savings, assuming half the rate of savings possible for Medicare, is $20 billion dollars over 10 years.

Note that the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) enacted in August of 2022 gave Medicare authority to negotiate drug prices. The negotiations are limited to drugs lacking generic competition and apply to 15 drugs, including those in Part B, beginning in 2028 and 20 drugs in 2029 and beyond. Starting this year, drug price increases for Medicare are limited to the general rate of inflation.

Our analysis pre-dates enactment of the IRA. If Medicare negotiation is implemented in full, it is likely that the savings from changing Part B payment policy will be a bit lower since Part B spending is highly concentrated among just a few products, and those could become a target for negotiation. Still, changing the misaligned incentives that lead physicians to prescribe higher cost drugs would remain important, as there are no limits on high initial launch prices and only a small number of Part B drugs would be eligible for negotiation within the estimated budget window.

Option 6: Limiting Evergreening for Name-Brand Prescription Drugs

Drug manufacturers are often able to take advantage of FDA rules designed to encourage innovation that prohibit generic drug competitors’ access to the market for a long period. One drug company strategy called “evergreening” games the FDA rules to extend market exclusivity periods by either delaying generic drug market entry or by limiting the number of patients who have access to a generic version when it does come on the market.

Classic evergreening involves introducing a new “line,” or version of a drug shortly before the generic competitor is slated to be available. For example, a manufacturer may introduce an extended-release formulation as an alternative to the generic immediate-release formulation about to hit the market. The idea is to hold market share for the expensive branded drug in spite of generic competition, thereby increasing insurer and patient costs.

The Health Savers Initiative looked at how changes to FDA exclusivity rules could lead to meaningful savings. One proposed change would allow generics makers to launch their own extended-release products sooner, cutting the branded versions’ period of extended release exclusivity. The FDA would deny approval to an application for an evergreened product in the three years prior to expected generic competition, which is normally triggered by patent expiration. The new rules could also speed up the market entry of branded extended- release products and other reformulations, providing clinical benefits to patients.

Over a decade, we estimate this narrowing of the evergreening window would reduce federal outlays by roughly $10 billion over 10 years. There would also be savings in the commercial prescription drug market. Total savings (including out-of-pocket spending) would be about $20 billion.

In the initial 10-year period, savings would be derived largely by earlier launches of extended- release products and their substitution for existing immediate-release products. In subsequent periods, savings would arise from extended-release products launching concurrently or within three years of new immediaterelease products. To be sure, the negotiation flexibility given to Medicare under the IRA would likely reduce some of these savings, but the clinical benefits of earlier access to improved formulations would remain.

* * *

These six options are hardly the only ways to reduce health care spending without reducing quality. But they would be major steps forward in addressing the market failures and misaligned incentives that drive high spending. They would also be tests of Washington’s determination to increase the efficiency of the health care system in the face of powerful lobbying for the status quo on the part of entrenched interests.

If we can’t begin to move toward lower costs as the Medicare trust fund faces impending insolvency, it is hard to imagine that we will ever be able to manage the more difficult task of making sure that everyone has access to adequate health care while saving the nation from economic stagnation due to the burden of our unsustainable fiscal path.

Josh Gordon is the director of health policy for the Committee for a Responsible Budget and runs our Health Savers Initiative. Darbin Wofford is a former senior health associate.