What the New GDP Numbers Mean for Budget Projections

Yesterday, we noted the revisions that CBO has made to its historical budget data going back to 1973, in light of the Bureau of Economic Analysis's revisions to GDP numbers going back to 1929. Although the nominal dollar totals are unaffected, numbers that were estimated as a percentage of GDP have all been revised downward, as a result of the higher GDP. We pointed out that the revisions were noticeable but certainly not huge.

But even if the revisions to past data were not course-altering, budget wonks and lawmakers will be watching closely to see how budget projections will change as a result. In this post, we use the CRFB Realistic baseline to show how budget projections might change, with the caveat that these are, of course, not official numbers and may not fully represent the changes that would be made to either budget or economic projections as a result of the GDP revisions. In particular, we have used the new GDP levels but assume the same growth rates CBO has in its projections.

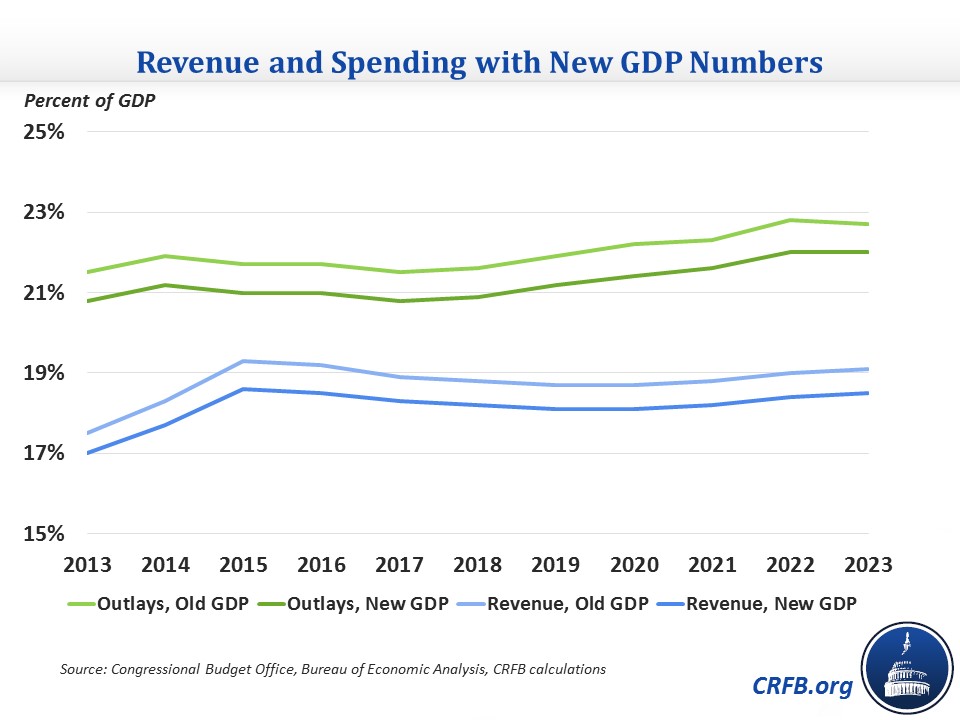

First, there is spending and revenue, which have been revised down compared to the old GDP numbers by about half a percentage point each year. Spending and revenue in 2023 equal 22 percent of GDP and 18.5 percent, respectively, whereas they had previously been 22.7 percent and 19.1 percent. The ten-year average of spending and revenue is revised down from 22.1 percent and 18.9 percent, respectively, to 21.3 and 18.3 percent.

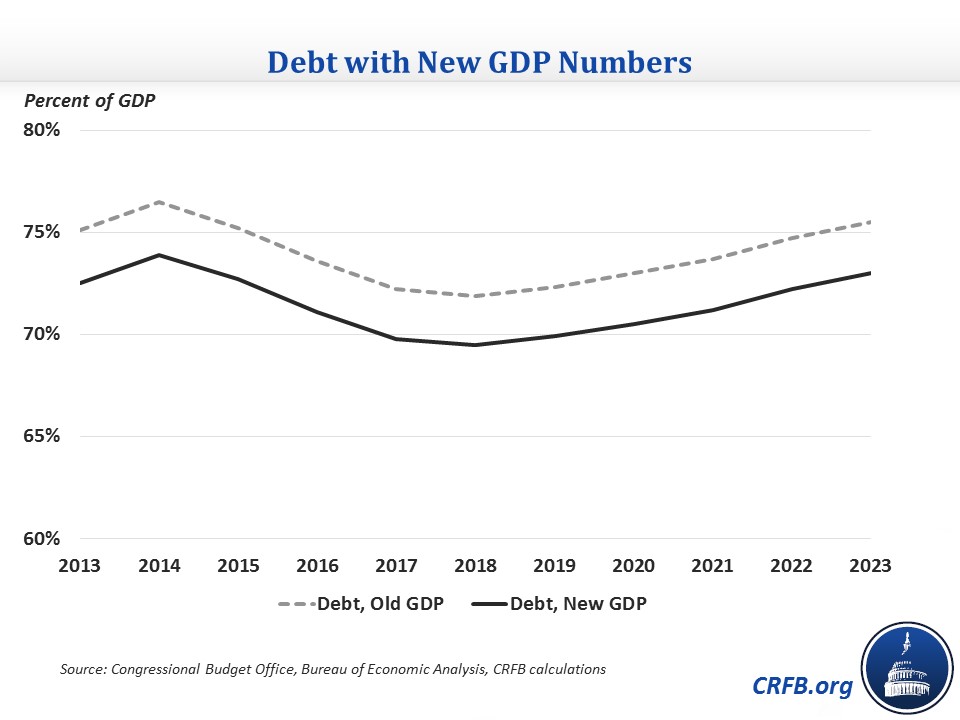

The new GDP numbers lower yearly deficits as a share of GDP by about one-tenth of one percentage point annually, only a small difference. For debt, the new GDP levels lower debt-to-GDP by about 2.5 percentage points annually. Under current Realistic projections, debt will rise to 76.5 percent of GDP in 2014, fall to a low of 71.9 percent in 2018, and then rise to 75.5 percent by 2023. After incorporating the new numbers, debt would rise to 74 percent by 2014, fall to a low of 69.5 percent by 2018, and then rise to 73 percent by 2023. Note that while the levels of debt have fallen, the trajectory is very similar.

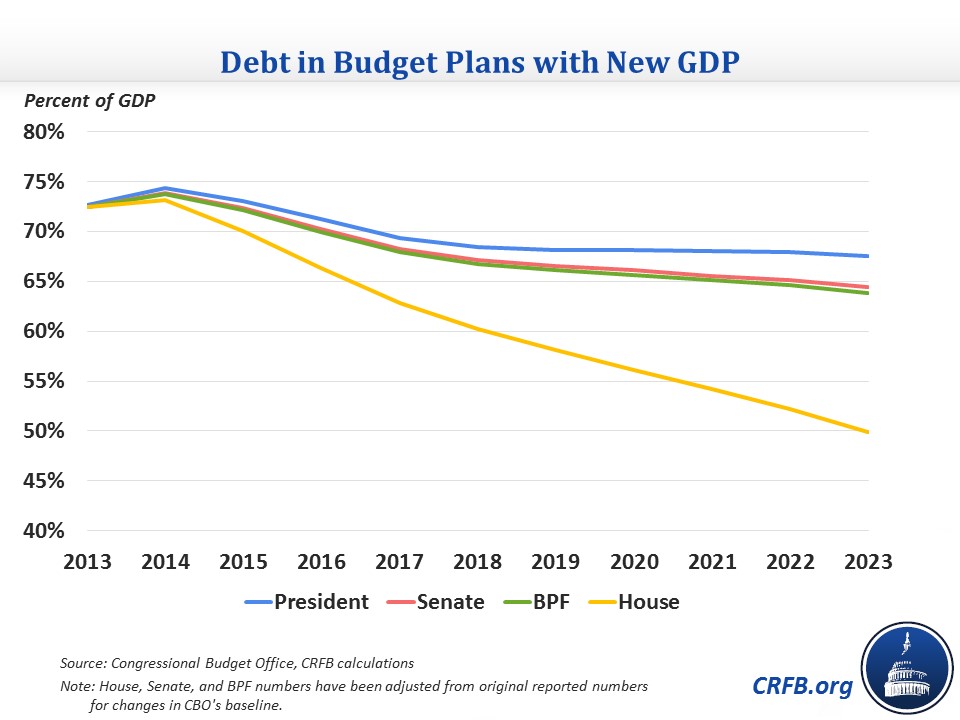

In addition, we have used the new GDP numbers to re-estimate debt-to-GDP in the budget plans from the President, the House, the Senate, and the Bipartisan Path Forward. Again, the debt trajectories remain the same, but the level of debt in 2023 is about 2 to 3 percentage points lower than previously estimated. 2023 debt in the House and Senate budgets (adjusted for changes in CBO's May baseline) are revised down from 52 percent and 67 percent, respectively, to 64.4 percent and 50 percent. Debt in the President's budget in 2023 is revised down from 69.8 percent to 67.5 percent. And 2023 debt in the Bipartisan Path Forward is revised down from 66.2 percent to 63.8 percent.

Importantly, all of these re-estimates assume that projected GDP growth rates stay the same. However, BEA's revisions also bumped up the average GDP growth rate from 1929-2012 by 0.1 percentage points annually. If we assume that would hold true going forward, it would further lower numbers calculated as a percent of GDP, although not by as much as the changes in GDP levels. Incorporating the new growth would have spending and revenue in 2023 at 21.7 percent of GDP and 18.3 percent, respectively, while debt would be 72.2 percent of GDP in that year.

Ultimately, we will see how much has changed when CBO releases its long-term outlook in September. At that time, it will likely incorporate the new GDP numbers but will not change its ten-year budget projections (although its projections beyond 2023 will change). Based on what we have calculated, the GDP revisions will change the level of the budget metrics but not the trajectory, which we consider to be the most important.