We Need To Improve Focus on the Long Term

Today CRFB released a new paper as part of our Better Budget Process Initiative titled "Improving Focus on the Long Term."

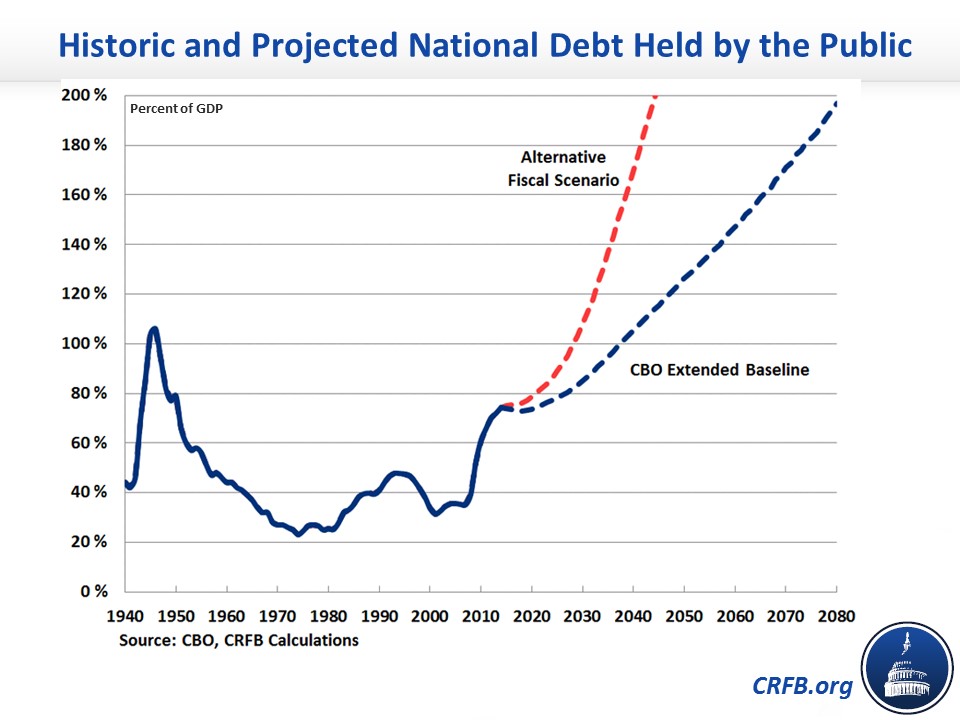

The budget process focuses on the short term, often at the expense of longer-term considerations (like how our long-term debt problem is far from being solved). This distortion allows policies to be crafted in ways that mask their true costs and contributes to results that downplay looming fiscal challenges.

The short-term focus contributes to many poor outcomes, such as emphasis on short-term deficit reduction (with little improvement in the long-term fiscal outlook), the use of “timing gimmicks” designed to obscure the budgetary impact of policy choices, and the reliance on one-time savings to ensure “deficit-neutrality” within the budget window but deficit increases beyond it. It also often causes policymakers to undervalue policies which achieve modest savings over the ten-year window but much greater savings after that to help "bend the debt curve" over the long term. (For more on looking beyond the ten-year window, see our prior paper on the subject)

In addition, the short-term focus has made it conducive for many in Washington to brag that the fiscal situation is under control based on a short-term improvement in the deficit, despite the fact that the debt is projected to grow faster than the economy for the medium and long term.

The short-term emphasis is the result of both an overreliance the ten-year budget window for scoring and analysis and insufficient enforcement of long-term fiscal goals.

In the paper, we provide background on the current process, highlighting where policymakers focus on the short term and the limited cases where the long term is emphasized. In the paper's appendices we provide an in-depth discussion of important considerations for long-term budget estimates, methodologies available for long-term analysis, and a history of long-term budgetary analysis.

Our paper addresses 6 possible options for changes to the rules governing the budget process to help policymakers focus on the long term:

1. Require long-term estimates for certain legislation

Focusing exclusively on the short- and medium-term estimates of budgetary effects of legislation can encourage the implementation of policies that result in rising long-term debt. These can involve pairing short-term savings with long-term spending or tax cut policies and discounting policies which achieve significant long-term savings but have little or no ten-year savings. Congress should require the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to provide estimates of budgetary effects beyond the first decade for legislation with significant fiscal impact.

2. Codify rules prohibiting legislation increasing long-term deficits

A current Senate point of order against increasing the long-term deficit was established by a budget resolution, but it does not have the force of law. As a result, it can easily be changed, weakened, or repealed by another budget resolution. There is no comparable point of order in the House of Representatives. The point of order prohibiting significant increases in the long-term deficit should be codified in its current form in the Budget Act and applied to both chambers of Congress.

3. Allow long-term savings targets for reconciliation

Reconciliation instructions require committees to achieve savings over the budget window covered by the budget resolution, usually ten years. While a powerful tool, reconciliation has limited capacity to encourage policymakers to address the country’s largest fiscal challenges, which are over the long run. Committees have an incentive to meet savings targets through one-time savings or policies with large upfront savings that do not grow over time. The Budget Act should be amended to allow budget resolutions to set aggregate deficit reduction goals for the second ten-year window and include reconciliation instructions with a second decade deficit reduction target to encourage policymakers to meet reconciliation targets with sufficiently backloaded policies.

4. Establish a second-five-year test for PAYGO

Statutory PAYGO and the current PAYGO rule in the Senate require legislation to be offset over only the first five- and ten-year period. But this allows many bills to frontload savings and result in increases in the deficit in later years of the ten-year budget window that are likely to continue beyond then. Requiring legislation to be deficit-neutral over both the first five years and second five years would apply discipline to legislation that has early savings and later costs that are likely to lead to increased deficits beyond the ten-year window.

5. Require annual budget documents to include long-term information

Currently, the president’s budget includes a long-term outlook in its Analytical Perspectives volume, and CBO prepares a separate report on the long-term outlook. Long-term estimates are not included in the summary budget tables or presentations in the President’s budget; CBO's long-term projections are not included in its annual budget and economic outlook in January and its midyear assessment of the budget; and a Congressional budget resolution is not required to include any information regarding long-term fiscal impact. Congress should require that these annual budget documents include more focus on the long term.

6. Expand the use of accrual accounting where appropriate

For the most part, the federal budget uses a cash-based approach in measuring program costs. A cash-based approach is inadequate for giving federal policymakers information about the long-term financial costs of long-term commitments. An accrual approach, which records the net present value of these commitments in the year they are made, regardless of the actual flow of cash payments, could more accurately reflect future federal obligations in some instances.

While none of these changes will solve our long term fiscal challenges by themselves, reforms which provide an increased focus on the long-term fiscal impact of legislation and make it harder to pass legislation which would worsen the long-term outlook could be useful tools to help improve the long-term fiscal outlook. For an in-depth discussion of the value of focusing on the long term see the full paper. Also take a look at the first paper of the Better Budget Process Institute "The Budget Act at 40: Time for a Tune Up?"