The Tax Break-Down: Municipal Bonds

This is the sixth post in a new CRFB blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which will analyze and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform. Last week, we profiled the Section 199 manufacturing incentive, one of the largest corporate tax breaks.

Interest earned from state and local government bonds has been tax-free since the income tax started in 1913. The interest that people earn from holding these bonds, unlike other interest, does not count as income. In this case, the federal government forgoes income tax revenue to indirectly subsidize the cost of borrowing for local governments.

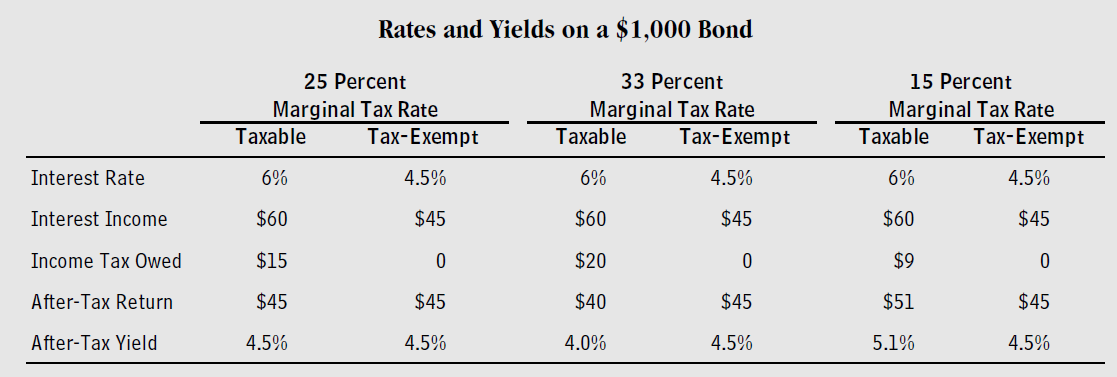

Because these municipal bonds offer tax-free return, investors are willing to accept a lower level of interest, depending on their individual tax rates. For instance, an investor in the 25 percent tax bracket who earns 6 percent interest on a taxable bond will pay a quarter of that interest in taxes (1.5 percentage points). The investor would receive the same after-tax return from a municipal bond providing 4.5 percent in tax-free interest. An investor in a higher tax bracket would see a larger benefit and so would prefer a 4.5 percent municipal bond to a 6 percent taxable bond. Investors in lower tax brackets would prefer the taxable bond.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Since investors accept a lower rate of return than would otherwise be the case, the tax exemption lowers the cost of borrowing for state and local governments, who issue bonds to support transportation, education, health, utilities, and many other capital projects. This category of tax-exempt bonds comprises a substantial municipal bond market, with over $3.7 trillion in outstanding bonds and $11.3 billion traded daily in 2012.

Prior to 1960, state and local governments could essentially engage in unlimited tax-preference borrowing on behalf of themselves or private businesses. Restrictions enacted over the last 30 years have restricted but not eliminated the issuance of tax-exempt "private activity bonds." For taxpayers paying the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), no private activity bond interest is exempt from taxes.

How Much Does It Cost?

The exclusion of interest income on municipal and private activity bonds will cost the federal government $58 billion in 2013 and approximately $540 billion over the next ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). Of that total, traditional governmental bonds cost $420 billion and private activity bonds cost another $120 billion. Approximately $130 billion goes to corporate bondholders, and the other $410 billion goes to taxpayers paying the individual income tax.

The tax treatment of municipal bonds is a small but significant portion of federal aid to states. The largest segment of federal aid is grants given directly to the states, which totaled $560 billion in FY 2013. Next is the state and local tax deduction, costing $77 billion. Third is the tax break for municipal bonds, costing $34 billion this year.

Assuming full repeal of the tax exemption would raise approximately $500 billion over ten years, doing so would finance a 4.5 percent across-the-board cut in tax rates (the 39.6 percent rate would drop to 37.8 percent, for example), based on Tax Foundation estimates from repealing other provisions with similar costs.

Who Does It Affect?

Tax-free income on municipal bonds has both direct and indirect beneficiaries. The direct beneficiaries are the investors – bond holders who receive tax-free interest. Three-quarters of municipal bonds are held by individuals, either directly or indirectly through mutual funds. Measured by the direct effects, the benefits are skewed to those at the top of the income spectrum. One analysis from the Tax Policy Center found that, under a hypothetical tax plan with a top marginal rate of 28 percent, 85 percent of the benefit of this provision would go to taxpayers making over $200,000. Current law has a top tax rate more than 10 points higher, so taxpayers at the top likely benefit even more.

Importantly, though, looking only at the direct benefit of the preference misses a key benefit of the tax break – to provide the states and localities with cheaper borrowing costs.

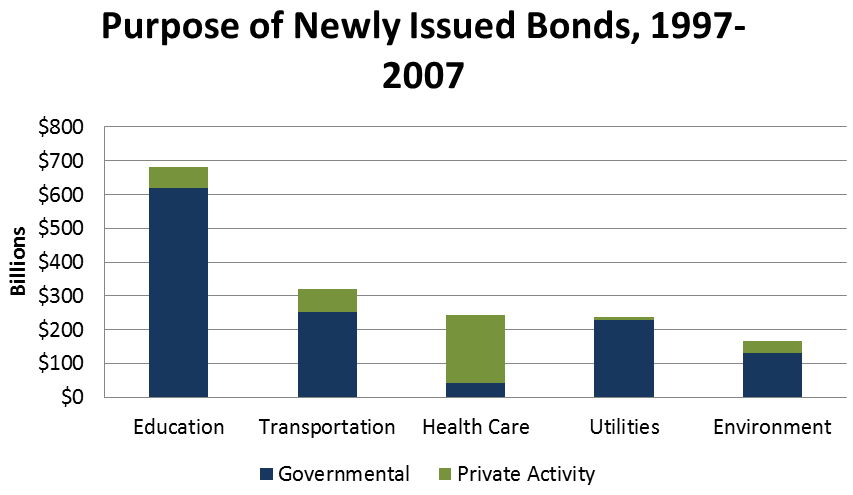

The largest share of municipal bonds goes to fund public and nonprofit education projects, which totaled almost $700 billion from 1997 to 2007. Transportation projects are the next largest segment, making up one-fifth of the total. Health care bonds make up 15 percent, mostly in the form of private activity bonds.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

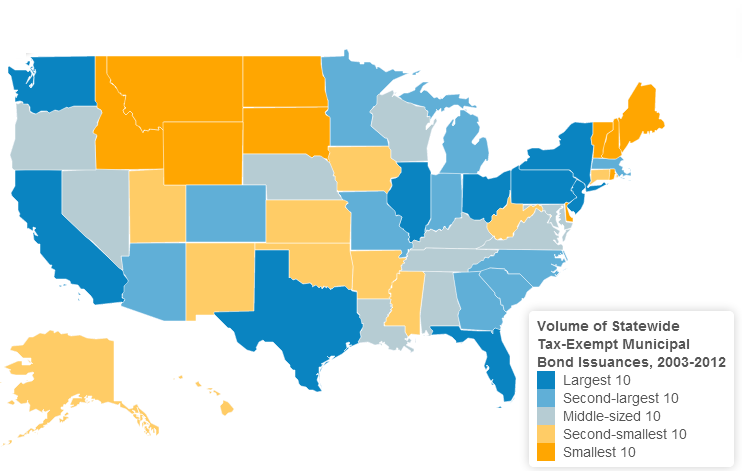

Those states and localities that rely more heavily on bond financing receive more of the benefit. Heavily-populated states like California, Texas, New York, and Florida disproportionately benefit.

Source: National Association of Counties

What are the Arguments For and Against Excluding the Interest on Municipal Bonds?

Proponents of the municipal bond tax exemption argue that the exclusion provides important support for state and local governments to invest in infrastructure, education, health care, and other productive public investments. They also point out that infrastructure investment in the United States is centered around the tax-exemption, with a $3.7 trillion bond market. Changes to the exclusion – especially for existing bonds – could cause severe disruptions in this large market and thus the broader economy. Reduction could also hurt the ability of state and local government to borrow, as evidenced by S&P’s warning that reducing the tax benefits around municipal bond interest would have "negative credit implications for state and local governments and other tax-exempt issuers."

Opponents of the exclusion argue that the tax code should not be the vehicle for supporting local governments and local projects, especially those that are private purpose and benefit a small group of people, like a sports stadium. To the extent these projects are worthy, opponents argue that a tax exemption is an expensive and poorly targeted way to encourage investment, often citing a report by CBO that one-fifth of the subsidy has no impact on interest rates and is simply a windfall to investors in higher tax-brackets. Finally, the tax-exemption for municipal bond interest provides a huge benefit for some who want to minimize or possibly eliminate their tax burden. Along with charitable giving, municipal bonds are a major reason that some rich people have a very low or sometimes zero tax bill. Over 16,000 taxpayers with an income over $200,000 do not pay any taxes; tax-free bonds are the reason for three-fifths of them, according to the IRS.1

What are the Options for Reform?

On a static basis, repealing the interest exclusion for tax-exempt bonds would raise about $500 billion over a decade, or $200 billion if applied only to newly-issued bonds. As with most large tax expenditures, however, a number of options exist to trim or reform the tax break without completely repealing it. Any reform option could be applied to all municipal bonds, changing the tax treatment of investments that have already taken place, or phase-in the change with only newly issued bonds.

As one example, Congress could repeal certain elements of the tax-exemption – such as disallowing private activity bonds or repealing the exclusion for corporations (who can also borrow tax free). Policymakers could also pursue a haircut approach like limiting the value of the exclusion to that provided by the 28 percent tax bracket.

Another often-discussed option would be to eliminate the exclusion and in place offer a credit. That credit could be set at a specific level or adjustable to achieve a certain interest rate, it could itself be taxable or not, and it could go to the owner of the bond or directly to the issuer. This credit would not only be more progressive than the current system, but it would be more efficient since much of the “windfall” associated with the current system comes from the fact the current system provides a higher effective subsidy to those in the top tax brackets. According to the CBO, this change can offer the equivalent investment subsidy at a lower cost to the government (or a higher subsidy at the same cost).

| Revenue from Reform Options for Municipal Bonds (2014-2023) | |||||

| Policy | Apply to New Bonds | Apply to All Bonds | |||

| Eliminate exclusion for all municipal bonds | $200 billion*F | $500 billionS | |||

| Eliminate exclusion for private activity bonds, only | $30 billion | $100 billionS | |||

| Eliminate corporate exclusion for all bonds | $50 billionF | $120 billionS | |||

| Eliminate corporate exclusion for private activity bonds, only | $10 billion | $25 billionS | |||

| Cap income exclusion at 28% | $20 billionF | $50 billion | |||

| Replace Exclusion with a 25% Credit | $25 billion | $60 billionF | |||

| Replace with 15% Credit | $150 billion | $375 billionF | |||

| Eliminate private activity bonds for non-profit hospitals | $10 billionF | $25 billionS | |||

| Eliminate advanced refunding of bonds to eliminate “double subsidy” | $10 billion | unknown | |||

| Limit issues to $100 million of tax-exempt debt annually | $50 - $85 billion† |

n/a |

|||

* - JCT recently estimated that repealing the tax-exemption for newly-issued bonds would raise $124 billion; However, it is not clear if this score includes private activity bonds or interest received by corporations.

S - Static estimate based on tax expenditure value

F - Based on assumption that grandfathering existing bonds will result in savings 40 percent as large as applying to all bonds.

† - Estimate provided by Breckinridge Capital Advisors, Inc., at the author's request.

What Have Tax Reform Plans Done With Municipal Bonds?

Most major tax-reform plans would retain some form of tax preference for municipal bonds, though at a lower cost than the current preference. The Wyden-Gregg/Coats legislation would replace the exclusion with a 25 percent credit for new issuers, for example. The Center for American Progress would limit municipal bonds with a per-state cap similar to private activity bonds and fully reinstate Build America Bonds, a type of tax credit bond that was enacted in the 2009 stimulus on a temporary basis. The 2005 tax reform panel kept the exclusion for individuals, but eliminated the exemption for businesses “because of the flexibility businesses have to deduct interest.” The Domenici-Rivlin plan, meanwhile, retained the exclusion for public purpose bonds but eliminated it for private activity bonds.

Only the Fiscal Commission would repeal the tax-exemption entirely, and even they would do so only for newly issued bonds and would phase out the exemption for those new bonds gradually rather than immediately.

Where Can I Read More?

- Congressional Budget Office/Joint Committee on Taxation – Subsidizing Infrastructure Investment with Tax-Preferred Bonds

- Congressional Budget Office – Testimony on Federal Support for State and Local Governments Through the Tax Code

- National Association of Counties – Municipal Bonds Build America: A County Perspective on Changing the Tax-Exempt Status of Municipal Bond Interest

- Calvin Johnson – Repeal Tax Exemption for Municipal Bonds

- Center for American Progress – Bring Back BABs: A Proposal to Strengthen the American Bond Market with Build America Bonds

- Tax Policy Center – Tax-exempt bonds

- Joint Committee on Taxation – Present Law and Background Information Related to Federal Taxation and State and Local Government Finance

*****

The exclusion for interest on state and local bonds is an expensive tax preference that steers investors toward a category of investments that may not otherwise be preferable to unsubsidized investments. On the other hand, states and investors have come to rely on tax-free municipal bonds as the main way to finance infrastructure. Importantly, whatever the merits of having the exclusion in the first place, there is a $3.7 trillion market built around the exclusion. Reforms must be careful and deliberative, particularly in how they treat previously-issued debt. Still, tax reform offers an opportunity to make the way we subsidize public investments far more efficient, or carefully unwind subsidies if they are determined to be undesirable. In the process, these reforms could generate new revenue for rate reduction, deficit reduction, or both.

Read other pieces in the Tax Break-Down here.

1As described by former Representative (and CRFB board member) Bill Frenzel, the main impetus for enacting the AMT was to ensure that high earners whose income relied mainly on municipal bonds paid at least some tax. However, Congress ultimately decided to enact the AMT without taxing bonds.

Note: This post has been updated on September 13, 2013 to include an additional revenue estimate from Breckinridge Capital Partners that was not available at the time of publication.