State & Local Aid is On Its Way, But Is It Needed?

Last week, the Department of Treasury issued guidelines for the allocations of $350 billion of direct state and local aid funds in the American Rescue Plan (ARP). We estimate roughly $235 billion will be issued this year, and $115 billion in a second tranche next year.1

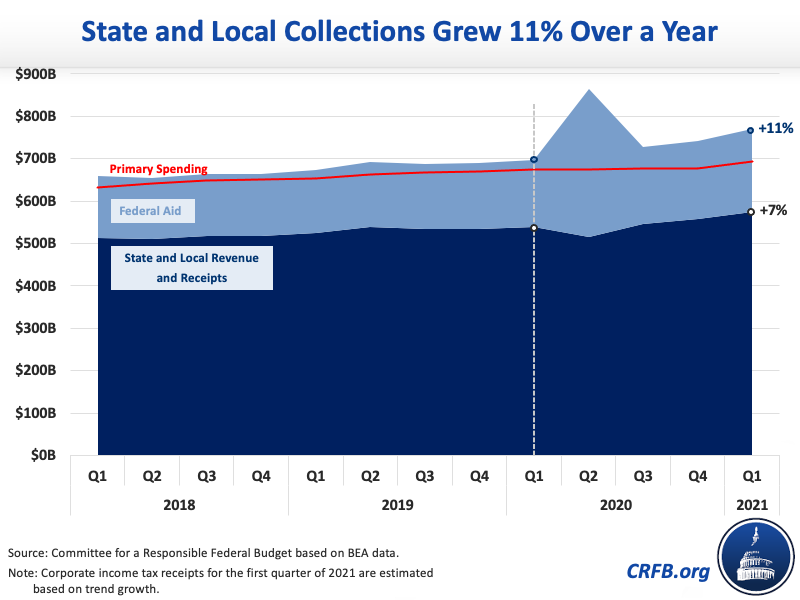

In total, Congress has allocated around $900 billion to state and local governments and entities through various COVID relief bills. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), total state and local revenue last quarter was roughly 7 percent above pre-pandemic levels before accounting for federal aid and 11 percent higher inclusive of federal aid. Declines in COVID cases, economic recovery, and additional aid is likely to lift state and local revenue collections even further.

Treasury Guidance on State and Local Aid

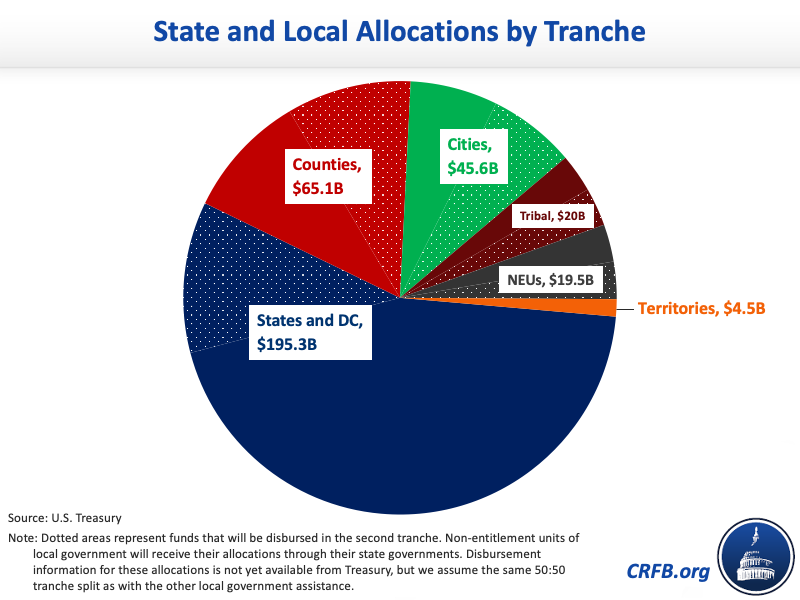

The American Rescue Plan included roughly $525 billion of state and local aid, including $350 billion of direct aid through the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (CSLFRF) (remaining aid would go mainly to public schools). The $350 billion includes about $195 billion for states and the District of Columbia, $130 billion for local governments (including $65 billion for counties, $46 billion for cities, and $20 billion for smaller towns), $20 billion for tribal governments and $5 billion for U.S. territories.

Local governments will receive 50 percent of their assistance — or $65 billion — this month and will receive the remainder in a second tranche a year from now. State governments in states with less than a two-percentage-point increase in their unemployment rate from February 2020 will similarly get their money in two tranches, though those with unemployment rates two-percentage-points larger will get their funds all at once. Based on state unemployment data as of May 10, 20 states and the District of Columbia will get their money upfront and 30 states will get their money in two tranches. If these estimates hold, $156 billion of state money will be disbursed upfront and $39 billion will be disbursed a year from now.

As Treasury explained, recipient governments can use funds for public health measures; economic relief for businesses and individuals; hazard (or premium pay) to essential workers; to invest in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure; and to replace revenue lost as a result of the pandemic. “Lost revenue” will be calculated based on the difference between actual revenue and an alternative representing counterfactual trend growth in revenue absent the pandemic.2

States may not use funding to offset net tax cuts from March 3, 2021; top up pension funds, rainy day funds, or reserves; fund debt service; pay legal settlements or judgments; or for general infrastructure spending (other than water, sewer, and broadband). States will still be able to implement tax cuts in the ARP years (March 2021 through December 2024) if they are offset with other tax increases, spending cuts, or if their annual revenue is in excess of (or less than one percent below) their 2019 baseline revenue — Treasury will consider that these tax cuts were paid for with economic growth rather than from the relief funds. Treasury will consider tax cuts that reduce revenues to more than one percent below baseline 2019 levels to be a violation of the terms of the assistance and may try to claw back funding.

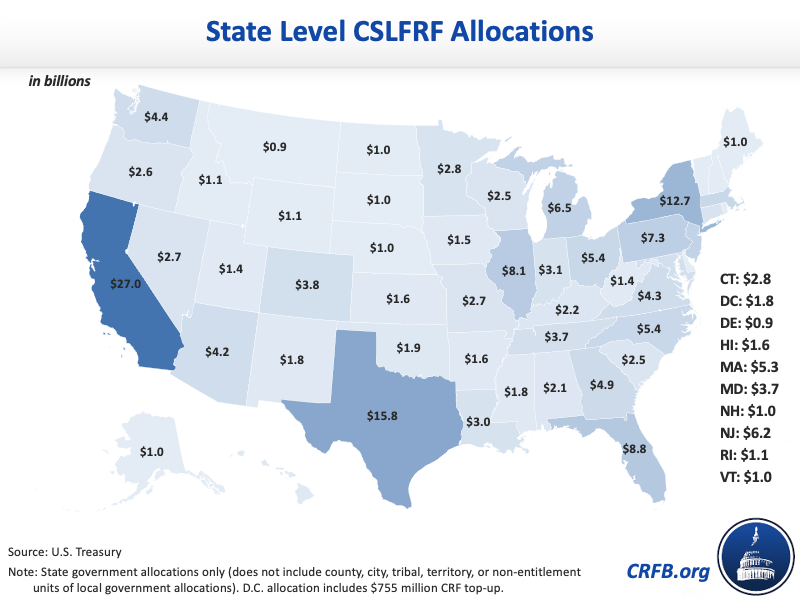

Of the $195 billion in direct aid to state governments, each state and the District of Columbia receives an equal apportionment of funding — $500 million, whereas the rest of the funding is allocated based on the proportional average number of seasonally-adjusted unemployed persons in the state (or District of Columbia) over the three-month period through December 2020. Subsequently, California, Texas, and New York will receive the largest allocations — $27 billion, $15.8 billion, and $12.7 billion, respectively. In contrast, South Dakota, Delaware, and Montana will receive the smallest allocations — $975 million, $925 million, and $906 million, respectively.

Through the American Rescue Plan, states are also set to receive $123 billion in public school funding, $31 billion in aid to transit authorities, and $21 billion in other assistance, including further increases in the federal share of Medicaid payments, discretionary funds for governors to spend on educational services, and additional need-based funding for counties and tribal governments. Inclusive of these funds, California governments will receive at least $63 billion and Montana state and local recipients will receive a little over $1.6 billion.

Inclusive of previous COVID-relief legislation, we estimate total state and local aid will total at least $884 billion – including $500 billion of direct aid, $201 billion to schools, $101 billion through a higher Medicaid matching rate, $70 billion for transit, and $13 billion for everything else. You can explore this data by state at COVIDMoneyTracker.org. So far, at least $425 billion has been committed or disbursed.

As we’ve explained before, this does not include indirect aid to state and local governments (for example, through taxable unemployment benefits or stronger economic growth), support for loans, and funding where state and local governments act primarily as a pass-through. All told, state and local governments are likely to be well over $1 trillion better off as a result of COVID relief legislation.

Do States Need the Money?

The same day as the allocations of $350 billion in state and local aid was announced, California Governor Gavin Newsom revealed the state – which is slated to receive $27 billion of direct state aid and roughly $50 billion of combined aid (including school, transit, Medicaid, etc.) – is projecting an enormous $75.7 billion budget surplus across two fiscal years. Other states, including New Jersey, Arizona, Texas, and Idaho have also recently announced surpluses.

In fact, a recent Urban Institute analysis estimates that total state tax revenue (excluding federal aid) in March was 10.8 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels. Based on BEA data, total state and local tax collections were 11 percent above pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter; even excluding federal aid, state tax collections were 7 percent above pre-pandemic levels. By comparison, inflation and nominal GDP growth were both less than 2.5 percent over the same period.

Over the course of the pandemic, total state and local receipts were 12 percent higher than the year earlier (though due to a dip in the second quarter of 2020, tax revenue was only 2 percent higher excluding federal aid).

We highlighted back in February that the proposed state and local ARP aid was likely excessive given better than expected state and local finances in the aggregate. State and local governments fared better than originally forecast thanks to a brighter economic outlook and substantial direct and indirect federal aid.

New data appears to confirm this, at least in the aggregate. Further funding from the American Rescue Plan is likely to push state and local receipts to record levels in the second quarter of 2021. While some states — for example, tourism-dependent states like Hawaii — may need these funds, for many it will represent a substantial windfall.

To ensure these dollars are spent well, policymakers at the state, local, or federal level could consider purposing or repurposing some of them to cover new long-term infrastructure investments such as those proposed in the President’s $2.65 trillion American Jobs Plan.

State and local governments must avoid using these temporary funds to support permanent policy changes that lead to larger future imbalances.

Appendix

The allocations for state and local governments, tribes, territories, and non-entitlement units of local government are below. The $20 billion in tribal government allocations are not yet available by state.

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund Allocations by State, in millions of dollars

| Entity | State/Territory/Tribe | County | City | Non-Entitlement | Grand Total | Estimated Upfront Payment* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alabama |

$2,120 |

$952 |

$431 |

$356 |

$3,860 |

$1,930 |

|

Alaska |

$1,012 |

$142 |

$53 |

$43 |

$1,250 |

$625 |

|

Arizona |

$4,183 |

$1,414 |

$1,003 |

$227 |

$6,827 |

$3,413 |

|

Arkansas |

$1,573 |

$586 |

$209 |

$216 |

$2,584 |

$1,292 |

|

California |

$27,017 |

$7,675 |

$7,005 |

$1,218 |

$42,915 |

$34,966 |

|

Colorado |

$3,829 |

$1,119 |

$551 |

$265 |

$5,764 |

$4,796 |

|

Connecticut |

$2,812 |

$693 |

$661 |

$203 |

$4,369 |

$3,591 |

|

Delaware |

$925 |

$189 |

$64 |

$91 |

$1,268 |

$1,096 |

|

District of Columbia |

$1,802 |

$137 |

$373 |

$0 |

$2,312 |

$2,057 |

|

Florida |

$8,817 |

$4,172 |

$1,518 |

$1,416 |

$15,923 |

$7,961 |

|

Georgia |

$4,854 |

$2,072 |

$576 |

$862 |

$8,364 |

$4,182 |

|

Hawaii |

$1,642 |

$275 |

$197 |

$46 |

$2,160 |

$1,901 |

|

Idaho |

$1,094 |

$347 |

$124 |

$108 |

$1,673 |

$836 |

|

Illinois |

$8,128 |

$2,461 |

$2,726 |

$742 |

$14,058 |

$11,093 |

|

Indiana |

$3,072 |

$1,308 |

$848 |

$433 |

$5,660 |

$2,830 |

|

Iowa |

$1,481 |

$613 |

$339 |

$222 |

$2,654 |

$1,327 |

|

Kansas |

$1,584 |

$566 |

$260 |

$167 |

$2,577 |

$1,289 |

|

Kentucky |

$2,183 |

$868 |

$395 |

$324 |

$3,771 |

$1,885 |

|

Louisiana |

$3,011 |

$903 |

$589 |

$315 |

$4,819 |

$3,915 |

|

Maine |

$997 |

$261 |

$122 |

$119 |

$1,499 |

$750 |

|

Maryland |

$3,717 |

$1,174 |

$619 |

$529 |

$6,040 |

$4,878 |

|

Massachusetts |

$5,286 |

$1,339 |

$1,665 |

$385 |

$8,674 |

$6,980 |

|

Michigan |

$6,540 |

$1,940 |

$1,823 |

$644 |

$10,947 |

$5,474 |

|

Minnesota |

$2,833 |

$1,111 |

$644 |

$377 |

$4,966 |

$2,483 |

|

Mississippi |

$1,806 |

$578 |

$101 |

$268 |

$2,754 |

$1,377 |

|

Missouri |

$2,685 |

$1,192 |

$831 |

$450 |

$5,158 |

$2,579 |

|

Montana |

$906 |

$208 |

$50 |

$86 |

$1,250 |

$625 |

|

Nebraska |

$1,040 |

$376 |

$176 |

$111 |

$1,703 |

$852 |

|

Nevada |

$2,739 |

$598 |

$292 |

$151 |

$3,780 |

$3,259 |

|

New Hampshire |

$995 |

$264 |

$86 |

$112 |

$1,457 |

$728 |

|

New Jersey |

$6,245 |

$1,828 |

$1,190 |

$578 |

$9,840 |

$8,042 |

|

New Mexico |

$1,752 |

$407 |

$171 |

$126 |

$2,456 |

$2,104 |

|

New York |

$12,745 |

$3,900 |

$6,041 |

$774 |

$23,460 |

$18,102 |

|

North Carolina |

$5,439 |

$2,037 |

$668 |

$705 |

$8,850 |

$4,425 |

|

North Dakota |

$1,008 |

$148 |

$41 |

$53 |

$1,250 |

$1,129 |

|

Ohio |

$5,368 |

$2,270 |

$2,175 |

$844 |

$10,658 |

$5,329 |

|

Oklahoma |

$1,870 |

$769 |

$316 |

$238 |

$3,193 |

$1,597 |

|

Oregon |

$2,648 |

$819 |

$437 |

$248 |

$4,153 |

$3,400 |

|

Pennsylvania |

$7,291 |

$2,841 |

$2,335 |

$983 |

$13,450 |

$10,371 |

|

Rhode Island |

$1,131 |

$206 |

$273 |

$58 |

$1,668 |

$1,399 |

|

South Carolina |

$2,499 |

$1,000 |

$191 |

$435 |

$4,125 |

$3,312 |

|

South Dakota |

$974 |

$172 |

$38 |

$65 |

$1,250 |

$625 |

|

Tennessee |

$3,726 |

$1,326 |

$517 |

$438 |

$6,007 |

$3,004 |

|

Texas |

$15,814 |

$5,676 |

$3,377 |

$1,386 |

$26,254 |

$21,034 |

|

Utah |

$1,378 |

$623 |

$290 |

$187 |

$2,477 |

$1,239 |

|

Vermont |

$1,049 |

$121 |

$21 |

$59 |

$1,250 |

$625 |

|

Virginia |

$4,294 |

$1,658 |

$618 |

$634 |

$7,204 |

$5,749 |

|

Washington |

$4,428 |

$1,479 |

$770 |

$443 |

$7,120 |

$3,560 |

|

West Virginia |

$1,355 |

$348 |

$168 |

$162 |

$2,034 |

$1,017 |

|

Wisconsin |

$2,533 |

$1,131 |

$780 |

$412 |

$4,856 |

$2,428 |

|

Wyoming |

$1,068 |

$112 |

$21 |

$48 |

$1,250 |

$625 |

|

American Samoa |

$479 |

$11 |

$0 |

$5 |

$495 |

$487 |

|

Guam |

$554 |

$33 |

$0 |

$18 |

$604 |

$579 |

|

Northern Mariana Islands |

$482 |

$10 |

$0 |

$5 |

$498 |

$490 |

|

Puerto Rico |

$2,470 |

$620 |

$801 |

$125 |

$4,016 |

$3,243 |

|

Virgin Islands |

$515 |

$21 |

$0 |

$11 |

$547 |

$531 |

|

Tribal Governments |

$20,000 |

|

$20,000 |

$10,000 |

||

| Total | $219,800 | $65,100 | $45,570 | $19,530 | $350,000 | $235,417 |

*As noted earlier, non-entitlement units of local government will receive their allocations through their state governments. Disbursement information for these allocations is not yet available from Treasury, but we assume the same 50/50 tranche split as with the other local government assistance.

This blog post is a product of the COVID Money Tracker, an initiative of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget focused on identifying and tracking the disbursement of the trillions being poured into the economy to combat the crisis through legislative, administrative, and Federal Reserve actions.

1 Non-entitlement units of local government will receive their allocations through their state governments. Disbursement information for these allocations is not yet available from Treasury, but we assume the same 50:50 tranche split as with the other local government assistance.

2 The counterfactual trend growth calculation begins with the last full fiscal year before the public health emergency began and projects revenue into the future years with an annualized growth estimate. The annual growth rate used for the counterfactual trend is 4.1 percent per year or the recipient’s average revenue growth rate for the three full fiscal years before the public health emergency was declared, whichever is greater. The gap between this counterfactual revenue trend and actual revenue in a given year represents “lost revenue."