Reducing Build Back Better Inflation Risk

As we recently discussed, the House-passed Build Back Better Act is likely to be modestly inflationary over the next few years. Though we expect the effect to be small and temporary, there are risks of more significant effects given existing price pressures. Fortunately, adjustments to the legislation in the Senate could reduce or eliminate these inflation risks – chiefly by assuring the legislation is fully paid for without gimmicks or arbitrary expirations.

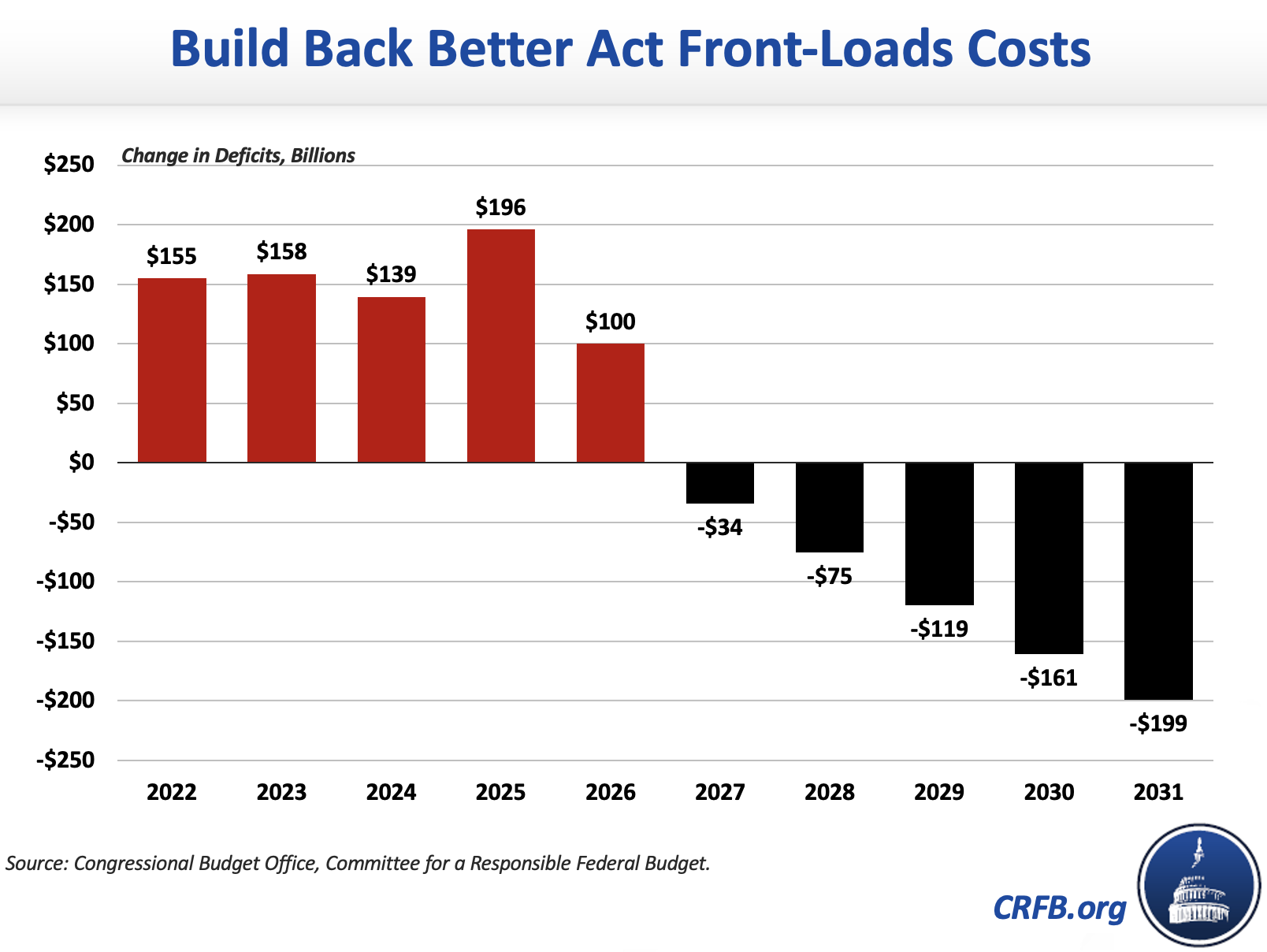

The most straightforward and important way to reduce Build Back Better’s inflationary pressures would be to replace its numerous temporary programs with fewer and/or smaller and better-targeted policies that are permanent and fully offset. Mostly because of the large temporary provisions in the bill, the Build Back Better Act would add over $150 billion to the deficit in the first nine months and $750 billion over the first five years.

In our Build Back Better for Less paper, we provide two illustrative frameworks that would not only be consistent with the overall Build Back Better agenda, but would also help to reduce inflationary pressures by making the bill fully offset and cutting back on some of the more excessive demand-side policies. Likewise, Ben Ritz of the Progressive Policy Institute has put forward his own suggestions for a package that would reduce the inflationary risk associated with Build Back Better. These alternative versions of the bill would be more fiscally responsible and more sustainable than the current House bill.

Short of these wholesale revisions, however, there are still several ways to reduce the potential inflationary impact of Build Back Better. Below, we discuss five such options.

- Remove the SALT Cap Increase. In addition to its many other flaws, the increase in the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap from $10,000 to $80,000 is likely one of the most inflationary parts of the House's Build Back Better Act. This is due mainly to its very high cost – $52 billion in the first nine months alone – and to a lesser degree its potential effect on housing prices. Removing the House's SALT cap increase would reduce the bill’s deficit impact by roughly a third in the first year and over the first five years. Even simply removing the retroactive SALT cap increase for 2021 – which will deliver a large, unexpected tax refund to high-income households in the Spring of 2022 – would reduce the near-term inflationary effects of Build Back Better.

- Pay Half the Child Tax Credit Monthly. For tax year 2022, the House's Build Back Better Act would increase the Child Tax Credit from $2,000 to $3,000 (and $3,600 for children under six), delivering the entire benefit in monthly installments. Instead, adopting President Biden’s proposal to deliver half the credit in monthly payments and half at tax time would reduce inflationary pressures over the next year without modifying the size of the credit. Following the White House proposal to better implement means testing and continue to limit the credit to children with a Social Security number could provide additional savings.

- Replace the Build Back Better Child Care Program. Though the Build Back Better child care proposal will reduce costs for many families, it may put upward pressure on prices in the economy – especially unsubsidized child care – through higher wages and increased demand for overall child care services. As written, the child care subsidies in the bill cost roughly $275 billion over a decade – enough to make the six-year universal pre-K program permanent, extend and reform the current child care tax credit, double the Child Care and Development Block Grant, and still reduce the overall cost of the Build Back Better Act.

- Fund Paid Leave with an Employer Payroll Tax. The House's Build Back Better Act provides four weeks of paid medical and family leave, funded from general revenue. Financing this $205 billion program through a payroll-tax-funded trust fund could slightly reduce the inflationary pressures of Build Back Better. A 0.4 percent employer-paid payroll tax, phased in by 0.1 percent per year starting in 2022, would be sufficient to cover the costs in full.

- Incorporate Further Health Savings. The House's Build Back Better Act proposes to substantially reduce prescription drug costs, but it otherwise does little to lower health care costs. Incorporating further health savings could reduce federal health spending while also lowering individual premiums and out-of-pocket costs. For example, policymakers could reduce excessive Medicare Advantage payments, equalize payments between hospitals and doctors, or reduce payments for post-acute care. These savings could be used to extend the bill’s Affordable Care Act expansions beyond 2025, scale back other offsets, or reduce the deficit impact of the bill.

Substantial changes are needed to make the Build Back Better Act fiscally responsible. In particular, eliminating arbitrary sunsets and instead fully funding programs over their time in effect would make the bill more responsible and reduce its potential inflationary pressures.

But even short of these important changes, the Build Back Better Act can be adjusted to remove some of the inflationary aspects of the package. Removing the SALT cap increase, adopting the President’s version of Child Tax Credit expansion, replacing the current child care subsidies, directly funding paid leave, and incorporating additional health savings could all help. Additional changes – such as phasing in offsets more rapidly and modifying various “Build America” and prevailing wage rules – could reduce those pressures further.

As written, we expect Build Back Better to modestly increase inflation. With inflation currently at a 30-year high, it is appropriate to be cautious and avoid adding further fuel to existing inflation pressures.

Read more options and analyses on our Reconciliation Resources page.