Look Out for Gimmicks!

The President is scheduled to release his budget tomorrow, which will detail his policy priorities for the coming decade. The budget typically details an array of new policy proposals and last year included a deficit reduction offer that reflected the end point of negotiations with House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) during the fiscal cliff showdown. Although the President is expected to abandon the deficit reduction offer framework, he should still put forward a budget that responsibly deals with our fiscal situation and puts debt on a downward path as a share of the economy. Our partners at Fix the Debt recently released What We Hope to See in the President's FY2015 Budget, which asks for the President to release a gimmick-free budget that puts debt on a downward path. Past budgets have used a variety of budget gimmicks to make future deficits look rosier than they actually were.

Here are several gimmicks the President should avoid:

1. Overly rosy economic assumptions

All legislation is measured by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which uses a standard set of economic assumptions about the next ten years to measure all legislation. Based on a consensus of economic forecasts, these assumptions show a very slow return to post-recession normalcy: real GDP growth averages just 2.5 percent per year, unemployment stays above 6 percent until 2017, and the economy does not reach full potential anytime within the next decade. In part due to these dour economic projections, CBO latest estimates show 10-year deficits $1.7 trillion larger than in last year's baseline assumptions.

The President's Budget is not required to follow the same economic assumptions that guide every other piece of legislation, but uses its own. By making assumptions about economic growth that are slightly rosier than CBO, the deficit can look much smaller than CBO projects. For instance, if annual real growth averaged just 0.2 percentage points higher than in the baseline, projected debt in 2024 would be more than $600 billion dollars smaller. OMB can disagree with CBO on its forecast of the economy, but it should not use unrealistically optimistic assumptions to make budget numbers look better.

2. Unintended expiration assumptions

The President supports a number of provisions that are currently either expired or soon to expire. For instance, the tax credit for business research expenses, which he mentioned in last month's State of the Union address, expired at the end of 2013. He'd also avoid the nearly 25 percent cut to Medicare physician payments under the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, currently scheduled to take effect at the end of March. However, both of these initiatives would be expensive – $66 billion for the tax credit and $115 billion for SGR through 2024. If the President supports these programs, the budget should include their costs. It would be a gimmick for the budget to neglect to mention them or only pay for one year of costs when the programs will continue beyond one year.

3. Magic asterisks

The budget should avoid any "magic asterisks" that assume savings will materialize without specifying their source. This has happened in past budgets -- for example, assuming "bipartisan financing" of an infrastructure proposal without specifying a financing mechanism -- although last year's budget did not do this. Every savings line in the budget should have specific policies attached to it.

4. Phantom savings

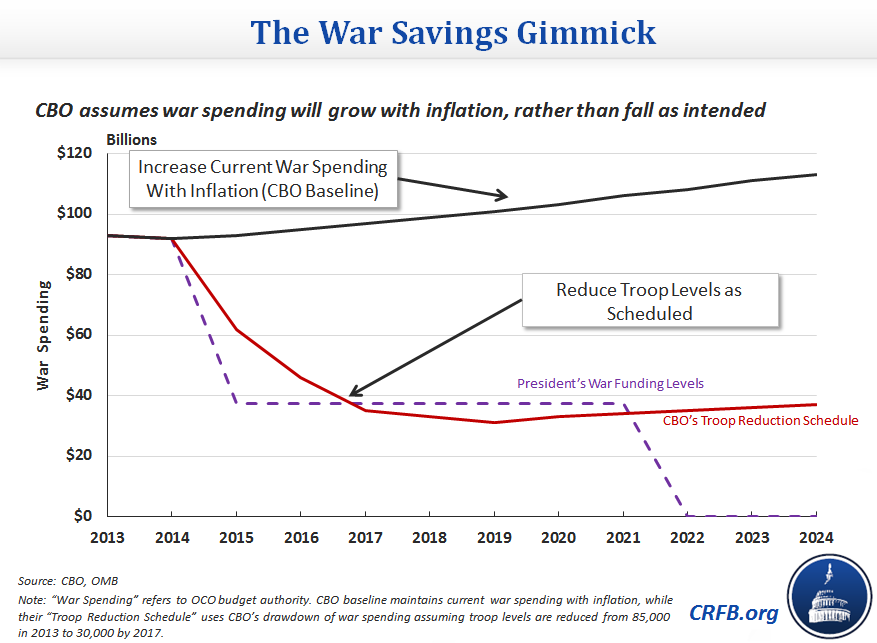

The budget also should not assume "phantom savings," counting savings that are scheduled to or have already materialized. The most popular version of this gimmick is the war savings gimmick. Under current budget convention, uncapped discretionary spending, like war spending, is assumed to grow with inflation in the CBO baseline. However, actual costs will almost certainly decline as the drawdown in Afghanistan continues, resulting in almost $600 billion in savings compared to the baseline. These savings are already scheduled to occur as our engagement draws down, and the budget should not rely on them to offset new spending or tax cuts.

The President's budget last year, as shown below, envisioned war spending levels being reduced dramatically, eventually zeroing out by 2022.

5. Manipulating the baseline

Another place that costs can often be hidden is inside the baseline. For instance, last year's baseline included the permanent extension of refundable tax credit expansions enacted in the 2009 stimulus and permanent avoidance of Medicare physician payment cuts. By assuming a policy as part of the baseline, the budget effectively hides the cost of a policy, although last year's budget had enough savings to offset those policies. Although this is less of a concern now that there are fewer expiring provisions with less of a budgetary effect, there is still a danger of deficit-financing extensions of current policies.

Hopefully, the President's budget will be free of these gimmicks and put debt on a downward path as a share of the economy.