IRS Loses $400 Billion Per Year in Unpaid Taxes

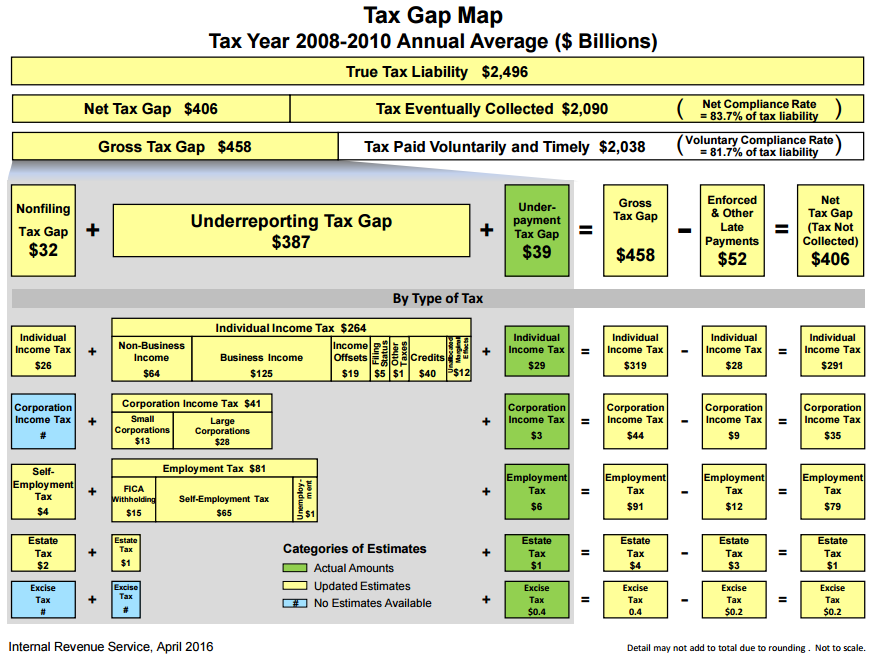

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recently released new estimates of the “tax gap” – the amount of taxes owed that go uncollected. They reveal that only 84 percent of the money owed in taxes is collected each year, which resulted in a "net tax gap" of $406 billion per year on average between 2008 and 2010. That amount is a combined $458 billion not voluntarily paid and another $52 billion collected after the IRS contacted those who were delinquent. The net tax gap of $406 billion is about 2.8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which would be equivalent to $6.5 trillion over the next decade.

Most of the tax gap – $387 billion, or 84 percent of the gross amount – comes from taxpayers underreporting income. Approximately half of the net tax gap ($203 billion) comes from underreported pass-through business income, small corporation income, and the self-employment payroll tax.

In addition to underreporting, underpayments accounted for $39 billion of the tax gap and those that didn't file any returns accounted for $32 billion. The vast majority of underpayments and nonfilers ($55 billion) came from individual income taxes, though the IRS does not break out exactly where they came from.

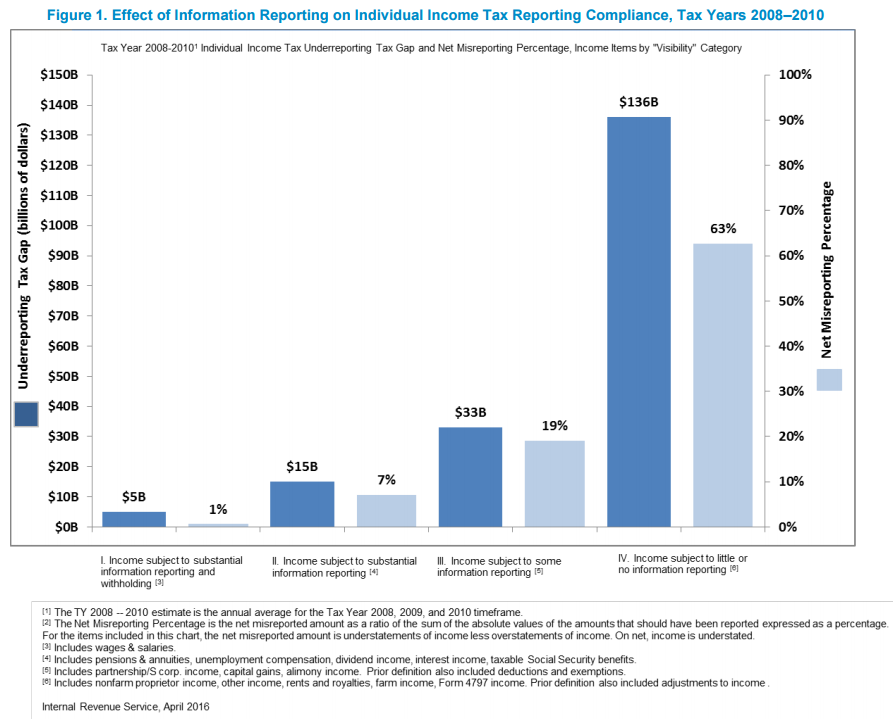

It makes a big difference whether tax is withheld or if income is at least reported to the IRS. When income is neither reported or withheld, 63 percent of that income was misreported. When income was withheld, the misreporting rate drops to 1 percent.

The net tax gap is 1.8 percentage points higher than the last estimate for 2006, though that higher figure is due to improved estimating methodology, not a drop in compliance.

Since 2008-2010 were very low tax collection years, the tax gap has likely grown, making it an even larger potential pot of money (unless tax compliance rates have increased significantly). Policymakers should do as much as they can to ensure everyone (and every business) is paying the taxes they owe.

However, while everyone can agree in theory that the tax gap should be reduced, some amount of tax gap is inevitable. Policies to reduce the tax gap are not necessarily a free lunch. They could require giving the IRS more power and may increase administrative or reporting costs for the IRS, businesses, financial institutions, or individuals. Policymakers will need to strike a balance between reducing the tax gap and high compliance costs.

For instance, our 2015 PREP Plan to pay for tax extenders found nearly $100 billion in offsets over ten years, almost entirely from improving tax compliance and closing loopholes that are inconsistent with the spirit of the tax law (the revenue lost from loopholes, though, would not show up in the tax gap numbers). Most of the compliance measures we originally proposed in 2014 have been enacted since then.

President Obama also introduced tax gap policies that would save about $55 billion over a decade, an estimated $40 billion of which would result from increased funding for the IRS, allowing for more audits and improving tax compliance. In addition, a provision in the Affordable Care Act that was repealed in 2011 that would have expanded reporting for payments to small businesses would have raised $22 billion over ten years.

IRS funding has decreased by $900 million (paywall) since 2010, while the number of taxpayers has increased by 10 million. While reducing the tax gap is necessary, the measures put forward would only tackle a small fraction: less than $10 billion per year out of a gap that exceeds $400 billion.

A more significant way to reduce the tax gap is to reform the tax code to make it simpler and to reduce the opportunities to hide and underreport income in the first place. Tax reform could raise revenue and have the added benefit of reducing the tax gap and easing the IRS's administrative burden.