How the Fiscal Cliff Will Affect Taxpayers

UPDATE: Tax Policy Center also has a video in which TPC director Donald Marron walks through their findings.

It is no secret that the fiscal cliff would be damaging to the economy. Many private forecasters and the Congressional Budget Office have attempted to quantify how much it would hurt growth and increase unemployment. In that vein, a Tax Policy Center report released today, “Toppling Off the Fiscal Cliff: Whose Taxes Rise and How Much,” tackles the question of who would be affected and how much taxes would increase for each income group.

In the report, TPC finds that 90 percent of Americans will see their taxes go up starting on January 1. The average tax increase would be $3,500, and the typical middle-income taxpayer would see his or her tax bill go up by $2,500. The fiscal cliff’s broad-based effect stems from the variety of temporary tax measures ending, a laundry list that includes provisions that largely affect the wealthy (expiring tax cuts for capital gains, dividends, and estates; the expiration of the Alternative Minimum Tax patch; the introduction of the new Affordable Care Act (ACA) taxes) and those that have a greater effect on the bottom of the income distribution (the expiration of the American Opportunity Credit and the reductions in the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit).

The largest increases that would result from careening off the fiscal cliff would result from the expiration of two different policies: the expiration of the 2001/2003 tax cuts, and the end of the payroll tax cut that originated in the 2010 tax deal between President Obama and Congress. Though the expiration of the 2001/2003 tax cuts would be a progressive change (rate increases would go from 0.5 percent on the lowest income quintile to 2.9 percent on the highest), the end of the payroll tax reduction -- which, according to The New York Times, may be allowed to happen -- would be mildly regressive at the high end (an increase of 1.1 percent for the bottom quintile, but 0.8 percent for the top quintile).

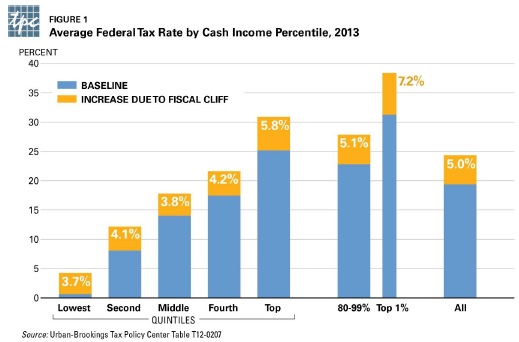

The result of all these changes is a somewhat progressive tax increase. Tax rates for the bottom and top quintiles would rise by 3.7 and 5.8 percentage points, respectively, with the middle quintiles facing higher rates in between those amounts. The top 1 percent would face an average tax rate increase of 7.2 percent, mostly due to the 2001/2003 upper-income tax cuts and the ACA taxes.

Even if the cliff is somewhat progressive, there are very few people who would not be affected by the fiscal cliff’s tax changes. And even among those who aren't--generally concentrated in the lowest quintile and likely including many elderly taxpayers--the cliff may affect them in other ways--for example, through the expiration of extended unemployment benefits or the drastic cut to Medicare physician payments.

While the fiscal cliff's large immediate tax increases (and sharp across-the-board spending cuts) would be harmful to the economy, we will not be able to get sufficient deficit reduction without tax increases being part of the solution. But there is a better way to do it than a slew of rate increases. Bipartisan plans such as Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin showed that pro-growth tax reform could increase or at least maintain progressivity and raise revenue. That would be much a preferable way to go than the cliff.