Growth and Deficit Reduction Are Not Incompatible

Yesterday in an interview on CNBC's Squawkbox, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers chimed in again on his views that boosting economic growth should be a more important priority than making long-term budget reforms. As CRFB said late last year in response to one of his op-eds, Dr. Summers's arguments seem to feed the false notion that long-term debt reduction and a growth strategy somehow conflict, when in reality they are one and the same. In addition, Dr. Summers continues to mistakenly believe that growth alone can solve our budget problems.

Specifically, Dr. Summers states that:

"If the economy grows fast, the long-term budget will be fine. If the economy does not grow fast, we can do one measure or another, [but] we're still going to have to have rapid debt accumulation...The most important determinant of opportunity for my children and your children is how rapidly we grow this economy. I hope we move to a focus on more rapid growth."

Let's address these and a few other claims he has made.

Can Economic Growth Solve the Debt Problem?

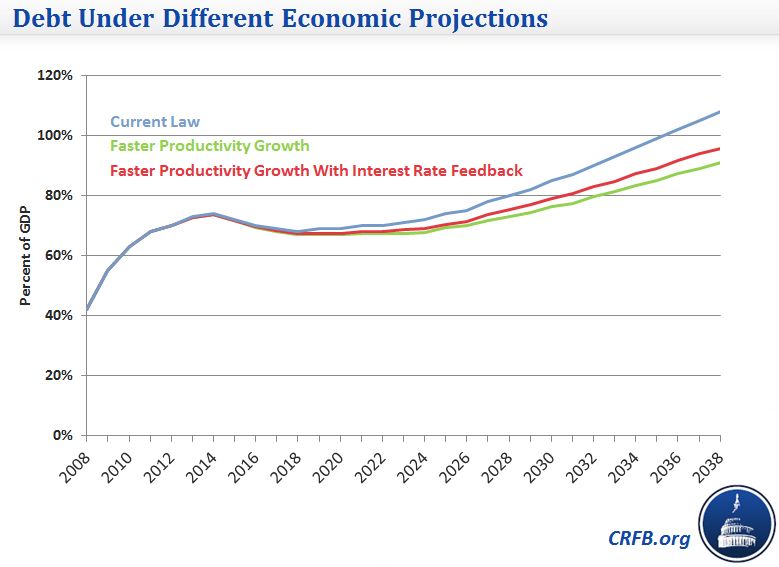

First of all, we completely agree with Dr. Summers that strong growth is imperative to successfully bringing the debt down to healthy levels. However, economic growth alone cannot solve our debt challenge. When we analyzed a slight increase in annual growth rates along the lines of what Summers suggested would solve the long-term budget problem -- about a 0.2 percentage point increase in real GDP growth from a 15 percent increase in productivity -- we found it would not, in fact, reduce the debt as a share of the economy. And even according to his estimates, slightly faster economic growth alone would still take decades and decades just to bring the debt down to where it is now—an already elevated level.

Faster economic growth helps to bring debt levels down by generating more revenue, decreasing short-term spending on some safety net programs, and increasing the denominator in debt-to-GDP calculations. However, higher growth has also been linked to increased health care spending and would also drive up retirement spending as wages rose, moderating some of the long-term budget gains from faster growth.

Rising long-term debt levels should continue to prompt serious concern. The non-partisan CBO makes it very clear that rising debt levels will hold back economic growth and higher incomes down the road, in addition to the interest rate risk and budget flexibility problems that rising debt creates.

But Wait, What about The Risk of "Secular Stagnation"?

Even if stronger growth could solve the problem, Dr. Summers has also been advancing the idea that the normal economy may have become incapable of creating sustained periods of full employment and financial stability, an idea known as secular stagnation. A recent paper from an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimates that in the wake of economic downturn, potential GDP growth in the business sector may only be 2.1 percent—notably lower than the CBO's projection of 2.6 percent for the non-farm business sector and 2.2 percent for the economy at large. Our estimates, based on CBO data, show that slower growth of 0.5 percentage points a year would push the debt up from nearly 110 percent of GDP in 2040 under current law to nearly 140 percent. Even a 0.2 percentage point growth reduction each year would yield notably higher debt levels -- exceeding 120 percent of GDP in 2040.

Thus, it is curious that Dr. Summers has been arguing that all we need is slightly stronger growth, when in other forums the ideas he's advancing suggest it might be tough to achieve current growth rates, let alone even stronger ones.

To be sure, Dr. Summers argues for policies he believes can help get us out of secular stagnation -- namely a massive new set of infrastructure projects. Certainly, well-targeted public investments can improve short-term and longer-term growth prospects. But it would be quite ambitious to think we can make enough productive investments to get out of secular stagnation and further increase productivity by about 15 percent each year going forward. This is especially true given that an effort of this size would dramatically increase the national debt due to its cost, which would threaten to both slow long-term growth rates and, more directly, work against debt reduction efforts. For these reason, it is unlikely any amount of new investment would help with long-term debt levels unless accompanied by other reforms.

A Comprehensive Strategy

A better approach for policymakers would be to pursue short-term and long-term growth strategies that are either a part of a long-term debt reduction package -- including reforms to health care programs, retirement programs, and the tax code -- or are implemented in tandem with it.

A comprehensive growth strategy could support increased spending, temporary tax provisions, or a combination of the two in the short term -- such as renewing emergency unemployment benefits on the low end and large-scale investment projects on the high-end. Policymakers could focus more on productive investments in infrastructure, education, and research and development. On the fiscal reform side, lawmakers would have to look to comprehensive tax reforms to reduce economic distortions and enhance competitiveness and investment. At the same time, entitlement reforms would be critical to encourage more savings, more work, and constrained growth in national health care costs. The critical piece in all this will be putting the debt on a clear downward path relative to the economy.

Pursuing regulatory reforms, immigration reform, trade-related issues, and other components of a growth strategy could also be in the picture. In the end, a comprehensive growth and deficit reduction strategy could also reduce uncertainty and improve confidence in the future course of the economy and what policy steps lawmakers will take.

Debt reduction and economic growth over the long term will go hand-in-hand.