Getting the Facts Right on Social Security

Note: This piece was originally posted on the Angry Bear blog.

The late Senator Moynihan once said that “everyone is entitled to his own opinions but not to his own facts.” In response to our piece, “Setting the Record Straight on Social Security,” Dale Coberly calls both our facts and our opinions “lies.” In his treatise, Coberly adds several important ideas to the discussion, but much of his piece misrepresents CRFB’s views, misattributes our motives, and asserts claims which are simply not based in fact.

We pride ourselves on our fact-based, non-partisan analysis, which Coberly calls into question in his piece. Below, we review and debunk many of his claims:

Claim #1: CRFB advocates a cuts-only solution to Social Security.

FALSE. Coberly claims that “CRFB would like you to believe the only solution is to cut benefits,” that we only “pretend to be open to revenue enhancements,” and that our Social Security Reformer “is rigged so you can’t give the correct answer [of gradually raising the payroll tax rate].”

This claim is nonsense. The blog clearly states that a reform “could increase revenue coming into the system, slow the growth of benefits being paid out, and even offer some targeted benefit enhancements to those who truly need them” – and we have said this consistently over the years. In fact, our do-it-your-self Reformer offers users a number of different revenue options to choose from and lets users increase the payroll tax rate by whatever amount they wish (it’s true we don’t have the functionality to adjust the phase-in rate of tax or benefit changes, which we hope to include in a future version). In addition, the two plans we repeatedly cite in our blog – Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin – both propose a mix of revenue and benefit changes, and a separate plan developed by CRFB President Maya MacGuineas along with Jeff Liebman and Andrew Samwick relied heavily on revenues as part of a solution, which also included targeted benefit enhancements.

Claim #2: CRFB wants to turn Social Security into a welfare program.

FALSE. Colberly claims that our goal is to “turn Social Security into a welfare program by means testing” and that “CRFB would tax you to pay for benefits that only ‘the deserving poor’ would receive after careful examination to be sure they were poor enough to ‘deserve’ welfare.”

This claim also has no basis in fact. CRFB takes no position on whether benefits should be means-tested and nowhere in our entire blog do we propose means-testing benefits in any form. The plans we reference – Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin – do make the benefit formula more progressive, but they still maintain a link between contributions and benefits received.

In fact, our only mention of the concept is to warn that those who support eliminating the cap on income subject to Social Security payroll taxes must make a choice between offering huge benefit increases to the rich and means-testing benefits for that group; this may be an unattractive choice for progressive supporters of social insurance.

Claim #3: Social Security’s Finances Could be Solved by Raising the Payroll Tax 0.1 Percentage Points Per Year Until It’s Increased by 2.7 Percent

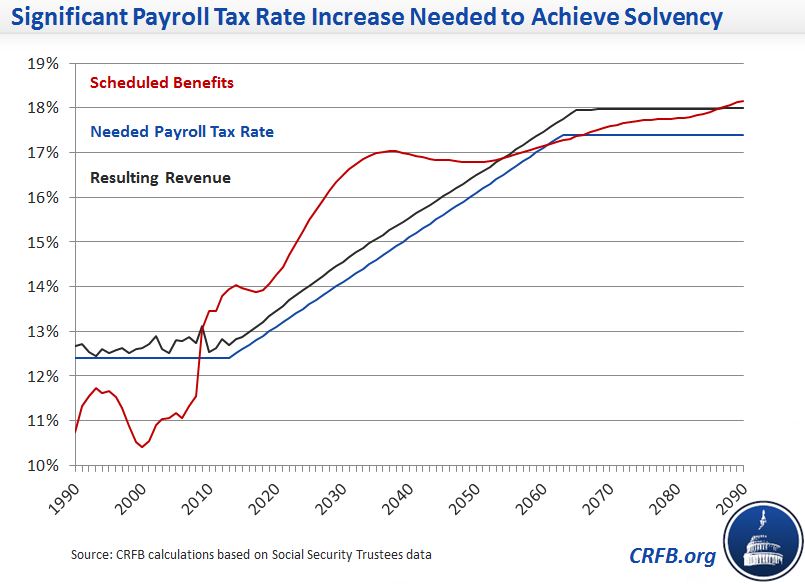

HALF TRUE. Coberly argues that we need not worry about Social Security’s finances because raising the payroll tax rate by only 0.1 percent per year would make the program solvent, until it’s increased by 2.7 percent. It’s true that solvency can be maintained by increasing the payroll tax by 0.1 percentage points a year, but the ultimate increase would have to be far in excess of 2.7 points percentage points.

Indeed, to make Social Security solvent for 75 years, the payroll tax would have to be raised by 0.1 percentage points per year for the next 40+ years – by over 4 percentage points in total. In other words, the payroll tax rate would ultimately have to be increased by one-third. And achieving sustainable solvency would require an additional decade of increasing the payroll tax rate, ultimately raising the payroll tax rate by 5 percentage points – from 12.4 to 17.4 percent. (As we explain in claim #4, the reason this increase is so much higher than Coberly claims is related to the real cost of waiting to implement savings.)This increase, importantly, would apply to all workers, including the very poor. Increasing the payroll tax is a legitimate policy option that should be part of the debate, but many progressives would be concerned with large tax increases on low-income workers in order to finance the rapid continued growth of retirement benefits, a good share of which goes to the wealthiest seniors.

Claim #4: There is No Cost to Waiting to Reform Social Security

FALSE. Coberly calls our claim that delaying action on Social Security has costs “a lie,” positing that “waiting will not lead to increased costs or deeper cuts. It would [only] lead to a steeper rate of increase.”

Coberly is mistaken. As Doug Elmendorf, director of the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office recently stated in testimony before Congress “there is certainly a cost to waiting….the longer one waits to make changes, the larger the changes need to be and the more abruptly they would need to take effect.”

Not only does it mean any tax increases or benefit cuts will be steeper, but it literally means they will need to be bigger in magnitude. This is true for at least two reasons. First, waiting will mean that there are fewer total people to share in the tax increases or spending cuts – that means more increases/cuts per person. Secondly, the longer we wait, the less money is in the trust fund and the less interest it will generate.

Although Coberly suggests that the actuarial deficit of 2.7% of payroll over the next seventy five years could be closed by gradually implementing a 2.7% increase in the payroll tax over twenty plus years, the 2013 Social Security Trustees report clearly states that in order to make Social Security solvent for 75 years, “revenues would have to increase by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent payroll tax increase of 2.66 percentage points.” (emphasis added) In a paper on this topic, we showed that what could be solved with a 16.5 percent across-the-board benefit cut today would require a 19 percent cut if we wait a decade and a 23 percent cut if we wait two decades. Similarly, the 2.7 percentage point increase in the payroll tax needed to close the 75-year gap today would be 3.3 points if we waited until 2023 and 4.2 if we waited until 2033.

Claim #5: Social Security Does Not Really Run a Deficit

MOSTLY FALSE. Coberly calls our claim that benefits exceed payroll tax revenue “a clever lie” because we do not (but should) count assets from the trust fund as revenue. Specifically, he argues that “the revenue from previous payroll taxes … were saved exactly in anticipation of the higher costs that Social Security is facing today. It’s as if you saved up money in advance to pay for your Christmas shopping, and then, when December comes, the CRFB runs around telling your neighbors you are bankrupt because you are ‘spending more than you are taking in.”

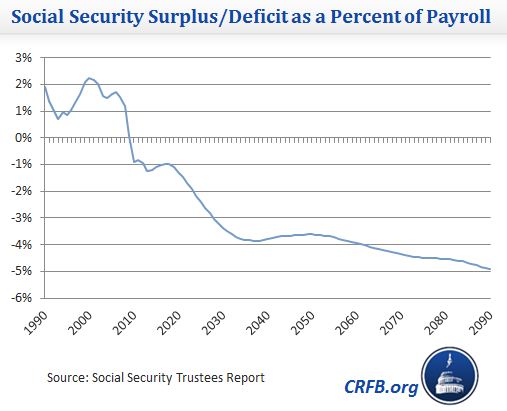

Here, Coberly confuses the flow of funds with the stock of funds. If an individual, business, or government spends more than they take in, they are running a deficit. If an individual, business, or government spends more than they have, they are in debt. We never claimed Social Security was in debt, but it is running a large cash deficit – totaling about $75 billion in 2013 alone. Notably, Social Security is still running a small surplus when interest is included, but even that surplus is expected to disappear in a few years; and most analysts prefer to focus on cash flow.

Don’t believe us? Ask Social Security’s own Trustees who say that “for both the OASDI and HI [Medicare] programs, the Trustees project annual deficits for almost every year of the projection period” or the Congressional Budget Office who explains that “in 2012, outlays exceeded noninterest income by about 7 percent, and CBO projects that the gap will average about 12 percent of tax revenues over the next decade.”

As for the suggestion that we’ve saved money for the current deficits, Coberly’s metaphor simply doesn’t match since (unlike Christmas) these deficits are not a temporary event. The more comparable situation would be if an individual saved money every year of his 20s and then decided to spend more than he earned for the remainder of his life. In his 30s, he might be able to rely on past savings to make up the difference, but that money will dry up soon. In the case of Social Security, that will likely happen in the early 2030s; and when the trust fund runs out, our revenue will only cover about three-quarters of our spending.

Claim #6: Social Security’s Deficit is Due to the Payroll Tax Holiday CRFB Advocated

FALSE. Coberly states that, “Another reason CRFB can say the cost of benefits are ‘well in excess of revenue from payroll taxes’ is that recently the friends of CRFB persuaded the politicians to ‘cut payroll taxes’ to provide a stimulus to the economy.”

In fact, the payroll tax holiday has nothing to do with Social Security’s trust fund or deficit. The revenue loss was made up for with a general revenue transfer that is not included in the $75 billion cash deficit we cite. The Office of Management and Budget noted that “general fund transfers…substitute[d] for the payroll tax revenue lost by the payroll tax reduction, so that the balances of the Social Security trust funds are the same as they would have been in the absence of the legislation. As a result, the payroll tax reduction did not impact the long-term solvency of the trust funds.”

Moreover, CRFB did not advocate for or against a payroll tax holiday. It’s true we do have many friends that supported the payroll tax holiday (along with some progressive organizations who disagree with us on Social Security), but we also have many friends that opposed the payroll tax holiday. The assertion that CRFB advocated for a payroll tax holiday as part of a plot to undermine Social Security has no basis in fact.

Claim #7: Social Security Does Not Add to the Budget Deficit

MOSTLY FALSE. Coberly claims that CRFB is trying to confuse readers by suggesting that Social Security is currently adding to the federal budget deficit. Yet if we are trying to confuse the reader, so too is the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office and the President’s own Office of Management and Budget.

As we’ve explained before, there are two ways to look at Social Security – as its own isolated program and part of the broader budget. There are also at least two ways to measure the federal budget deficit – by looking at the “on-budget deficit” and by looking at the “unified budget deficit.” Social Security does not add to the on-budget deficit. But most economists, analysts, reporters, and politicians prefer to look at the unified deficit. And here, Social Security is – net of its payroll taxes – contributing to the deficit.

Note that this unified view has been used to describe the deficit reduction generated in both the Affordable Care Act and the Senate-passed immigration bill.

Claim #8: Social Security is a way for workers to save their own money.

MOSTLY FALSE. In attacking the idea of means-testing, Coberly asserts that Social Security “is a way for workers to save their own money, protected from inflation and market losses, and insured against personal misfortune. That is, it is protected by the government, but not paid for by the government.”

This assertion shows a misunderstanding of how the Social Security program works. Social Security is a government program in which the government collects payroll taxes and then pays benefits to seniors, disabled workers, and their dependents. Some view Social Security as just another government program, others view it as a publicly-administered (and mandated) social insurance policy, but no serious analysts view Social Security as a true savings program.

For one, payroll tax contributions are not set aside in a savings account or even a pooled fund of savings; they are used to pay current benefits. Additionally, benefits are not determined based on payroll tax contributions – they are determined by applying a progressive formula to wage history that assures higher lifetime earners receive more in nominal benefits than lower earners, but less as a share of their salary. It’s true that Social Security does have a few things in common with a system of forced savings – it reduces the amount a worker can spend now and provides more resources later – but the program is not a “way for workers to save their own money.”

Claim #9: The question of whether past surpluses have been saved in an economic sense is an irrelevant issue invented by CRFB to justify benefit cuts.

FALSE. Coberly suggests that “CRFB would have you believe the United States of America cannot pay back the money it borrowed because it ‘did not save’ that money ‘in an economic sense.’”

Actually, we specifically explain that the budgetary impact of Social Security’s shortfalls exist “regardless of whether past surpluses were saved in an economic sense or not,” and none of our critique focuses on that question. Nor do we suggest that the Treasury cannot pay back the money it borrowed from the Social Security system. We simply pointed out that the government will need to borrow money from the private sector to cover Social Security’s cash shortfalls.

Although barely mentioned in our blog, it is widely accepted that the existence of trust fund balances has no bearing on the ability of the government to pay benefits unless the past surpluses were saved in an economic sense. The Analytical Perspectives volume of President Obama’s Fiscal Year 2014 budget stated, “The existence of large trust fund balances, while representing a legal claim on the Treasury, does not, by itself, determine the Government’s ability to pay benefits. From an economic standpoint, the Government is able to prefund benefits only by increasing savings and investments in the economy as a whole.”

The question of whether Social Security’s surpluses have led to an increase in savings in the rest of government is a hotly debated one in the economic community. If it has, it could be argued that the government is better-equipped than it would otherwise have been to pay back Social Security benefits. If it hasn’t, it means that the Social Security program is ultimately leading to higher net borrowing than would otherwise be the case. But either way, in the here and now, the federal government has to borrow more on the open-market to finance Social Security deficits than if the program were in balance.

Claim #10: CRFB Advocates Cuts to Means-Tested Programs and Doesn’t Care About Investing in Future Generations

FALSE. Coberly calls our claim that raising revenue for Social Security might leave less money for investments and younger generations disingenuous, suggesting that “these are the people cutting food stamps (for children) in order to fund investments … in the next dot.com bubble or housing finance fraud.”

This is false. The deficit reduction plans we cite in our piece – Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin – specifically take most low-income support programs off the table. Neither includes reductions to food stamps, welfare, SSI, or related programs.

It is irresponsible to look at Social Security in isolation without considering the impact that meeting its financial obligations will have on our ability to meet other needs. The Congressional Budget Office and other non-partisan analysts have made warnings similar to ours that the rapid growth in spending on entitlement programs and interest on our debt will squeeze out other government spending. Much of our concern about the growth of entitlement programs and deficits is motivated by our view that unchecked growth of entitlement spending will harm the economy and the living standards of future generations by squeezing out spending on programs that invest in the future.

And the claim that Social Security competes with other programs is not just theoretical. The recent budgetary discussions show just how concrete the competition is. Both sides entertained adopting the so-called Chained CPI, which would have slowed Social Security cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) and other inflation updates in the budget and tax code to the actual rate of inflation, in order to replace part of sequestration. Because this and other changes were not adopted, most of sequestration is being allowed to take place, leading to large reductions in programs like Head Start, health and scientific research, low-income housing assistance, primary education, and job training.

Despite Coberly’s efforts to dismiss our warnings, the reality is that numerous non-partisan analyses confirm that Social Security is facing serious financial problems that adversely affect both the ability of the program to meet future obligations and the federal budget as a whole. We can and should have a vigorous debate about the best mix of policies to address this problem. But that debate should be based on an honest recognition of the facts regarding Social Security’s financial condition.